Writing

W1. "Getting Started with Privacy First Data Science": A little blog post I put together on how to recursively calculate means and variances. Useful because you don't have to keep individuals's data, but can do pretty much the same data science on aggregate populations that you were doing before.

W1. "Getting Started with Privacy First Data Science": A little blog post I put together on how to recursively calculate means and variances. Useful because you don't have to keep individuals's data, but can do pretty much the same data science on aggregate populations that you were doing before.

W2. "3 Key Responsibilities of a (Research) Manager": strategy, workflow, hiring.

Reading

R1. People and Cookies: Imperfect Treatment Assignment in Online Experiments (Coey and Bailey 2016): The specifics of this paper are perhaps becoming less relevant as tracking cookies become less of a thing in the measurement of online advertising, but the paper's gist is pretty important:

Identifying the same internet user across devices or over time, is often infeasible. This presents a problem for online experiments, as it precludes person-level randomization. Randomization must instead be done using imperfect proxies for people, like cookies, email addresses, or device identifiers. Users, may be partially treated and partially untreated as some of, their cookies are assigned to the test group and some to the, control group, complicating statistical inference. We show, that the estimated treatment effect in a cookie-level experiment converges to a weighted average of the marginal effects, of treating more of a user’s cookies. If the marginal effects, of cookie treatment exposure are positive and constant, it underestimates the true person-level effect by a factor equal, to the number of cookies per person.

R2. The Diff: Framing is important--investment decisions edition. This is a pretty great observation:

C-level Fortune 50 executives spend more time worrying about the nature of truth than freshman philosophy majors. Accounting, which looks so precise and scientific at the level of income statements, is the convergence of a long series of assumptions, many of which are audited imperfectly and rarely stress-tested.

This uncertainty creates a potentially crippling coordination problem both within companies ("how do we know where we stand?") and between investors and companies ("how do we know where you stand?"). The solution is often to coordinate around a particular set of somewhat arbitrary accounting rules--basically a frame of how businesses are successful, or not. For example:

Today, investors do understand subscription models well. Salesforce may have created more aggregate market cap for the rest of the industry than it captured for itself, first by giving investors the right vocabulary and later by giving them a compelling comp.

"The right vocabulary" gives people the ability to envision success in a new way and can make it normal. Of course the "compelling comp" is also critical. Evidence for the correctness of the vision needs to be forthcoming. People imperfectly, but eventually, update their priors.

This piece also has a great historical footnote of examples where new accounting metrics--new vocabulary/frames--didn't work out:

The record of companies that pioneer new accounting metrics is mixed. Some conglomerates have special definitions of profits they like to cite, like Roper's cash return on investment and Berkshire's look-through earnings. And John Malone did an altogether too-good job of selling investors on the merits of EBITDA, which makes sense for a business that has high depreciation relative to incremental capital expenditure needs, but often gets used to make businesses with ongoing capex needs look cheap. The "Novel Non-GAAP Metric" portfolio would have some spectacular winners, but plenty of messy eyeball-related losers, too.

R3. Earliest Know Uses of Some of the Words in Mathematics (and its companion Earliest Uses of Various Mathematical Symbols): I'm a big fan of understanding the history of scientific/mathematical terms as a way to better understand those terms. Terms are developed to convey ideas to particular people in particular times. If you aren't one of those people in one of those times, they can be very confusing. Reaching back to those times is helpful for understanding and remembering. For example, on the Not So Standard Deviations podcast, the hosts were discussing how confusing the term "one hot encoding" was for them. Why didn't people just say binary or dummy variable? The hosts have backgrounds in statistics, where the latter terms are common, not machine learning were one hot is common. When they learned the origin of the word--see digital circuitry Wiki--they commented on how they would likely not forget the term again. These math history websites should be a great resource for making these kinds of connections for mathematical concepts and symbols (though they definitely need to diversify the panel of pictured mathematicians).

R4. A World Without Email (Newport): One of the more interesting parts of this book is not that email, Slack, and the resulting "hive mind" are stressful and ineffectual, but the reason that we continue to put up with this stress and inefficiency is that it is easy in the moment--it's a time inconsistency problem. How do we escape this trap? By living the world we want to create--focusing on the problem, consistently experimenting, and not getting distracted along the way, by short term inconveniences. He motivates this by describing the process Henry Ford used that culminated in huge efficiency gains, but produced a lot of inefficiency along the way. For example, he created specialised machines to do specific tasks, but a new specialised machine is prone to frequent malfunction and could hold up the assembly line. Ultimately, the kinks would be worked out and, brought together with other improvements, dramatic productivity gains were realised.

Two other key takeaways for me:

- Distinguish (both for yourself as a manager and your team) work execution and workflow. Going back to Peter Drucker, knowledge workers are seen as needing significant autonomy. Their manager might not even know how to do their specialised and creative job. Newport argues that this is certainly true of work execution, but that workflow processes benefit from more structure. Without it, we are swamped with emails and slack messages; distracting us from work execution.

- Don't extensively explain your plan to be more productive to external stakeholders, just be more productive. They will be annoyed if you explain it to them (it's likely to be taken as an accusation that their workflow isn't productive) and it will be a test of whether or not you are actually being more productive.

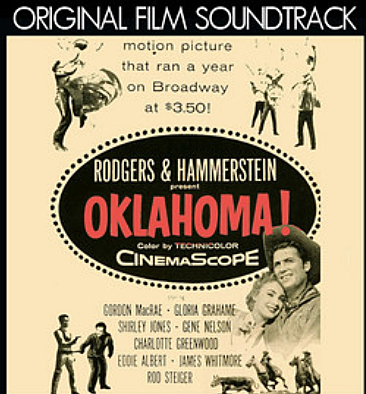

R5. I'm on parental leave at the moment and spending a lot of time singing show tunes to a two month old. Oklahoma! is a particular favourite of the little one. The soundtrack album art on Spotify uses a different form of persuasion than I'm familiar with in recent advertising:

Motion picture that ran a year on Broadway at $3.50!

Not only did it run for a long time on broadway, but they could charge so much money for it! Oklahoma was on Broadway in 1943. I guess even more impressive that they could charge so much during World War II hardship 🤷♀️.

The musical overall is pretty darn problematic. . .

R6. To close this week's reading list, a small wiki rabbit hole: “Scare quote” was coined by E. Anscombe in an essay called “Aristotle and the Sea Battle” (Wiki). The Greeks had a symbol for indicating irony or dubiousness called a diple periestigmene (⸖). A version lives on in the French guillemets (<<>>).