I like the format of referencing my old posts at the beginning of my new ones not only because it holds me accountable to addressing what I’ve written before, but also because it helps me see where I might be making errors in my thought process. So I’ll start new posts off referring to what I’ve written previously, but if you ever want to go straight to the new stuff, feel free to skip the blue boxes. In Far, Far Further to Fall, I wrote about exponential growth and the Fed’s initial coronavirus response in the form of the CARES Act. I claimed we could hit 8.7 million cases by April 10 if we didn’t do anything to stem the disease. The good news: by April 10 we had just 492,416 cases in America. Wow, Chris. Not even close… why am I reading this blog, again? A few points: first, I’m relieved to see the numbers aren’t as bad as I thought they might be. I was worried if we didn’t react quickly enough, growth in April would average the same 37% per day we saw in March. So far, the growth rate in confirmed cases is averaging 11% per day and that continues to decline. Over the last ten days, growth has averaged just 8.8% per day.

Daily growth rates in blue are noisy, so I’ve added a 10 day average in red. These lines say basically the same thing, but the red line is a bit easier to read: Confirmed cases were growing at an increasing rate in early March, grew steadily from the middle of March toward the end of the month, and have declined through the beginning of April.

My ongoing concern, however, revolves around testing. These are confirmed cases after all. How many people are contracting the virus but unable to receive a test due to supply shortages? According to Johns Hopkins’s coronavirus dashboard, as of April 13, the US has tested 2.9 million Americans, or less than 1% of the population. Can we restart an economy if we don’t know who has the disease? How do we get more tests? Don’t the tests come from countries that are also shut down? What does ‘restart an economy’ even mean? I think subconsciously we all picture yanking a lawn mower cord really hard maybe multiple times over, but it’s not going to be as straightforward as that. There are plenty of talking heads promising a ‘V shaped recovery’, but that has never really been a possibility. Expect these same figures to walk back their predictions by suddenly realizing second and third waves of infections are possible. All the more reason to keep staying home.

In this week’s post, I want to go over the basics. Why save money? And from there, why care about investment returns? and why care about these things now? While the answers to these questions are simple, most people don’t take advantage of the simple logic they offer. Without paying attention to these vital questions, you leave your financial security — and ultimately a good chunk of your happiness — in the hands of someone else, whether that’s your employer or your government. I doubt I’ll ever work somewhere that offers a pension, and I don’t expect Social Security to have any funding for me by the time I retire. I’d love to be surprised by something different, but I definitely won’t be betting future Chris’s happiness on it…

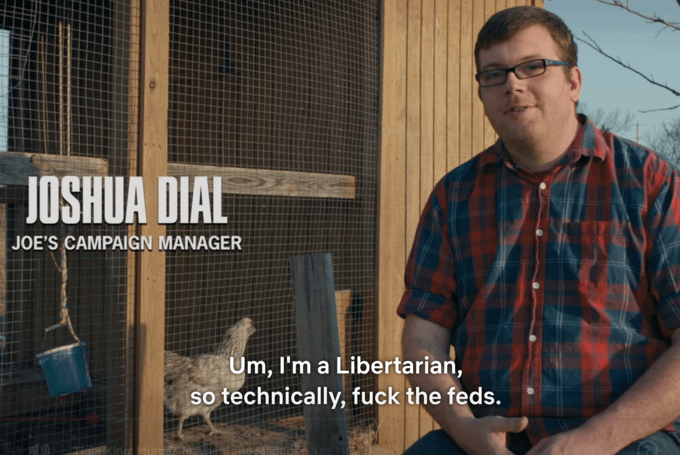

If you haven’t watched Tiger King by now, you never will.

So why save money?

If you play the investing game correctly, you will — at one point or another — make more money doing nothing than doing something.

Ok, nice one liner for twitter Chris, but what the hell does that mean? That means by saving aggressively (a significant portion of your income) and consistently (over long periods of time) your investment portfolio will one day generate more money than the income you make from your job.

Let’s take a look at market returns for the last 30 years — from 1991 to 2020. Remember, market returns are something anyone can generate; all you do is buy an index and hold it. Not only is this strategy effortless, but it has proven to outperform most investment professionals over long periods of time. Say you invested $10,000 in the market on January 1, 1991 and held it through to today. How much money do you think you would have?

How much would $10,000 invested in the market in 1991 be worth today?

- $35,000

- $60,000

- $150,000

- $350,000

If you invested just $10,000 into SPY and never touched it, you’d have over $150,000 today. (You’d have had closer to $180,000 if it weren’t for COVID-19). Of course, hindsight is 20/20 and anyone with money in the 1990s who wasn’t investing missed out. But don’t forget, this period of time was not without its problems: it includes the tech bubble burst of the early 2000s, the second greatest financial crisis in American history in 2008, and now the largest and fastest economic shock ever experienced on a global scale. Despite ALL OF THAT, you would have made a 15x return if you didn’t sell.

The next 30 years may or may not look much like the last 30 years as far as investment returns are concerned, but try to envision what your future could look like if you saved aggressively. How much would you need to start saving today in order to make more money from your investments than your job? Would it take 30 years? How about 15? Could you do it in 10? What would you need to change to make that happen? Maybe your family income chart looks something like the table below. To keep things simple, I’ve assumed the market returns 7% per year, your salary increases by 2%, and you save 30% of your total income — all modest assumptions.

Year | Salary | Investment Income > Salary? | Beginning Value | Add Yearly | Investment Income | Ending Value

2020 | 100,000 | | 0 | 30,000 | 0 | 30,000

2021 | 102,000 | | 30,000 | 30,600 | 2,100 | 62,700

2022 | 104,040 | | 62,700 | 31,212 | 4,389 | 98,301

2023 | 106,121 | | 98,301 | 31,836 | 6,881 | 137,018

2024 | 108,243 | | 137,018 | 32,473 | 9,591 | 179,083

2025 | 110,408 | | 179,083 | 33,122 | 12,536 | 224,741

2026 | 112,616 | | 224,741 | 33,785 | 15,732 | 274,257

2027 | 114,869 | | 274,257 | 34,461 | 19,198 | 327,916

2028 | 117,166 | | 327,916 | 35,150 | 22,954 | 386,020

2029 | 119,509 | | 386,020 | 35,853 | 27,021 | 448,894

2030 | 121,899 | | 448,894 | 36,570 | 31,423 | 516,887

2031 | 124,337 | | 516,887 | 37,301 | 36,182 | 590,370

2032 | 126,824 | | 590,370 | 38,047 | 41,326 | 669,743

2033 | 129,361 | | 669,743 | 38,808 | 46,882 | 755,433

2034 | 131,948 | | 755,433 | 39,584 | 52,880 | 847,898

2035 | 134,587 | | 847,898 | 40,376 | 59,353 | 947,627

2036 | 137,279 | | 947,627 | 41,184 | 66,334 | 1,055,144

2037 | 140,024 | | 1,055,144 | 42,007 | 73,860 | 1,171,012

2038 | 142,825 | | 1,171,012 | 42,847 | 81,971 | 1,295,830

2039 | 145,681 | | 1,295,830 | 43,704 | 90,708 | 1,430,242

2040 | 148,595 | | 1,430,242 | 44,578 | 100,117 | 1,574,938

2041 | 151,567 | | 1,574,938 | 45,470 | 110,246 | 1,730,653

2042 | 154,598 | | 1,730,653 | 46,379 | 121,146 | 1,898,178

2043 | 157,690 | | 1,898,178 | 47,307 | 132,872 | 2,078,358

2044 | 160,844 | | 2,078,358 | 48,253 | 145,485 | 2,272,096

2045 | 164,061 | | 2,272,096 | 49,218 | 159,047 | 2,480,361

2046 | 167,342 | Yes! | 2,480,361 | 50,203 | 173,625 | 2,704,189

2047 | 170,689 | Yes! | 2,704,189 | 51,207 | 189,293 | 2,944,688

2048 | 174,102 | Yes! | 2,944,688 | 52,231 | 206,128 | 3,203,047

2049 | 177,584 | Yes! | 3,203,047 | 53,275 | 224,213 | 3,480,536

2050 | 181,136 | Yes! | 3,480,536 | 54,341 | 243,638 | 3,778,514

2020 | 100,000 | | 0 | 30,000 | 0 | 30,000

2021 | 102,000 | | 30,000 | 30,600 | 2,100 | 62,700

2022 | 104,040 | | 62,700 | 31,212 | 4,389 | 98,301

2023 | 106,121 | | 98,301 | 31,836 | 6,881 | 137,018

2024 | 108,243 | | 137,018 | 32,473 | 9,591 | 179,083

2025 | 110,408 | | 179,083 | 33,122 | 12,536 | 224,741

2026 | 112,616 | | 224,741 | 33,785 | 15,732 | 274,257

2027 | 114,869 | | 274,257 | 34,461 | 19,198 | 327,916

2028 | 117,166 | | 327,916 | 35,150 | 22,954 | 386,020

2029 | 119,509 | | 386,020 | 35,853 | 27,021 | 448,894

2030 | 121,899 | | 448,894 | 36,570 | 31,423 | 516,887

2031 | 124,337 | | 516,887 | 37,301 | 36,182 | 590,370

2032 | 126,824 | | 590,370 | 38,047 | 41,326 | 669,743

2033 | 129,361 | | 669,743 | 38,808 | 46,882 | 755,433

2034 | 131,948 | | 755,433 | 39,584 | 52,880 | 847,898

2035 | 134,587 | | 847,898 | 40,376 | 59,353 | 947,627

2036 | 137,279 | | 947,627 | 41,184 | 66,334 | 1,055,144

2037 | 140,024 | | 1,055,144 | 42,007 | 73,860 | 1,171,012

2038 | 142,825 | | 1,171,012 | 42,847 | 81,971 | 1,295,830

2039 | 145,681 | | 1,295,830 | 43,704 | 90,708 | 1,430,242

2040 | 148,595 | | 1,430,242 | 44,578 | 100,117 | 1,574,938

2041 | 151,567 | | 1,574,938 | 45,470 | 110,246 | 1,730,653

2042 | 154,598 | | 1,730,653 | 46,379 | 121,146 | 1,898,178

2043 | 157,690 | | 1,898,178 | 47,307 | 132,872 | 2,078,358

2044 | 160,844 | | 2,078,358 | 48,253 | 145,485 | 2,272,096

2045 | 164,061 | | 2,272,096 | 49,218 | 159,047 | 2,480,361

2046 | 167,342 | Yes! | 2,480,361 | 50,203 | 173,625 | 2,704,189

2047 | 170,689 | Yes! | 2,704,189 | 51,207 | 189,293 | 2,944,688

2048 | 174,102 | Yes! | 2,944,688 | 52,231 | 206,128 | 3,203,047

2049 | 177,584 | Yes! | 3,203,047 | 53,275 | 224,213 | 3,480,536

2050 | 181,136 | Yes! | 3,480,536 | 54,341 | 243,638 | 3,778,514

In just 26 years from an asset base of zero, you’re making more money through your investment portfolio than you are at your job.

Of course, salaries don’t grow forever and maybe you start earning equity (stock options!), but that would just further accelerate my point that your investment income will eventually outpace your salary. What does that get you? The freedom to do whatever you want. No longer tied to a job, you can live whatever life you choose bound only by the earnings potential of the asset base you have built up. It’s a fun life to think about.

Unfortunately, for most people, that day never comes, and that really is a shame. Everyone should have the chance to create a system where their wealth begets more wealth, but that isn’t the world we live in yet. Most people reach their spending peaks when their children are growing up — school and extracurriculars aren’t cheap — but because their savings rate isn’t high enough, their consumption necessarily must come down in retirement. 1

After age 54, most see their income and expenditures drop. But wait, I thought people called retirement the golden years? Maybe copper years is more like it. Part of the reduction makes sense — by your late 50s you’ve likely bought the high ticket items that most households purchase in their lives like a house and college for the kids — but how much of that expenditure reduction is driven by necessity?

I guess what I’m getting at is twofold: if you have the means to save and you’re not saving, you’re putting more pressure on Future You to do the heavy lifting in the same way that Future Us is going to have to figure out how to pay for the trillions of coronavirus stimulus we’re pumping into the economy. If we’ve learned anything from the virus, it’s that even if you are willing and able to work, you may not be allowed to. Second, if you don’t have the means to save because your expenses are too high, you should cut spending. If you don’t have the means to save because your income is too low, that’s a different and more difficult path, but the logic is the same. Get to a place where you can save and save relentlessly.

I realized the other day that if I were to work from now until 65, that would require another 36 years on top of my what-I-already-thought-was-a-long 6 year career. I’ve been alive for 29 years, so take all the memories I’ve ever created and add 7 years (or 1 mediumly healthy dog’s life) on top of that, and I’m at retirement. That’s a long time to be working. Why not save?