There's this scene in the 90s movie Se7en where the detectives played by Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman are able to hone in on the serial killer via a secret FBI program that monitors people's library habits. The killer, played by Kevin Spacey, has been reading Dante's Divine Comedy, Milton's Paradise Lost, and other books about the seven deadly sins, and he's been borrowing those books from the library. That's how they get him.

This plot device was likely inspired by a real program started by the FBI in 1973 called the Library Awareness Program. It was revealed by the New York Times in 1987, leading to congressional hearings and librarians forming a code of conduct not to rat out their patrons' reading habits.

I've been thinking about how this scene, and the real-life program that likely inspired it, recalls how Americans used to have a deep appreciation for the idea that what you read is none of anyone's business.

It's not hard to see why this used to be such a strongly-held principle. In 1987, with the Cold War still on, and the memories of the Are You Now Or Have You Ever Been A Communist inquisition still fresh, people surely weren't keen to be outed for having an interest in the writings of Karl Marx or other socialist writers. Neither to the FBI nor to their fellow Americans behind those white picket fences.

How bizarre it would have seemed back then to learn that in the future your reading habits would not only be tracked forever by Big Tech, and thus available to any agent with a subpoena, but broadcast to the world in a variety of uncomfortable ways. Like, oh, the fact that who you follow on Twitter is public for all to see (and judge).

As the cancelation drive accelerates in the US, I've for the first time thought about how my own reading habits might be scrutinized. How following certain people on Twitter can be cast as "toxic behavior". We're well into the phase where the rings of incrimination are spreading. It's bad to be the original author of subversive writings, but it's increasingly bad to be a reader as well.

I've been on Twitter for a long time, and over the years I've certainly had my fair share of controversies and pushback. Tweeting about Bitcoin stands out as a topic that would often attract a brigade of boosters eager to educate me in forceful ways about just how wrong I was about crypto. But that is now a faint memory compared to any time I dare retweet the writings of Glenn Greenwald or Matt Taibbi.

Now, I invite that on by choosing to publicly flaunt that I read both, but the tone of the feedback is a public flaunt too. A clear signal that to some people, even reading these writers is now a serious cultural transgression. I'd certainly forgive anyone not looking to risk those condemning eyes for refraining from having either writer in their public following list on Twitter.

It's bizarre you can't easily make your reading habits private on Twitter. You either have to hack the system with private lists, turn your account private, or keep a separate burner account with your subversive reading list. That's backwards.

Email has it right. As long as you're not using Gmail or other Big Tech surveillance systems, who you write, who you read, and particularly which newsletters you subscribe to is none of anyone's business. As it should be.

What's so nuts about the current atmosphere is how outlandish it seemed even five minutes ago. When Republican congress members wanted to drag the Big Tech antitrust discussion into "conservative censorship" last summer, I rolled my eyes. Then followed the crude suppression of the Hunter Biden story from the NYPost, Parlor's destruction, a cancelation drive that was hard to keep up with, and the endless consternation over when someone should lose the privilege to publish on the internet.

I don't roll my eyes any longer.

Which is also not the same as buying into the full conservative grievance arc, the nonsensical proposed remedies (revoke 230!), or even having a final opinion on how to address social media's role in spreading QAnon or vaccine conspiracy theories. These are big, difficult questions. And it's clear that we don't have big, easy answers. (Though we could start by defunding the incentive to spread by banning targeted advertisement!).

But it has given me a renewed vigor to seek out subversive, alternative voices. To broaden my reading habits further, rather than shrink them down. And to hope others are able to do the same, without fearing the social pressure within their tribal circle, because they can do so in private.

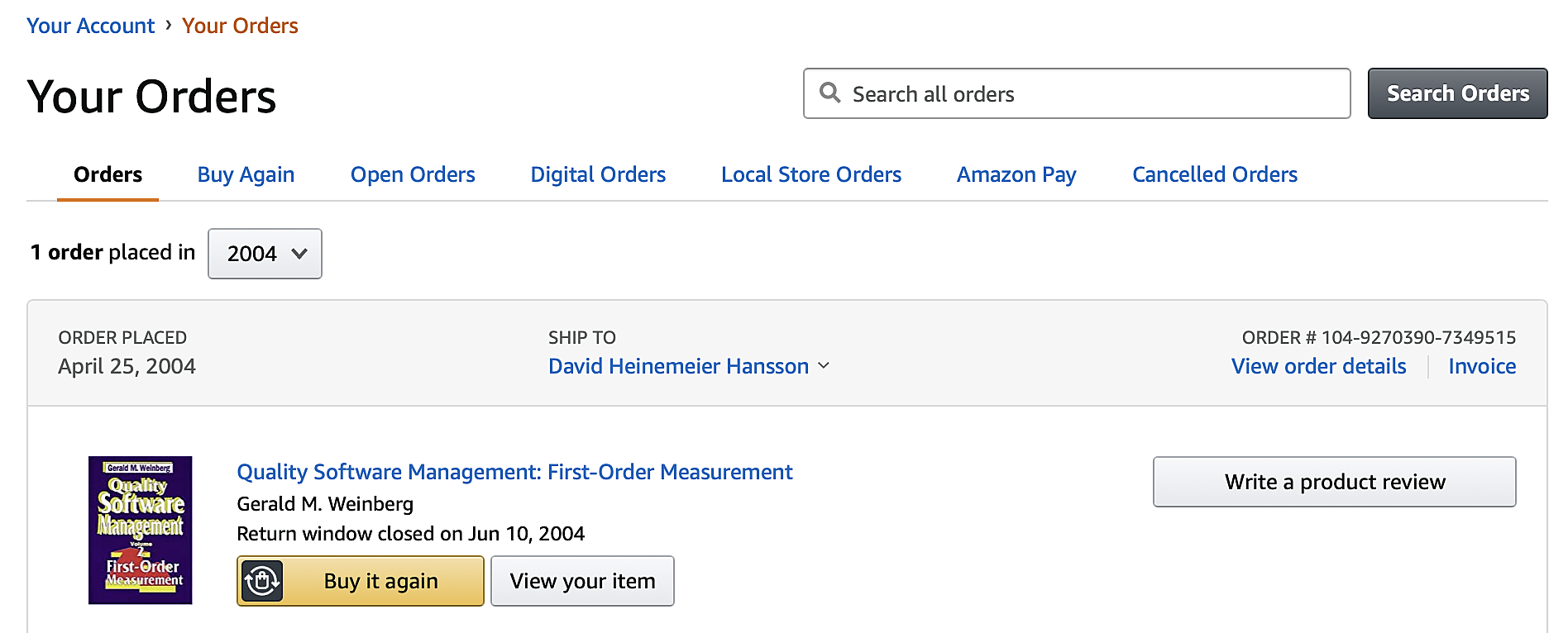

We need to bring back the idea that custodians of your reading habits, be they librarians or social media operators or online book sellers, should take a professional oath to keep your reading habits private. That you should feel free to read writers across a broad spectrum, even, or perhaps particularly, if you don't generally agree with them.

We need to rediscover that vintage spirit of what you read being none of anyone's business.