There are many things that God put in this world which require an acquired taste to enjoy. Coffee, beer, wine, and dark chocolate all come to mind.

If we get past the things that only touch our tongues, I would also add British humor. Or should I say, humour?

Somewhere along the way, this is a taste I’ve acquired. My first exposure very well could have been Monty Python sketches. They were absurd, and I found them extremely amusing.

Around the same time that Monty Python was active, the Smothers Brothers had a show, Steve Martin was just getting started, and the first season of SNL was only a few years out. Clearly there was something in the air as the comedy world went into the 1970's.

(I’m not enough of a student of comedy to say how this came to be or how they relate to one another. At least, not with any assurance. But I can say with some assurance that God has a sense of humor. Because if His image-bearers do, then it only follows that He does too. Which then means that holy humor is not only possible, but greatest. Unfortunately, this is an idea that's foreign to us. But that's another blog post.)

While comedy has changed a lot since the late 1960’s (and not necessarily for the better), it’s that acquired taste for absurd, dryly-delivered sketch comedy that’s made me appreciate skits like Two Guys on a Scooter by Studio C or Washington’s Dream with Nate Bargatze on SNL.

Neither of these are British, so obviously they can’t be British humor. But they’re also not British because their flavor profile isn’t quite right. British humor is distinct, and its flavor has kept calm and carried on since before Monty Python came about. I'm sure there are many better than me who can wax eloquent on the subject. They already have on its Wikipedia page. Suffice it to say that, “British humour carries a strong element of satire aimed at the absurdity of everyday life.”

But honestly, reading about it just doesn’t compare to discovering it for yourself. To that end, you can get a feel for this flavor in Tim FizHigham’s story All at Sea. He's an Englishman who set out to row the English channel in a bathtub. (If you haven’t listened to this, you really should. It’s a masterclass. Give the title a double-click to make it start playing.) Here's what he shares to close:

If we get past the things that only touch our tongues, I would also add British humor. Or should I say, humour?

Somewhere along the way, this is a taste I’ve acquired. My first exposure very well could have been Monty Python sketches. They were absurd, and I found them extremely amusing.

Around the same time that Monty Python was active, the Smothers Brothers had a show, Steve Martin was just getting started, and the first season of SNL was only a few years out. Clearly there was something in the air as the comedy world went into the 1970's.

(I’m not enough of a student of comedy to say how this came to be or how they relate to one another. At least, not with any assurance. But I can say with some assurance that God has a sense of humor. Because if His image-bearers do, then it only follows that He does too. Which then means that holy humor is not only possible, but greatest. Unfortunately, this is an idea that's foreign to us. But that's another blog post.)

While comedy has changed a lot since the late 1960’s (and not necessarily for the better), it’s that acquired taste for absurd, dryly-delivered sketch comedy that’s made me appreciate skits like Two Guys on a Scooter by Studio C or Washington’s Dream with Nate Bargatze on SNL.

Neither of these are British, so obviously they can’t be British humor. But they’re also not British because their flavor profile isn’t quite right. British humor is distinct, and its flavor has kept calm and carried on since before Monty Python came about. I'm sure there are many better than me who can wax eloquent on the subject. They already have on its Wikipedia page. Suffice it to say that, “British humour carries a strong element of satire aimed at the absurdity of everyday life.”

But honestly, reading about it just doesn’t compare to discovering it for yourself. To that end, you can get a feel for this flavor in Tim FizHigham’s story All at Sea. He's an Englishman who set out to row the English channel in a bathtub. (If you haven’t listened to this, you really should. It’s a masterclass. Give the title a double-click to make it start playing.) Here's what he shares to close:

Great Britain is a land where you can turn to the Great British public, look them directly in the eye and go, "I'm going to do something really quite hard." You can say, "I'm going to run up Kilimanjaro, or I'm going to climb Everest."

And the Great British public will look you in the eye and they will go, "Well it's not that hard."

Or you can look them in the eye and go, "I'm going to do something really quite hard like run up Kilimanjaro or climb Everest or row the English Channel dressed as a dolphin or carrying a fridge or wrestling a weasel."

And the Great British public will look you directly in the eye and go, "This man's a hero. Get right behind him ladies and gentlemen. Someone get the prime minister on the phone."

I don't know what it says about Britain as a nation, but I've broken my entire body to prove it to be true.

While this quote doesn't directly describe to British humor, it does give a good sense of the people who have it.

A Litmus Test

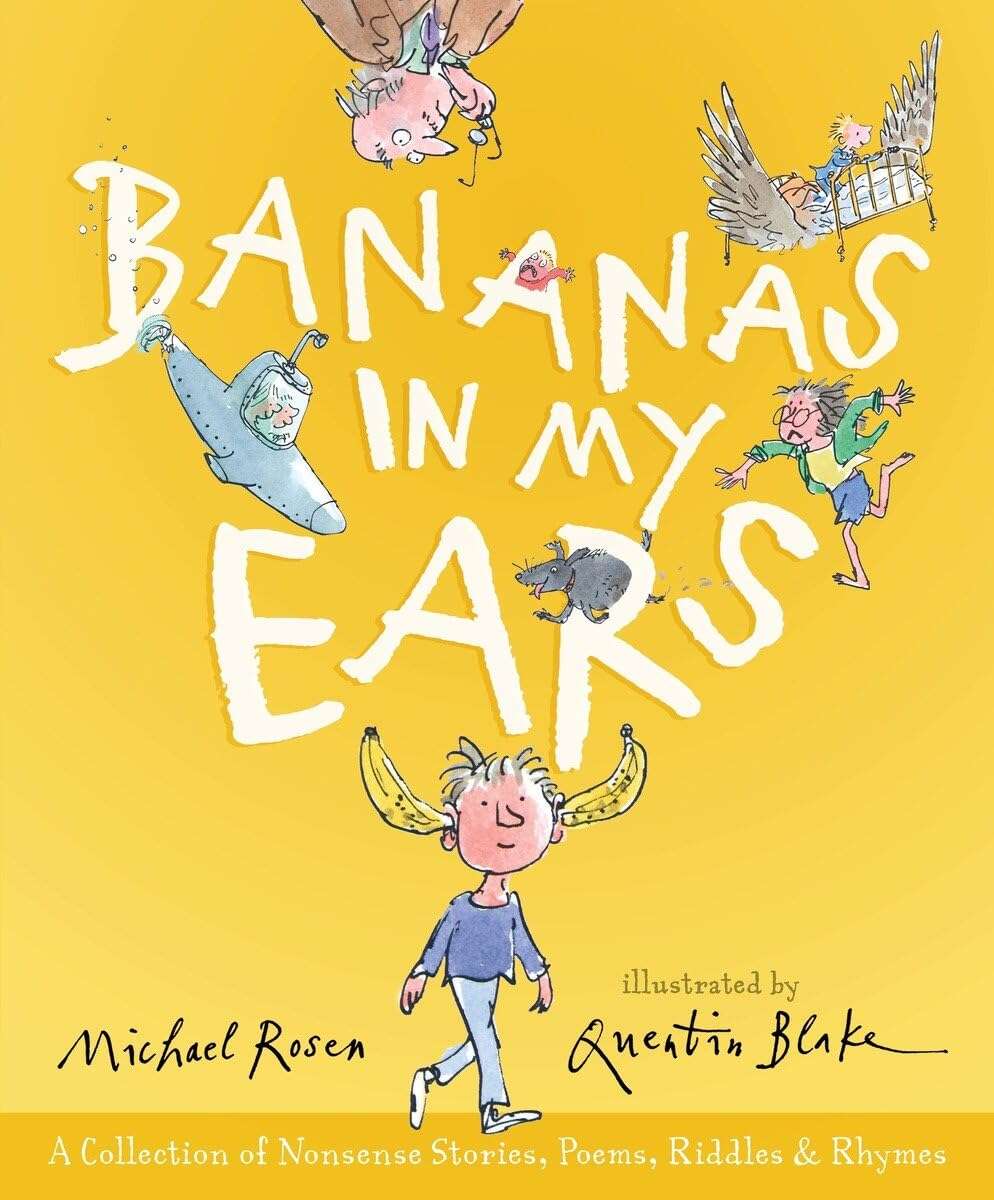

I found the true litmus test for British humor in a children’s book I checked out at random from the library: Bananas in My Ears by Michael Rosen. (This book prompted this entire blog post, actually.)

But I didn’t know I was about to get tested when I brought it home from the library. I grabbed it because Quentin Blake’s illustrations appealed to me. It looked fun! (I do judge books by their covers in the children's section of the library, and I am not apologetic about it).

So when I sat down to read it with Martha, I was surprised. How could anyone read this? It was utter nonsense! (To be fair, the subtitle “A Collection of Nonsense Stories, Poems, Riddles & Rhymes” warns of this.) My error was that I failed to remember that nonsense appeals to children—they often think in nonsensical ways. ("Creative" might be another word for it.) But nonsense written for American children is one thing—nonsense written for British children is a bit more of a reach from this side of the pond. (Still, I tip my hat to Michael Rosen and Quentin Blake, both of whom are Englishmen. They really got it right in this book, so much of it sounds like it was simply transcribed from the mouths of children.)

I admit, I almost gave up. I don’t know why we kept reading. Maybe it was the illustrations, maybe it was a desire to get some sort of return on my investment, maybe it was a sense of discovery. For whatever reason, we pressed on. I’m glad we did. The more we read, the more we liked it. The more we liked it, the more we wanted to read.

Martha and I ended up reading the entire book in one sitting—a real feat! It was an amazing and special hour of shared chuckles and laughs. Over the following week we revisited it again and again, often reading aloud our favorites to the rest of the family. By the end of it, our family had several new inside jokes—a shared language for us to enjoy.

It wasn't until I shared this book with friends that I realized that it was a taste test. What my family learned to delight in was met with bafflement or indifference. But that's okay! British humor isn’t for everyone, and it doesn’t need to be.

Here's the thought I'll close with: Taste can be acquired, and it can be cultivated. It goes both ways, for good or for ill. There is no neutral—that’s a myth. This should give us pause and make us consider:

But I didn’t know I was about to get tested when I brought it home from the library. I grabbed it because Quentin Blake’s illustrations appealed to me. It looked fun! (I do judge books by their covers in the children's section of the library, and I am not apologetic about it).

So when I sat down to read it with Martha, I was surprised. How could anyone read this? It was utter nonsense! (To be fair, the subtitle “A Collection of Nonsense Stories, Poems, Riddles & Rhymes” warns of this.) My error was that I failed to remember that nonsense appeals to children—they often think in nonsensical ways. ("Creative" might be another word for it.) But nonsense written for American children is one thing—nonsense written for British children is a bit more of a reach from this side of the pond. (Still, I tip my hat to Michael Rosen and Quentin Blake, both of whom are Englishmen. They really got it right in this book, so much of it sounds like it was simply transcribed from the mouths of children.)

I admit, I almost gave up. I don’t know why we kept reading. Maybe it was the illustrations, maybe it was a desire to get some sort of return on my investment, maybe it was a sense of discovery. For whatever reason, we pressed on. I’m glad we did. The more we read, the more we liked it. The more we liked it, the more we wanted to read.

Martha and I ended up reading the entire book in one sitting—a real feat! It was an amazing and special hour of shared chuckles and laughs. Over the following week we revisited it again and again, often reading aloud our favorites to the rest of the family. By the end of it, our family had several new inside jokes—a shared language for us to enjoy.

It wasn't until I shared this book with friends that I realized that it was a taste test. What my family learned to delight in was met with bafflement or indifference. But that's okay! British humor isn’t for everyone, and it doesn’t need to be.

Here's the thought I'll close with: Taste can be acquired, and it can be cultivated. It goes both ways, for good or for ill. There is no neutral—that’s a myth. This should give us pause and make us consider:

- What are we training ourselves to savor?

- What kind of palates are we cultivating in our kids?

There’s good stuff out there. Go find it, enjoy it, and share it when you do!