Numbered, to preserve the illusion of order and intention.

- The tragedy of Mike Schur is that he is capable of writing exactly two-and-a-half brilliant seasons of any sitcom, but is doomed to be so popular that he has never once produced a brilliant two-and-a-half-season show. He's the rare writer who'd benefit from being canceled now and again.

- The triumph of The Good Place is that it loaded its first two brilliant seasons up front, without the typical rev-up season that Schur burns through. A lesser triumph is that The Good Place's final good half-season is scattered throughout seasons 3 and 4, which is almost enough to make it seem like it holds up.

- All of my opinions on The Good Place, which I rewatched on impulse over the weekend and start of this week, are colored by the fact that my best friend has been choking down Schur's Good Place-inspired How to Be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral Question, venting her pain by means of texting me excepts of his turgid pap. Me, ostensibly her close friend. Ostensibly somebody she should primarily want to show compassion and keep safe from harm.

- I have not read How to be Perfect in its entirety, yet feel comfortable saying, from the excerpts I was screenshotted, that it is not a good book. Moreover, it is not-good in ways that call to attention certain not-good qualities of The Good Place, which is a bummer.

- I would like to make it clear at this point that I quite like Mike Schur, to a healthy parasocial extent. He seems like a nice, funny, cool guy. One of 30 Rock's funniest and most obscure jokes is a fond jab at Schur; Mike Schur himself was very funny in his one Parks and Rec cameo. He was funny and popular back when he was a sports blogger, before he had a sitcom of his own at all. It's trendy to hate on Schur himself, for either his omnipresent sitcommery or for his particular blend of politics, plotting, and humor, all three of which trend towards "lukewarm"; however, I suspect he's a swell guy. I've also watched all of his sitcoms to date—even Rutherford Falls, which is doomed to fail because it's on Peacock.

- Moreover, Mike Schur's impact on his industry extends well beyond whether or not his sitcoms are "great" or even "good". He has pushed aggressively for increased diversity on his shows—not just in terms of casting, but in terms of his writers' rooms and his choices of directors. Brooklyn 99 and Rutherford Falls have each broken ground in that direction. Even if you're not particularly invested in diversity and inclusion, or think that Schur's approach to it falls short, it's been widely commented on that Schur has taken impressive steps towards establishing safe, comfortable workspaces for all of his employees, aggressively pushing back against the idea that "divas" or "auteurs" should be free to treat other people like shit. Television is a toxic cesspit, and Schur's attempts to fix that—and to demonstrate that critical and commercial success don't rely on toxicity, a myth that plenty of people in theatre-adjacent fields believe in much too much—are a net good for his industry.

- I also need to point out that The Good Place, particularly its early seasons, really is a triumph of concept, plotting, tone, even cinematography. Though it's technically a fantasy, it masquerades as soft science fiction, both in the corporatist/technocratic leanings of its heaven-and-hell-alike and in the way that it treats its universe like it's computer-derived machinery. All four of its seasons have narrative propulsion, to the point that even a single episode where only minor plot progression occurs feels static (whereas in any other sitcom this would be considered the norm). And on some level, its unstated premise—"what if Silicon Valley invented heaven, and heaven sucked in all the ways that Silicon Valley sucks?"—is not only canny, but executed on shockingly well.

- On top of that, The Good Place nearly cracks what I think of as the central Mike Schur dilemma. In short: Mike Schur has made it clear that the shows he likes involve fundamentally lovely people overcoming their differences and getting along, which is diametrically opposed to the things that make sitcoms and comedies in general good (tension, character flaws). To be fair, The Good Place mostly solves this by wiping the brains of its central cast approximately once per season, but hey: it does fun things with that, it genuinely allows for new compelling plots to arise, and it was a neat attempt to square the circle, even if it failed.

- The central issue that The Good Place runs into, predictably, is that Mike Schur's grasp on moral philosophy is extremely limited. I don't mean that in the sense that he's unintelligent: I mean it in the sense that he's wary of tackling the thorny issues that make moral philosophy worth exploring in the first place. Those issues are frequently political in nature, often touch upon religion, and require some amount of backbone when you address them, or else everything you'll do winds up toothless.

(Backbone? Toothless? I'm mixing a metaphor here, but "gelatinous blob of flesh" works as a descriptor here on the whole.)

The problem is that Schur doesn't avoid politics or religion; that's baked into this show the same way it's baked into all Mike Schur shows. Mike Schur politics are vaguely Democrat, lean heavily in the direction of diversity but only to the extent that "diversity" doesn't mean rocking the boat—you can make your main character bisexual, so long as she only kisses men—and typically treat politics as individual rather than systemic. What matters is that one individual is sexist or racist or mean; structural racism and sexism and sadism don't exist. Ironically, the fact that The Good Place posits a literal dimension full of demons whose entire purpose is to be racist and sexist and sadistic only reinforces how little the show cares to explore the implications of what this means.

Similarly, the first episode of The Good Place stresses that this isn't heaven or hell in a specifically Christian sense; in fact, we are told, every major religion got "about 5% right." What a convenient balance! Of course, 90% of The Good Place is expressly Christian in design, with the last 10% typically coming out of a half-baked sense of Buddhism. There's no indication of what Judaism or Islam or Hinduism or Sikhism or Taoism "got right" within The Good Place, but that's not the point. The point is that we're not supposed to take this schema of the universe too seriously, except for when the plot revolves around our taking it seriously, and episodes slow to a crawl as characters debate metaphysics.

Similarly, philosophy itself is not the point, even when it's the center of the plot. When philosophy is "seriously" contended with, it mostly serves as a prelude to a farce, which would be fine except that philosophy's other purpose is to be excerpted and misquoted en route to solving our protagonists' moral dilemmas. Philosophy, we are meant to believe, is a series of nice quotes you can knit into pillows; if you take those quotes seriously enough, they will lead you to happiness. "Happiness," here, is a mixture of Beatles lyrics and pop-psychology: undo your traumas, actualize and achieve, and remember, love is all you need. - I would like to restate that the problem here isn't philosophical, it's narrative. Your worldview can be garbage as long as you're writing a good story. But when your story insists on orienting itself around philosophical matters, questions of good and evil—when your grand finale is literally an attempt to answer what it would mean to be at peace with yourself, and what utopian eternal life would look like—then suddenly it matters if your Theory of Everything is crap.

- My recommended "rewatch order" of The Good Place is as follows: watch the first two seasons, skip the first half of season 3, skip the first half of season 4, skip as much of the rest of season 4 as you can tolerate. Ideally, your first watch would consist of the entire show, but it's amazing how little the openings of every season matter. (You could pull this same trick with season 2, but at least season 2 opens with a handful of stellar episodes.)

The Catch-22 the show repeatedly finds itself in is: it loves throwing its characters into new situations, but completely stalls every time it does. The first half of every season involves bringing its characters back to the point where the show can act like it didn't wipe their memories, didn't throw them back on Earth or into a new afterlife or what-have-you, and can introduce genuine plot development, which here means expounding more on its cosmology and teasing out a possible happy ending for its band of misfits.

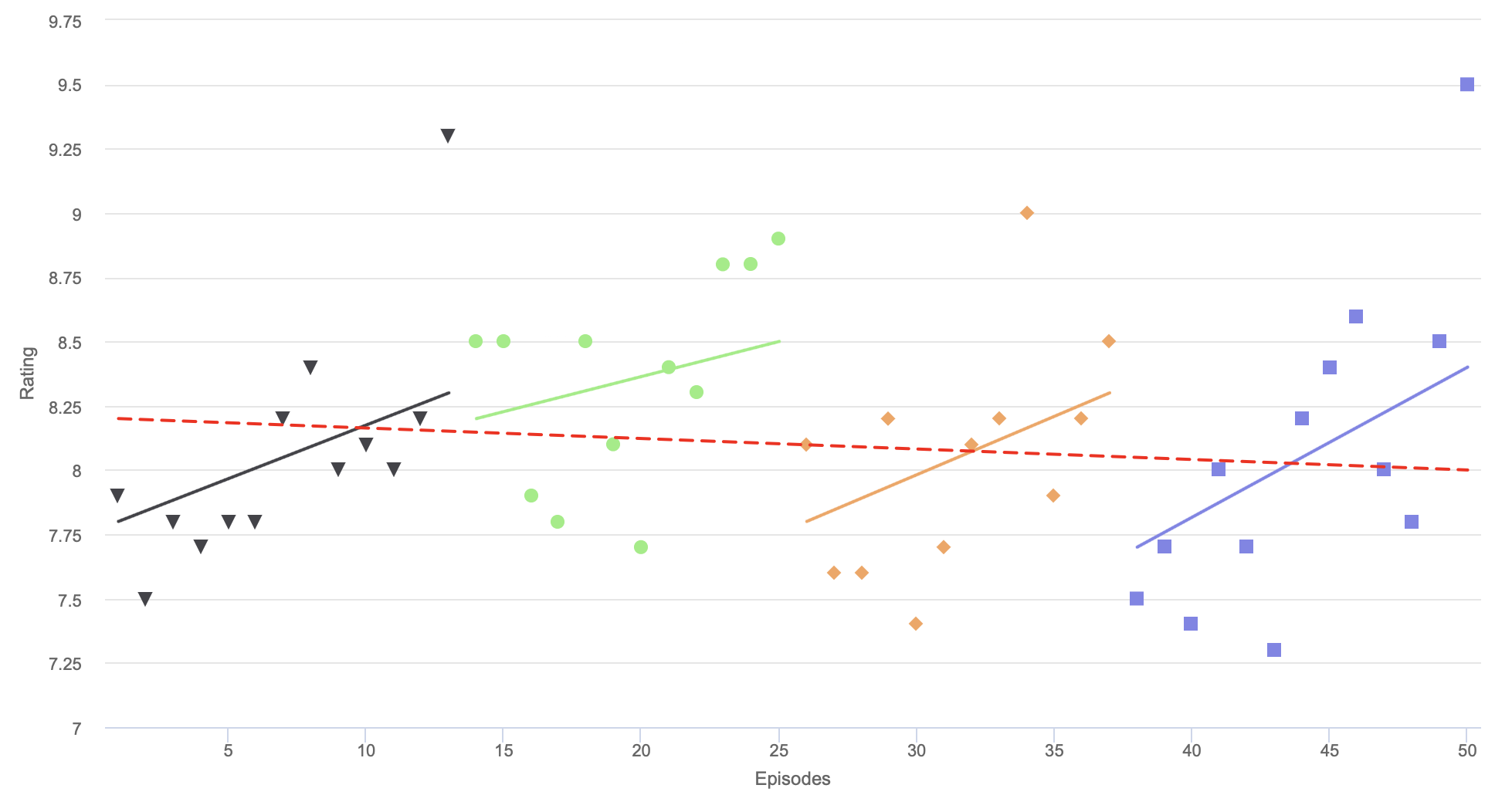

Incidentally, here's a rare case where I can literally point to data which backs this claim up. The plot of all IMDb user ratings of The Good Place episodes makes it clear that people largely can't be bothered with the openings of any season, then, halfway through—surprise, surprise—abruptly take interest again. Seasons 3 and 4 follow this pattern the most clearly, with 7 of the 10 least-liked episodes falling into those early-season plotstalls, while season 2 is the only one that partly (not entirely) bucks this trend.

It's worth pointing out that no season has a single back-half episode ranked as poorly as the season-opening episodes—the worst late-season episode, predictably from season 4's interminable slog of an ending, is still rated better than 5 early episodes from season 4, and 4 early-season episodes from season 3. - It's ironic that the surprisingly-good opening to season 2 is what dooms the rest of the show. That second season opens with a literal reboot—memories wiped, neighborhood reset, new schemes hatched—with the explicit intent of sending these characters in new directions, making them confront challenges they've never seen before. At the time, it's a delight that the show immediately confounds these expectations: the season 2 opener goes so catastrophically awry that it ends with another hard reset, and the following episode, "Dance Dance Resolution," has a great deal of fun showing just how many times these characters wind up back in the same old place.

The show eats its cake and has it too: if these characters always wind up in the same place, then it can be forgiven if they start treating each other like they've had seasons and seasons to develop their relationships with one another, each season ultimately feeding into whatever emotional dynamics we'd established the season before. But this also makes a (bad kind of) farce out of the constant reboot premises: when season 3 establishes, early on, that no change will be expected out of these characters, then all we have left is to wait patiently for the real plot development to begin, and hope that the episodes in between won't stall as atrociously as, well, they almost invariably do. - This pattern holds true even in season 4, where three of the four main humans don't have their memories wiped. It was a neat experiment to see whether or not the introduction of four new characters would make for interesting plot fodder; in another show, I think they genuinely could have. But again, The Good Place runs up against that central Schur dilemma: he so can't bear to write a show in which people aren't immediately redeemable that almost every new character's issues can be solved within a single episode, and he's so bad at writing irredeemable characters that the stereotypical "awful straight white man" he throws into the mix became the center of the show's single-least-liked episode, an interminable slog of one-dimensional shitheadedness that nonetheless ends on a "redemption moment" that's almost-entirely unearned.

- The Schur dilemma was best illustrated in Parks and Recreation, Schur's breakthrough sitcom, which continually struggled to introduce conflict for its "likable" characters or make its "unlikable" ones remotely watchable. The second season of Parks and Rec sees overenthusiastic bureaucrat Leslie Knope contend with a number of wealthy and/or corporate assholes, and lose against them every time. These episodes work in part because they are overtly unpleasant: the shitty people are conspicuously shitty, their victories make the world worse, and the "sympathetic" characters who politically align with the shitheads seem grimier and grosser by affiliation. This set up a season 3 in which Leslie Knope becomes almost superhumanly competent, saves the town, makes virtually everything better for virtually everybody, and faces almost no conflict from anybody remotely as shitty as the one-off antagonists in season 2.

And then what? Well, we have a season in which Leslie runs for office, and does a number of excruciatingly embarrassing and/or awful things in the name of keeping her relationship afloat, some of which seem like fireable offenses. But she keeps her job; she keeps her man; against all odds, she wins her election, because millionaires and slick campaign teams aren't nearly as competent or ruthless as the soda-corp executive who crushed her two seasons ago. Season 5 therefore sees her face off against a truly grody local official, unpleasant through and through; in the process, she gets recalled, because the show remembered it only loves the citizens of Pawnee when it's taken the time to thoroughly despise them.

In the meantime, the rest of the show stalls, because it has no interest in presenting its main cast with genuine dilemmas. One by one, each gets married off; one by one, each finds themselves in a stable, fulfilling adult life. Only Leslie Knope faces significant ups and downs, and all of those are arbitrary and decided upon by fate. After her painful fourth-season reversion to norm, it's decided that Unpleasant Leslie is too unpleasant, so all unpleasantness is externalized to outside forces against whom Leslie doesn't stand a chance. Until, that is, those forces abruptly fall silent, because it's been decided that Leslie ought to rise again.

Every Mike Schur character is either All-Good or All-Bad, all the time. You can flip a switch and make one character go from one to the other, the way that Andy Dwyer starts out vile before abruptly becoming the underdog, but there is virtually no grey area in between the two extremes. We can root for the All-Good ones, but they follow a relentless upward trajectory, one that lasts approximately two-and-a-half seasons at most; we can barely stand to see the All-Bad ones on-screen, because they are equally relentless in their odiousness.

Which is why, perhaps, The Good Place feels like the platonic ideal of a Mike Schur show: everyone is All-Good, except for a couple of obligatory All-Bad forces, all of whom are converted to All-Good the moment the show's decided to move onto the next plot hurdle. The plot is simultaneously swift and nonexistent: things seem to constantly move forward, and at the same time, the characters in the final episode have moved approximately half a step to the left from where they began in the pilot. - The various plot developments of the show, in order, are as follows:

(spoiler alert)

• Eleanor Shellstrop is sent to "the Good Place," despite not being very good.

• "The Good Place" turns out to be a subsection of "the Bad Place," masquerading as heaven mainly to torture her and her new friends.

• Michael, who is a demon, reboots the "Good Place" to try torturing the humans again. That fails, so Michael is forced to work with the humans in order to keep his job. In the process, Michael also decides to be good instead of bad.

• The question of whether people can get better is raised; this question is tested by resurrecting Eleanor and her human pals back on earth, to see whether or not they can improve.

• That goes awry, so instead the question becomes whether or not the "points system" is broken and sends too many people to the Bad Place.

• It turns out that "life is too complicated" for any actions to genuinely be good anymore, thanks to slave labor and sexism and whatnot, which is why nobody gets sent to the Good Place anymore.

• This results in an experiment to see whether other humans can get good in the afterlife, or whether it was just Eleanor & Pals.

• They can! This leads to a three-episode feint(???) in which it's decided this revelation maybe ought to lead to wiping out humanity, because we needed some artificial tension.

• Eventually, Our Heroes work out a new afterlife wherein people are challenged to become better. This is proclaimed as a revolutionary masterstroke, rather than one of the crudest and most ancient concepts of purgatory.

• It's revealed that the actual Good Place is in trouble too, because people are so happy there that they turn into zombies, because "happiness" here is defined by the instant-gratification society that The Good Place continually pretends to critique while indulging at every possible turn.

• The solution there is to let people, uh, die in the Good Place, when they're ready to "move on." - I insist on bulleting these out because The Good Place does an ingenious job of making each of its "twists" feel intriguing in real time, despite them falling astonishingly flat as they accumulate. Again, this is a failure of philosophy and a failure of plotting: The Good Place's fundamental failure is its unwillingness to ask what it means to be good or bad even as it pretends to only ask those questions. It will namecheck Buddhism, but it will never interrogate what it means that "happiness" in The Good Place is defined almost exclusively by material acquisition: monkeys in go-carts, instant shrimp dispensers, frozen yogurt that tastes like fully-charged phones feel. It will endlessly critique wealthy socialite Tahani's namedrops of celebrities, while joking equally-endlessly that Beyonce is a literal perfect human. It cites at least twelve philosophers' definitions of love, but its only conclusion is that love is something you make with other people—something the Beatles could sum up in a couplet.

In the end,the love you takeThe Good Place's conception of eternal life is flawed, because its conception of existence is flawed. Of course its idea of heaven seems stultifying: all it can envision is the status quo combined with relentless indulgence, just as its idea of sexual intimacy is largely just the word "orgasms" repeated again and again and again. Its early feint towards monastic asceticism is just a set-up for the joke that its "Taiwanese monk" is actually a dirtbag from Florida; the only two times asceticism is genuinely invoked, it's to show how miserable it makes people. (Tahani is miserable because her "soulmate" won't talk to her; later, Jason is miserable because his "soulmate" likes eating tofu. The monk that Jason is "mistaken" for, meanwhile, is simultaneously hailed as a profoundly enlightened human and mocked for literally "having the mind of an eight-year-old child.")

I said earlier on that The Good Place's critique of technocracy, of "algorithmic" judgments of good and bad, is incisive and clever, and I stand by that. And I'd love for The Good Place to be the kind of show where this exceedingly shallow vision of heaven simply doesn't matter, because it's obviously having fun with its zany ideas about heaven (clam chowder fountains) and hell (penis flatteners). But the show itself insists on having a plot, and on having that plot somewhat revolve around the metaphysics of this world. That plot has to carry a lot of weight, because it serves as the justification for virtually nonexistent character growth, extremely flat romantic arcs, and a series of "mysteries" that affect both the fate of the universe and purport to explain just why each of its characters struggle to be happy with themselves. - As my best friend read How To Be Perfect, she started highlighting the sentences that actually said something about "moral philosophy," however trite. The gag became photographed page spreads in which thin trickles of words stood out in yellow against endless vacuous oceans of nothingness, as ideas which could have been compelling were "buttressed" with such lengthy, nonsensical digressions that the ideas themselves began to feel like farce.

Ideas, presented honestly, are inherently compelling. Substance is stimulating. It has to be expressed in a way we can wrap our brains around, or else it's wasted on us, but we are nourished by thought, energized and sustained by the way its intricate lacework of fibers connect with and reinforce one another. The clarity of a good idea is not that it's simple, but that it's useful: a new mental muscle that helps us move through the world, letting us not only see but act. A good idea might require some sophistication, but it makes the world exponentially easier to make sense of and move through.

At its core, The Good Place has a few good kernels of ideas. You might watch it and come away a better person. That would be nice! But its affect is painfully shallow, and, because it binds its plot so tightly to its ideas, the result is a shallow show, one whose biggest emotional moments are often manipulative and crowd-pleasing and not remotely rewarding or owned. (It feigns catharsis simply by means of the old "long periods of stasis" trick: when Eleanor finally kisses Chidi, the moment has power because we've been told for two seasons that she's falling in love with him, not because the moment itself makes that kiss mean anything in the slightest.) Frustratingly, The Good Place is capable of nuanced character work in miniature: every so often, it throws out a half-hour that genuinely portrays intimacy in subtle ways, although it just-as-often throws out a half-hour that goes through the motions without affecting anything. But it leans on a Bigger Picture to afford itself substance, and that Bigger Picture just isn't very big. It's not even a glib take on a compelling subject. It's just glib. - It feels almost offensive to compare The Good Place to Enlightened, the two-season HBO sitcom in which a blonde dirtbag decides she needs to become a better person, because Enlightened doesn't deserve to have its name so taken in vain. But a comparison is illustrative.

Eleanor Shellstrop is "awful" in the sense that she is in fact charming, well-meaning, and likable. Everything awful about her can be blamed on her parents—sure, at some point we're told she shouldn't use her parents as an excuse, but the show says that and spends three subsequent seasons exploring why it is, in fact, her parents' fault. She does selfish things that are harmless, and continually struggles to do better. Everyone around her says constantly what a wonderful, inspiring person she is, including the demon who she literally inspires to become the new benevolent God. Her boyfriend works tirelessly to help her, and constantly reminds her that she's the best thing that ever happened to him. About the greatest moral epiphany that she comes to is that she should let that boyfriend move on, even though it hurts her (kind of).

Amy Jellicoe, by contrast, is genuinely awful. She hurts virtually everybody in her life, and doesn't hurt them any less when she's acting in the name of virtue. Her mother causes her a great deal of suffering, but then, she causes her mother a great deal of suffering back—and the moment when we look into her mother's life is both devastating and revelatory, in part because we get to see how wretched Amy is when you're not living in her shoes. At the same time, Amy's frustrating saving grace is that she's right: she has had a moment of genuine revelation, and she does want to make the world materially better, despite being virtually powerless to do so. When she finds a way to make a difference, it's an act of substantial self-sacrifice, one that she plows forward with knowing that the consequences will almost certainly be disastrous. She is surrounded by people who love her, or at least mean well by her, and are simultaneously afraid of her, guarded against her, oftentimes upset with and frustrated by her for extremely relatable reasons. In Amy's world, there is no heaven—and the conspicuous absence of a heaven or a hell makes the need to do good that much more urgent and perilous.

The Good Place is funny because it possesses Mike Schur's immaculate sense of comic timing, because it's colorful and ludicrous, and because it runs the classic sci-fi gag of "aliens describing humans in bizarre ways" into the ground. Enlightened is the funnier show, but it's hard to explain why. On some level, I think, it's because it's a remarkable student of human behavior, and knows how to capture the subtleties and nuances of how people act and talk and think in ways that feel immediately relatable. On another level, though, it's that Enlightened strives, over and over again, to show you the interiority of various despicable people, to make you feel what it's like to be them so deeply that it hurts, and then, just as you're full of a kind of love for them that's actively uncomfortable to feel, it makes them say the same old awful shit, tricking a startled laugh out of you as you try to reconcile the person you hope and feel and hurt for with the person who just said something almost unconscionably terrible. Which is the message of that show in a nutshell: enlightenment means loving people, not because you don't hate them or even because they don't deserve your hatred, but precisely because there will always be good reasons to hate everyone, just as you will never run out of reasons to hate yourself or be hated by everyone else. It's a show about a hateful, hatable woman that it desperately wants you to find a way to love. - In its last two episodes, The Good Place also namedrops Twin Peaks and The Leftovers as crucial signifiers of heaven. Strictly speaking, this isn't wrong, but it's painful just the same to see a show this morally facile namedrop Twin Peaks, just as it's infuriating that a show whose afterlife is this trite could bear to mention The Leftovers, arguably the most profoundly religious TV show ever made.

- Did I tear up rewatching the finale? Of course I teared up. But, just as happened the first time, I didn't tear up at the overly-grand final moments, which were a little repulsive in just how blatantly they try to tug on heartstrings the show had never reached. Instead, I got choked up at the gag halfway through, where (spoilers) Jason, who we thought was the first person to depart, reveals himself to be alive just after Chidi leaves—itself an almost-but-not-quite touching moment—and explains that he's been waiting here for eons to give his robot girlfriend the dumb handmade gift he thought he'd lost when he first "left."

Jason is my favorite part of the show by far, both because his dumb "dumbness" jokes never get old for me, and because he's the character whose moments of "goodness" are never belabored, never subjected to lengthy "wall-of-text Instagram psychology" monologues, and often presented as surprising blips of wisdom for a very stupid man—a portrayal of enlightenment that lines up with some of my favorite ideas in Zen Buddhism. (The Good Place, to its credit, makes that connection intentionally and without calling undue attention to its doing so, which is a strangely tasteful choice for an unnecessarily tasteless show.) In this moment, the thing that gets me is threefold: first, the surprise-reveal that he's alive just as another character is sent off to his emotionally-manipulative demise; next, the calm way that he explains how he simply decided to wait peacefully in this forest for the (not-a-)woman that he loves, because however many thousand years was worth this brief final moment together; finally, his last little childish "Chidi, wait up!" as he runs off into nothingness, revealing either that he still doesn't understand what's going on or—my bet—that he's the only one who does.

It feels telling to me that the one moment that genuinely struck a chord for me was presented as a joke, delivered by a joke character, and ends almost as soon as it's begun. It's almost a little koan of a moment: startling, paradoxical, and over too soon to process. In my recollection, The Good Place had a startling number of such moments; upon rewatch, disappointingly, it had a handful at best. Mostly what it had was great set design and enjoyable sci-fi worldbuilding: it's funny to me that it executes science fiction writing and filmmaking more effectively than most sci-fi filmmaking does, and helped me realize that my interest in the show was as a bit of surprisingly well-rendered genre fiction all along. (Janet, who's conspicuously the fan-favorite character, is also the most explicitly science fiction element in the show. I do not think this is coincidental.)

Perhaps that can also serve as The Good Place's ultimate defense. Science fiction has a storied history of being glib, mock-profound, and completely inert on matters pertaining to love, existence, and morality. The Good Place at least did us the favor of being glib and inert in ways that involved six really hot people wearing nice dresses and/or taking off their shirts.