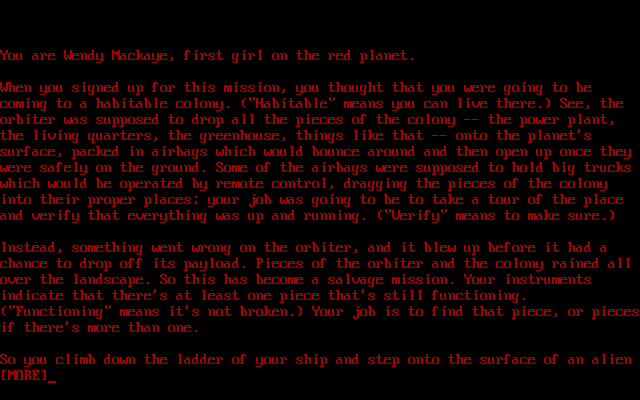

The most comfortable writing I've ever seen was written in the dialogue box of a video game somewhere, published on a small screen. In game design, particularly in games centered on things that aren't writing, words are purely functional. Every sentence is at once meticulously tuned and somewhat careless; it must be precise, and at the same time it's fundamentally beside the point. The tinier the box, the more (and the less) each word matters.

Someone once said that comic books and jazz were the two quintessential 20th-century American art forms. The two have somewhat opposite reputations: jazz is seen as unpopular, too arty and intellectual, intolerably formless, while comics were typically seen as too simple, primitive in scope and philosophy. Neither, of course, is true. Jazz is simply made of different units of music, constructed differently, demands a different approach to listening. And while individual panels of comics are simple, it's that crudeness that lends such potency, and demands increasingly subtle elegances from the artists who work within their frames. Besides, as everybody knows, it's the combination of the pieces that matters. Every language has different rules, and allows for different masterpieces. That's as true of mediums as it is of languages themselves.

Every form expresses itself differently. And forms are far more varied than our usual categorizations imply. The potential variance between different novels is astounding: you would not believe what Finnegans Wake reads like, you would not be able to imagine it, without opening up to its first pages and being struck with the very idea of it like a thunderclap or a slap to the face.

People will sometimes tell me that they "like" or "do not like" poetry, as if there aren't infinite varieties of what a "poem" can look like. Robert Frost eschewed conventional forms, yet also said that a poem without any form was like a game of volleyball without a net. Richard Siken's Crush is at once self-consciously artsy-fartsy and shockingly accessible, in the way that adolescent dreams are both incoherent and universally devastating. When I read poetry, it's often by spontaneously buying books by poets I've never heard of, because one poem struck me enough that I want to figure out the rest of them. The individual poems, the individual phrasings and sentences, may hold meaning to me, but a collection of poems is like a portal to another world. It's less like exploring a poet's mind or life or artistry, and more like abruptly feeling the way their chest rises and falls as your head rests against it, experiencing their breath with the whole of you at once.

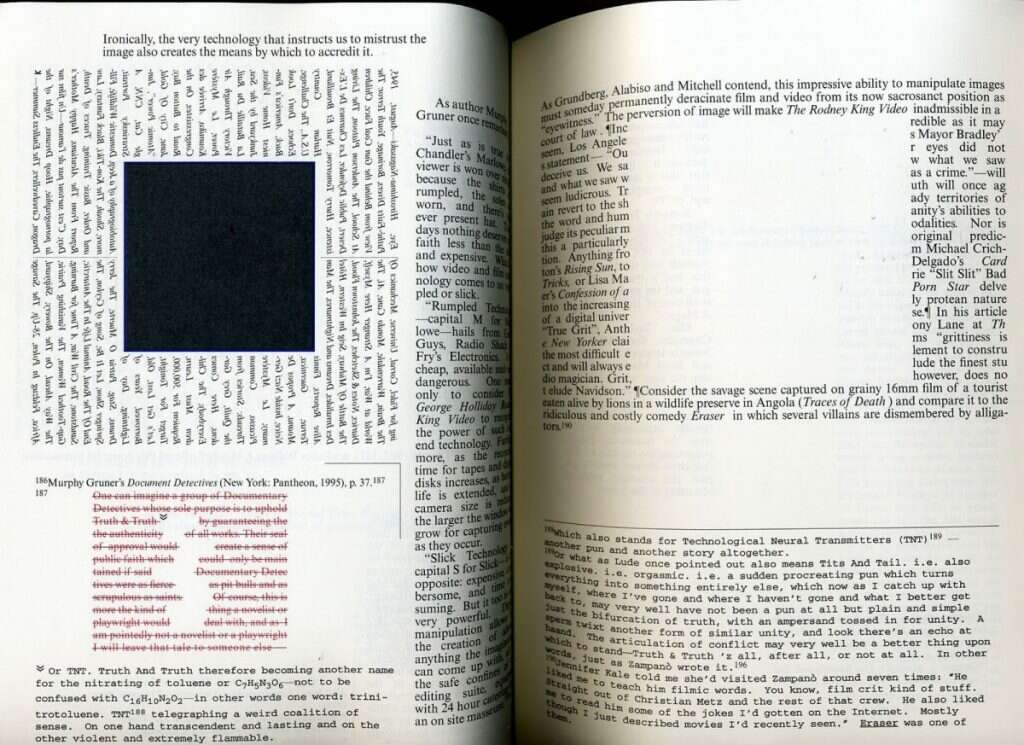

I recently found myself reading Jacques Derrida's "Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of Human Sciences" late one night. Derrida, whose use of the word "grammatology" I stole for my title here, is an infamously difficult writer—few people cherish his use of language for its own sake. I get something out of reading him, so I force my way through him when the impulse strikes, however late. At the same time, I am aware that I discovered Derrida in perhaps the lowest-brow manner, which is to say I read about him in House of Leaves (pictured above).

House of Leaves made a huge impact on me, and remains one of my favorite things to reread. Curiously, though, virtually none of that impact has anything to do with the quality of its writing. As a novel, and as a scary story, its thrills are born of sheer composition. And Mark Z Danielewski, who's said that his greatest influence was not literature but the cut-centric rhythm of film, has a masterful ability to make a page-turner out of pieces that don't feel like they could possibly be compelling. The centerpiece of the novel is an essay about filmmaking, and while the joke is how frequently it devolves into pure narrative storytelling, the frequent discussions of philosophy and aesthetics delve far deeper than you'd expect a bestseller to go, bringing up the likes of Derrida in non-trivial ways—albeit punctuated by the novel's other narrator, who is continually frustrated and outraged by what he perceives as sheer pretension.

Is an essay on authenticity in film the stuff of horror? I can't imagine it being nearly as disturbing or as frightening in any other context, nor as gripping. Yet House of Leaves, by leaning further into the strangeness and telling its story through such increasingly bizarre compositions, transmutes obscure academic jargon into strangely addictive prose. The language changes the story. The meanings shift. Lofty concept and visceral experience, rather than conflicting with one another, are revealed to be one and the same.

One of the most frequent bits of feedback I get when I write online is: "I didn't expect to read that whole thing." I take perverse pleasure in writing things that seem too long and too dense for the mediums they're published in. I also have more than a bit of a knack for making those things work. I like seeing just how much I can get away with, and I've been delighted, over the years, to discover new ways of getting away with more and more.

Occasionally, people act like I'm expecting some kind of commitment from my readers, or demanding that they dedicate themselves to me. But if there's a secret to how I write, it's that I understand that most digital mediums are designed to be essentially meaningless. Your TikTok algorithms, your newsfeed, your Spotify playlists, are designed to push you frictionlessly through as much content as you have time to take it in. The individual pieces doesn't matter. The topics, the authors, the memes and weeklong dramas, are all interchangeable: the experience is the app, not the individual. Given that, paradoxically, there's no reason not to find yourself reading a longform essay for half an hour or an hour or even two. What is reading online but scrolling, anyway? When you're committed to a certain waste of time, what would possibly push you away from me, when pushing away takes more effort than continuing to listlessly bob along?

I've published a lot of things in a lot of places, oftentimes quite successfully. Sometimes, people are taken aback by how much I write, and how quickly, and how readably. (Your mileage may vary.) The trick is that these things are one and the same: I don't put a lot of thought into my writing, trusting that my natural "speaking voice" will be more comfortable than whatever I try to edit myself into. I write online the way I read online: impulsively and with more of a focus on vibes than on thought. That's not to say I don't think—it's to say that I trust the thoughts to come out in their own way, colloquially and easily. The length is a part of that, not a foil to it. It gives otherwise-tricky concepts room to breathe and grow.

It's an easy way of writing, maybe even a lazy one. Do I think it's the best possible way to write? Not at all. But that's because, to my mind, the best possible way to write is to devise structure. If I want to write seriously, I need to take structural development seriously. Which is my way of saying: if I'm writing on somebody else's platform, rather than publishing from my own, you can expect that I'm being fairly unserious. I'm like an artist splashing paints across a canvas just for the mechanical joy of painting, only the canvas I'm filling is some arbitrary digital medium that I get to stuff with whatever feels fun to stuff it with.

Derrida argued that writing is too-often seen as a crude replica of speech, the lesser mode in every way. Similarly, I would argue that the language of form is too-often seen as the crude thing which houses "meaningful" writing. Platform is an afterthought. The mechanics of printing and publication, the means by which we access what we read, are acknowledged in passing without being dwelt upon.

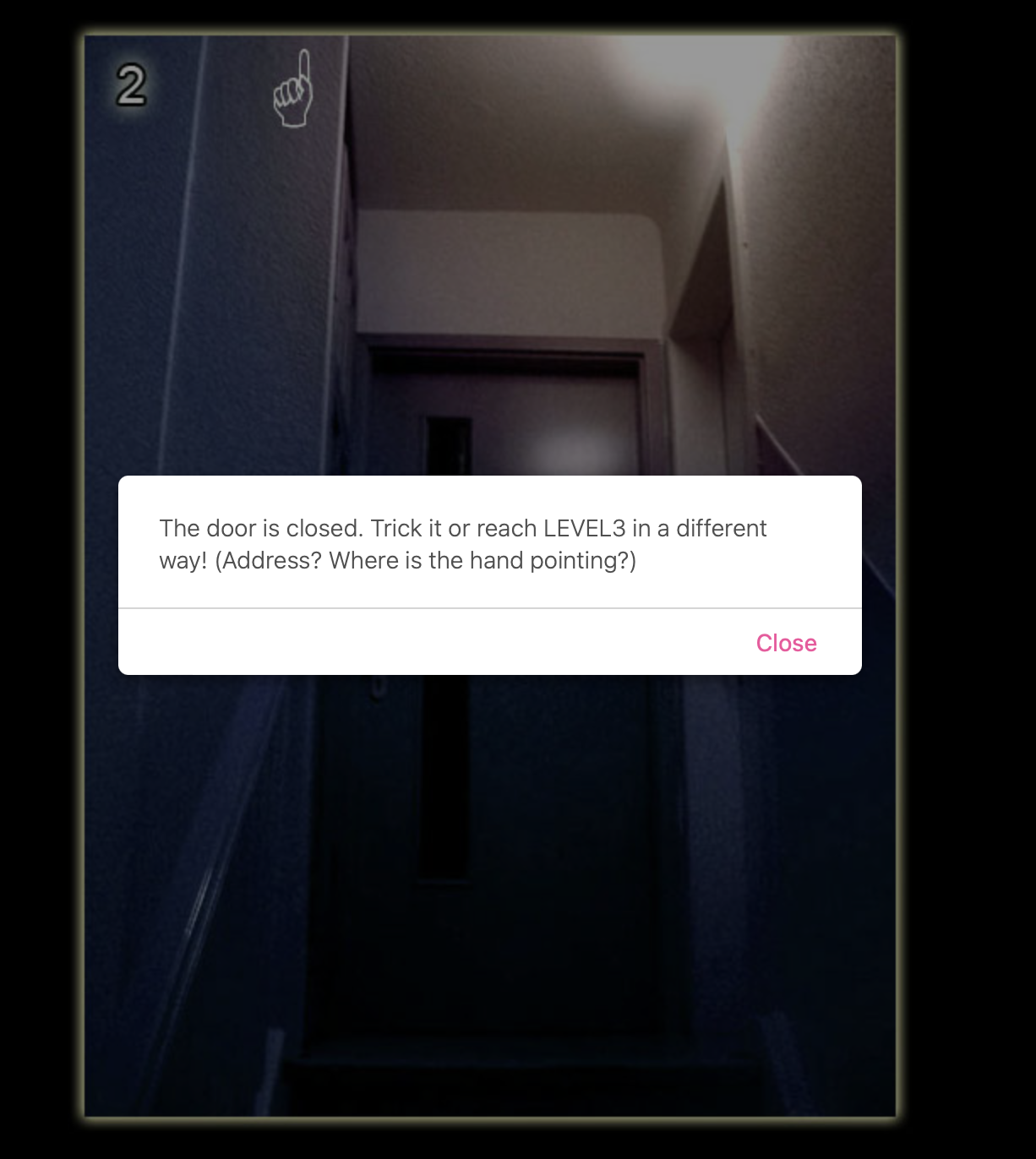

When I say that I've never felt more comfortable reading text than when it was on a tiny screen, I'm getting at something more than retro fetishization or some twee embrace of an aesthetic. I'm talking specifically about the propulsiveness of text whose function could not be clearer, whose effectiveness can be monitored by how many times you have to physically press the A button to advance. (I've been playing a game with text prompts recently, and it's infuriating how many sequential paragraphs the author tries to cram into their narratives, five pages of dialogue forced down their player's throat sentence by sentence by sentence, thirty messages back-to-back before the game advances in any way. You can literally feel the medium pushing back.)

When a medium is imprecise, I feel no need to reward it with precision. When I want to be precise, I find the proper medium to express that precision in. Everything else is just a puppet show, this included.

The true uniqueness of digital mediums is interconnection: the stitching-together of discrete pieces into a feed, the intentional composition of branching paths, or the hidden worlds contained within a game, each willing to open only to the player who participates in just the right way.

Past a point, the line between author and reader blurs. But that works in both directions. When you participate on a social platform, are you truly functioning as a creator? Or are you just another consumer, responding to invisible guidelines, your independent acts of creation bent towards a not-quite-visible purpose? At what point does algorithm-driven content creation rob the word "creation" of its original meaning? What does it mean to see a platform as a creative medium, rather than as a prescriptive one? And is there a way of differentiating between the kinds of "play" that conform to the rules of a game, and the kinds that involve twisting those rules into a language of their own?

Brian Eno once famously said that every medium is defined, not by its perfections, but by its flaws. Records are defined by the hiss and crackle of the needle on vinyl. VHS is all lines of noise and deteriorating tape. Eno also, unrelatedly, said that the key to any successful perfume is not its sweetness but its stink: the thing that intrigues you even as it pushes you away.

I tend to think of languages as vast sets of failures. They are an attempt to translate phenomenological experience (Derrida phrase!) into something neat, something simple, something that fits a pattern. Writing, in one sense, is an ongoing attempt to break language, to trick it into doing things it was never designed to do. The most memorable writers put words together in ways that feel implausible. If language is a system, then writing is a hack.

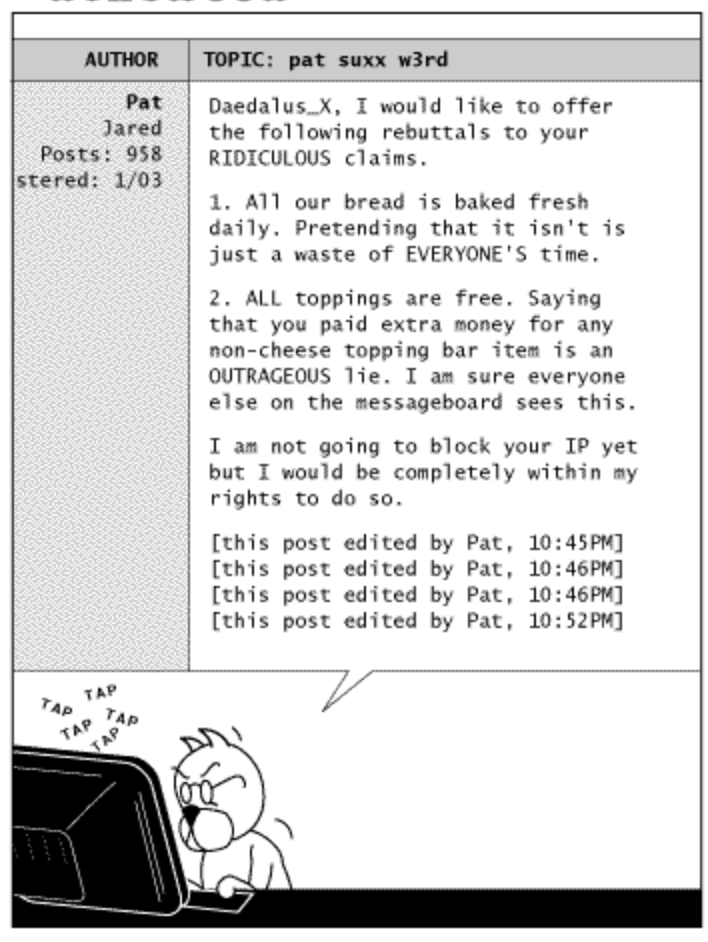

Mediums only become interesting when people start embracing those flaws: when TV stops trying to look like film, just like a century ago film's breakthrough happened when it stopped trying to mimic theatre. The aspects of digital communication that people scoff at—the misspellings and uneven punctuation—are by far their most expressive features, and the ones that change genuine language the most.

To speak the language of platforms, then, is to think of them in terms of the ways that they can break. To embrace glitches or bizarre choices or failures of user experience. To think of both how they shape language and how they frustrate it.

A platform which doesn't break in interesting ways is not an interesting platform. By its nature, any individual platform will be insufficient. Its mutations hold the key to its vitality, and every breakage is a new mutation. Just like language itself. (Shakespeare is credited with inventing 1,700 different words, which is another way of saying that Shakespeare found 1,700 different reasons to break the English language as he knew it.)

As for me, the perennial struggle is between saying things I care deeply about saying, and discovering the proper ways to say them. The more something means to me, the more I feel I can only say it in one true way, one single encapsulating form whose very nature is yet another expression of the thing I feel compelled to express. Because the words themselves can never be enough. Only through triangulation, only by expressing what I'm expressing with both words and wordlessness, do I have a shot of pointing at the idea behind the idea.

If I say it right, you will know immediately that I have said it. Everything about its language—far more than just its words—will tell you so. The words will also be precise in a way these words are not. Perhaps you'll wonder, looking back, why I choose to write that way then and not now. And the answer is simple: the medium engenders the language, not the other way around.