Jonathan Ive, best known as Apple's chief designer over its "iMac, iPod, iPhone, Apple Watch" era, has announced that he'll be building a new tech product for OpenAI, along with a team of extraordinary hardware and software developers. Suffice it to say that I feel... conflicted... about the announcement.

On the one hand, Ive is an incredibly talented designer, and a phenomenal director of talent. (And his team includes some of the best people who've ever worked for Apple, including Mike Matas on the software team and Evans Hankey on the hardware team.) You could argue that Ive's new team is better than any single team that Apple has ever seen.

On the other... OpenAI, and particularly its CEO Sam Altman, are about as hacky as Big Tech gets—and Big Tech is famously a pretty hacky industry. Altman has made a career out of overpromising and underdelivering. AI has perfectly suited him, in that it's a product that delivers "results" that are too nebulous and open-ended to easily assess or critique—but it demonstrably has some pretty serious flaws that are likely insurmountable, and is being promoted as capable of much, much more than it both can do and ever will do. It's a fascinating combo of technical breakthrough and snake oil, and the industry as a whole is built far more around the snake oil than around the technical breakthroughs.

The most intriguing claim that Ive and Altman make, in their product reveal video, is that it's time for a new tech product to replace the phone: a new form factor, perhaps, and a new way of interacting with computers as a whole. This is simultaneously an intriguing and a disturbing premise to me—and it's one that's been made more and more. But importantly, I don't think it's true.

I've been chewing on this as I processed some related industry news: namely, that The Browser Company has discontinued building Arc, a modern web browser that I've become quite a fan of over the last few years. Arc is a marvel of user-interface innovation: it's introduced a number of features to the web browser that, frankly, I no longer want to do without. So I was understandably distressed to read CEO Josh Miller's explanation of why The Browser Company is abandoning Arc to develop a new AI-centric web browser:

On the one hand, Ive is an incredibly talented designer, and a phenomenal director of talent. (And his team includes some of the best people who've ever worked for Apple, including Mike Matas on the software team and Evans Hankey on the hardware team.) You could argue that Ive's new team is better than any single team that Apple has ever seen.

On the other... OpenAI, and particularly its CEO Sam Altman, are about as hacky as Big Tech gets—and Big Tech is famously a pretty hacky industry. Altman has made a career out of overpromising and underdelivering. AI has perfectly suited him, in that it's a product that delivers "results" that are too nebulous and open-ended to easily assess or critique—but it demonstrably has some pretty serious flaws that are likely insurmountable, and is being promoted as capable of much, much more than it both can do and ever will do. It's a fascinating combo of technical breakthrough and snake oil, and the industry as a whole is built far more around the snake oil than around the technical breakthroughs.

The most intriguing claim that Ive and Altman make, in their product reveal video, is that it's time for a new tech product to replace the phone: a new form factor, perhaps, and a new way of interacting with computers as a whole. This is simultaneously an intriguing and a disturbing premise to me—and it's one that's been made more and more. But importantly, I don't think it's true.

I've been chewing on this as I processed some related industry news: namely, that The Browser Company has discontinued building Arc, a modern web browser that I've become quite a fan of over the last few years. Arc is a marvel of user-interface innovation: it's introduced a number of features to the web browser that, frankly, I no longer want to do without. So I was understandably distressed to read CEO Josh Miller's explanation of why The Browser Company is abandoning Arc to develop a new AI-centric web browser:

Electric intelligence is here — and it would be naive of us to pretend it doesn’t fundamentally change the kind of product we need to build to meet the moment.

Let me be even more clear: traditional browsers, as we know them, will die. Much in the same way that search engines and IDEs are being reimagined. That doesn’t mean we’ll stop searching or coding. It just means the environments we do it in will look very different, in a way that makes traditional browsers, search engines, and IDEs feel like candles — however thoughtfully crafted. We’re getting out of the candle business. You should too. [...]

Webpages won’t be the primary interface anymore. Traditional browsers were built to load webpages. But increasingly, webpages — apps, articles, and files — will become tool calls with AI chat interfaces. In many ways, chat interfaces are already acting like browsers: they search, read, generate, respond. They interact with APIs, LLMs, databases. And people are spending hours a day in them. If you’re skeptical, call a cousin in high school or college — natural language interfaces, which abstract away the tedium of old computing paradigms, are here to stay.

To the best of my knowledge, Miller is a smart guy: he seems straightforward, intelligent, and perceptive in ways I'm not willing to credit Altman with. And he makes a lucid, thought-provoking argument here: namely, that both browsers and webpages aren't fluid enough to be effective at their tasks, and that AI offers an addictive fluidity. Hence the appeal of the "chat interface," in which any open-ended prompt can deliver unique, robust results.

Like Miller, I too know quite a few people who use ChatGPT on a daily basis. And I completely understand why they do. More than anything, contemporary AI products replace Google and related search engines, which were the "blank slate" apps of the Web 2.0-era Internet. You entered a search prompt, and Google returned whichever kind of web site gave you the kinds of information or functionality that you were looking for. As time went on, Google introduced "infoboxes" to create even more fine-tuned information: a weather display if you ask whether it will rain tonight, showtimes for movie names, shopping options if you search for chinos. AI functions as a kind of free-form infobox, capable of generating any relevant information for any kind of query.

Miller's argument is that, basically, this is the future of the Internet, and of computing in general. You'd be silly not to at least stop and ask whether he's got a point. And, leaving AI aside, we've already seen computers take steps towards offering this kind of experience. The initial idea behind Siri—as executed better by Alexa and Google Assistant—was that you could operate your own devices via voice, without bothering to navigate through individual app interfaces. I've written myself about how liberating this can be: about how exciting it is to liberate the act of computing from any individual form factor, accessing a central pool of functionality and knowledge in a fluid variety of ways. AI isn't even the first "everything bucket" that computers have tried to offer us: Wolfram Alpha, which Siri has had access to since day 1, tries to offer an index of every kind of knowledge in the world, accessible via—you guessed it—open-ended text prompt. (It's unsurprising that it now offers a "WolframGPT" format.)

One way to think of AI is as a nexus of these two things: computational fluidity on the one hand, where you can access programs and function without being specific about it; and informational fluidity on the other, where virtually anything you want to know is available upon request (in whatever format you desire). Josh Miller sees this as the future of the Internet, and subsequently as the future of web browsers: why access something like ChatGPT via a web site, when your browser can just do all the thinking for you? And Sam Altman and Jony Ive go a step further, and think of this as the future of all computing: why bother with a phone, or with apps, when your computer can do all the computing on its own?

For a moment, let's leave aside the ethical questions about AI; let's leave aside the question of whether AI will ever deliver a reliable, functional product; let's avoid the philosophical questions of whether we need technology to be even more of a black box, in an age where consumers are increasingly disempowered already. Instead, let's just ask: is this what the future of "using a computer," or "browsing the web," ought to look like? Does a product like Josh Miller's, or a product like Sam Altman's, really give us a superior version of what we want to use computers for?

And it's easy to see a world in which the answer is "yes"—which is that intriguing and disturbing premise I mentioned earlier. Because our phones aren't the digital paradises, or the hyperefficient tools, that we imagined they might become back in 2007. Web browsers, and the Internet at large, are at the very least dysfunctional, if not outright dystopian. Jony Ive, who for a while managed both hardware and software design for the iPhone, has had more of an opportunity to "fix" our devices than anybody else alive. Josh Miller, who delivered us an interesting web browser after literal decades of stagnation, has thought more about the Internet than most other people ever have cause to.

The easy, obvious appeal of AI is that it's a release from "apps" and "browsers" and "web sites" as we've come to know them. All the frustration, all the stodginess, washed away, replaced by a deceptive simplicity. No need for specialized apps or interfaces, be they digital publishing platforms like Wordpress or specific planning and productivity tools: just let AI figure out the finicky bits for you, and focus on telling it what to do.

And as far as blank slates go, it's hard to say we've ever had a better one. Google was never as open-ended as a ChatGPT prompt is—and that was before Google went as downhill as it got. The iPhone's original interface was iconic... but the experience of starting with a new iPhone from scratch, and of hunting down the dozens of applications you might need on yours, is a considerably more painful prospect. So if this kind of blank-slate prompt-driven experience is really what we want computers to be—if this handles what we use computers for better than any other approach to interface design—then we might just be looking at the future of computing.

But I don't think that blank-slate UX really is what computers do best, or even how we want to use computers. Google used to be a last resort—the thing you turned to when you didn't have a better resource. The App Store was, ideally, a place you visited as infrequently as humanly possible. And while voice agents are great for simple mechanical demands, and for basic information retrieval, their utility is limited for reasons beyond mere lack of fluidity.

A well-designed, precise interface is always going to be more appealing, more enjoyable, than something that strives to be as aimlessly general-purpose as possible. Because what computers are best at—what makes the best computing experiences so compelling—is specificity. What we've lost, more than anything, over the last 10-20 years is particularity. And AI doesn't feel like a solution to the real problem that we're facing: it feels like the same old problem masquerading as a solution, when in fact it makes the faults in our computers worse.

If I had to hazard a guess, this is why so many people are so viscerally opposed to AI—more than their issues with it infringing copyright, or getting facts wrong, or even threatening people's jobs. AI is a general-purpose tool intended to erode more precise tools' functionality. People loathe the AI box atop Google results, not just because it's frequently wrong, but because it's another reduction of their computing experience to so much lukewarm pulp.

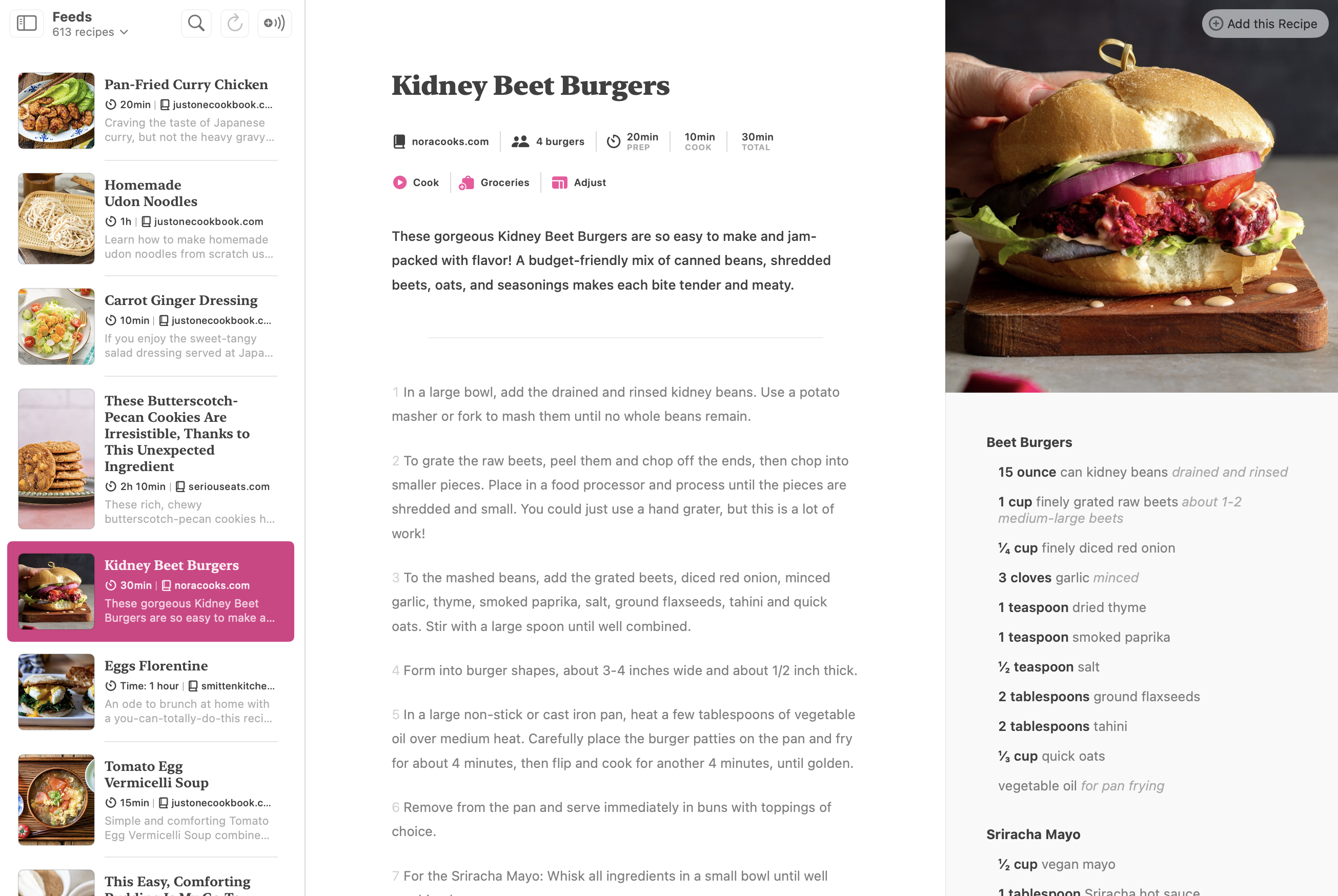

Perhaps my single favorite app these days is a cooking app called Mela. Virtually every friend who I've introduced it to has bought it—that's right, bought it, in a day and age when people allegedly don't buy things anymore. It's hard to see Mela in practice and not want to use it: it's gorgeous, it's useful, and it offers a slew of functionality that other apps never thought to introduce. Mela doesn't just offer you a way to download any recipe on any web site without having to reformat it: it also lets you subscribe to recipe blogs, turning your respective subscriptions into a living cookbook. It also lets you scan the pages of physical cookbooks and easily digitize their contents. And it offers a variety of interface varieties, from a grocery manager to a full-screen live-cooking mode with multiple live timers and easy references to the ingredients in the various components that you're making.

What makes Mela so compelling is the way it blends clever computing tricks with thoughtful human-first design. It handles the entire process of cooking, from discovering recipes to buying groceries to making what you want to make. What's more, it makes all of these steps easy: the combination of its blog-subscription functionality and its recipe-formatting magic means that, if I'm hunting for new things to cook, I have a literal live feed of new things to try from chefs that I enjoy, presented so meticulously that I can start cooking a recipe I've never seen before with a single click.

Isn't that just great? I didn't have to format a single thing.

It's possible to imagine an even better app than this, of course. For years—a decade this July!—I've found myself returning to this post by Neven Mrgan about his favorite cookbook's data design: among other things, it offers planning instructions to ready a given meal, that meal's flavor profile (along with suggested pairings), and information on how to store something once you've already cooked it. Of course, some of this data requires an actually-experienced chef who knows how to give you this information... but imagine a recipe publication platform that gave people easy ways to publish this information, if they happened to know it. The interface for creating things matters as much as the interface for consuming it, after all.

Can I imagine room for a chat interface in an app like Mela? Sure—just like I can imagine expanded functionality, like an "available ingredients" tracker that monitors what I've already stuffed in my fridge. "What can I cook today?" would be a useful prompt for an app to be able to answer. Or: "Do I have any recipes for a quick-to-make vegan dessert?" I'm not opposed to natural language processing making sense of the data in my apps, as Josh Miller suggests, just like I'm not opposed to natural language prompts as a form of interface. But I can't imagine wanting an AI-powered device replacing Mela's interface, because Mela's interface is already close to perfect. I wouldn't want to use another cooking tool—I already have exactly the one I want.

In other words, I can imagine scenarios where I'd want AI augmentation on top of an existing app. But that's different from wanting to replace my existing apps with an AI-centric solution—and "AI augmentation" is just not a lucrative enough opportunity for the tech industry to care about pursuing it. Not when they're shouting revolution, revolution, revolution all the way.

Let's look at another, more omnipresent type of app: email. I'm writing this newsletter, as I always do, in HEY, which also happens to be the tool I use to handle all my emails. Like Mela, HEY is a fantastic example of a group of people flat-out inventing cool new ways to take care of common email problems: unlike virtually every innovation Google's ever tried to stuff into Gmail, HEY has actually succeeded in getting me to like email again. Email via HEY is simply a different experience than email via any other app.

How does AI fit into a hypothetical email workflow? Google has long touted Google Assistant's ability to read and reply to emails through voice alone. Fine, that's nice. Apple advertised—and later got in trouble for advertising—an "Apple Intelligence" pipeline that would let you, through a single voice command, find an attachment in an old email of yours, save it to your photos, crop it, and send it out to somebody else. Cross-app functionality, in other words—the kind of thing that makes individual apps a bit less important, as AI advocates love.

And again, these features are nice! But they're somewhat superficial examples of functionality, whereas what makes HEY so compelling is that it offers unique interfaces for different types of emails, specialized workflows for screening new senders and replying to different people all at once, ways of conveniently storing messages for later, and even ways of reading newsletters as a combined publication of sorts. I don't need a chat-based prompt for any of this; I don't need an AI system to "manage" my emails for me. The best interface for HEY is the HEY interface. And while there are plenty of aspects of HEY that I'm critical of, those are improvements that I'd like to be added to the app itself—improvements that would push it further away from the realm of computing that AI handles best.

The irony here is that I'd cite Josh Miller's own Arc as one of the best apps I've used in recent memory. Arc has been terrific in the same ways that HEY has been: namely, it's inventive. It stores tabs differently than other browsers, offers unique ways of viewing different sites simultaneously, and continually adds new little tidbits that make my use of a web browser more convenient and more delightful—things like hover-to-view-new-emails functionality on any Outlook tab I have open. Just like HEY has completely changed how email works for me, Arc has (somewhat-less-)completely changed how I approach web browsing. Its specificity is what endears it to me more than anything.

And the dirty little secret is: Arc has, bit-by-bit, incorporated AI functionality over the last year and change. And almost all of its AI improvements have been... pretty mid. I've given them all a trial run, and I've disabled virtually all of them. The one I do like—a tool for automatically organizing tabs into groups—is a smart, thoughtful use of LLM-powered intelligence... but it's nice because of how already thoughtful Arc is when it comes to grouping tabs. And to be honest, Arc could have done a better job developing a grouping interface, at which point I'd barely use its one good AI feature at all.

The Browser Company also offered an alternate vision of Arc in its iPhone app, which revolves primarily around an AI prompt interface. I toyed with it once or twice, then deleted the app off my phone altogether. Contrary to what Miller claims, I don't want an AI layer to do my browsing for me: I just want a better browser. Yes, sometimes an AI prompt might find me quicker results than Google nowadays, because Google's gotten pretty awful. But I'm not going to switch to Arc or to ChatGPT over that: I'm going to start using Kagi, which solved Google's problems by offering a better search engine.

That said, I'm sympathetic to what Miller says about his team's difficult conclusion that Arc is too incremental a change to really be revolutionary. I've long been fascinated with web browser design, because I've long felt that web browsers are among the most difficult apps to design in the first place. The Internet is a wild, cluttered, messy place: only in a place as dysfunctional as the Worldwide Web would you ever need a search engine—itself a pretty damn inefficient solution to an open-ended problem—to begin with. Tabs accrue like weeds. Focus continually splits. Different web sites exist on drastically different scales, not in terms of their popularity but in terms of their functionality: a blog post is tinier than a publication, a publication is smaller than a social network, and how do you even begin to make sense of a user's browsing tendencies as a series of parallel processes, with different tabs and sites belonging to different activities? Most of the solutions we've seen—like Safari's "tab groups"—are great in theory, but frustrating in practice. A better web browser would have to be more intelligent about deeply answering the question of what, exactly, people do when they browse the web.

But from what I've seen of Dia, which The Browser Company is replacing Arc with, it doesn't seem to have answers to that question. In fact, it doesn't seem to have asked that question to begin with. Dia proposes a continual relationship between AI agent and web site: generate timestamps for this YouTube video, summarize this article, generate an outline based on these notes. That stuff's neat, if you overlook the various (and highly meaningful) critiques of trusting AI to do stuff like this—but it doesn't deeply engage with that central question of how people browse the web. What are people looking to do on it? And how do you give them the best tools for doing what they want to do? How do you make reading better online? How do you make interactions better? How do you help people make sense of the endless glut of Everything That The Internet Is, both within the constrained silos of various social networks and in the broader, often-forgotten landscape of the Internet as a whole?

What does the app do, in other words, beyond providing a generalized prompt-based interface? When I look at the several hundred tabs I've got saved in Arc, many of which I never come back around to, how do I make sense of the things I was aiming to accomplish with my time online? How do I find a sense of purpose? And how does a browser go about helping me do that while also encouraging the Internet at its best, which is to say its wilderness, its weirdness, its general sense of possibility?

Dia's vision, and (more broadly) the AI industry's vision, is: reduce it. Shrink it down. It's too much. There's too much cognitive overload, it's too confusing, it's too hard to make sense of it, so just get rid of it. Go in the opposite direction of Neven Mrgan's beautiful cookbook: let's just give people tools that let them stop having to think about it in the first place. Which is the opposite of what I want the Internet, and web browsers, to be.

When I think of the Internet, I think of Neal.fun, with all its playful little takes on what the Internet (and computers) can be, and of Jon Bois's masterpiece 17776. I think of Andy Baio's link blog, which consistently finds the most Internetty parts of the Internet and offers them up to the rest of us. I think of Defector, a publication whose writers have such strong and compelling voices that I know each of them by name; it's the one publication I can't read via an RSS feed, because of how much of the site's experience involves browsing through its grid of punchy article names, noting which individual wrote each piece. I think of the SCP Foundation, and its endless sprawling hard-to-keep-track-of horror stories. I think of unique experiences.

Similarly, when I think of a site like YouTube, I'm not really thinking of them in terms of publication mediums, or in terms of content creation. I'm thinking of the insane technical minutiae and dry-yet-compelling presentations of pannenkoek2012's Super Mario 64 breakdowns. I'm thinking of Lasagnacat posting an unhinged hour-long lecture about a single three-panel Garfield strip. I'm thinking of the first time I watched Too Many Cooks, or—hell—Gangnam Style. I'm thinking of unique experiences, and of the kinds of thing that literally can't exist anywhere but the Internet. (I still rewatch Vine compilations on YouTube, because Vine was an entire unique online medium whose entire existence is now compressed into longform YouTube remembrances.)

Even when it comes to more "productive" tasks, I remember specific experiences—specific products—more than anything else. I remember checking The Cool Hunter in college, wondering if I'd learn new things about style and fashion and culture. I was obsessed with The Wirecutter before it was bought by The New York Times, back when its approach to product reviews was radically new and not just the new norm. I still frequently mourn the loss of Hipmunk, which was the single best way to find good flights, and whose demise left a hole in the world that may never be filled.

I'm endlessly interested in digital ritual: the ways we construct processes, habits, and culture. Whenever a new season of Survivor airs, I have a tradition every Thursday morning of checking the same three Reddit threads, the same Entertainment Weekly recaller, the same post-episode podcast. How do you create a browser (or an app) that delineates rituals like that? How do you build a product around particularities, rather than around smoothnesses? How do you honor the potential of the Internet, rather than obliterating it? How do you create something that understands the meaning of web browsing, in the same way that HEY understands the deeper meaning of how we use email, or Mela understands the deeper meaning of how we make food? And—if you'll forgive my asking a rude question—how thick do you have to be to convince yourself that AI is the solution to any of this? Sure, incorporate AI techniques into a more-precise workflow if there are things that an LLM can handle well, but how on earth do you reach the conclusion that more AI will somehow magically solve all the problems that we have with technology today?

To move away from The Browser Company—whose Dia, I hope, will genuinely be smarter and more careful than its early preview suggests—back to Jonathan Ive's ambition to create a new product that replaces phones: how do you look at the modern smartphone and think that that's the thing you have to do away with? The modern smartphone is, if anything, as close to the Platonic ideal of a computer as we've ever seen. It fits in your pocket; every millimeter of it adds something functional; it's a remarkably fluid computing environment, and a remarkably specific one, all at the same time. If anything, the existence of my phone is why I appreciate how non-general-use all of my other devices are: my headphones, my watch, my Playdate. (The only device I love more than my phone is my iPad Mini, which is really just a slightly-bigger phone with a stylus attached.) Why would I want to replace this with, well, anything else?

The only reason why I'd even imagine getting sick of my phone—and the reason why I know a handful of people who've abandoned smartphones for flip phones again—is, well, its software. People aren't sick of their phone. They're sick of their apps.

And can you blame them? Our apps are largely dogshit. They're endlessly intrusive, pestering us with notifications (and frequently designed to interrupt our trains of thought and keep us hooked). They violate our privacy, degrade our social connections, and reduce the quality of our interactions with the world around us. They're just not very good. I mean, if you think our web browsers are lousy software, just try using our social networks. Try playing modern games, the most popular of which are often the ones that are designed to literally addict us and drain our wallets. (Don't worry! They'll be replaced with sports betting apps soon.) They encourage listlessness and ennui, when they're not actively stoking our anxieties. They're just not good things, and they don't offer us good experiences, and a lot of us have noticed and are getting sick of it, really.

But it's ludicrous to think that the solution to that is to get rid of our phones. What we need are better apps. And better apps are possible. Better experiences are possible. We just struggle to get rid of the old things until newer and better options present themselves.

Similarly, while Josh Miller seems like a smart and thoughtful guy, and while I understand where he's coming from, I think he's dead wrong. Sure, he's right that Arc never thought deeply enough about the problem that it was trying to solve—but I think that the inadequacies of thought that led to Arc have only gotten worse with Dia. The people who loved Arc for being Arc are going to hate Dia for being Dia—and I just don't think there's a market for Dia outside of the Arc-lovers who The Browser Company is now alienating. I think The Browser Company is fucked, and I don't think that Miller's claims are ultimately as insightful as they seem. I think they're cowardly. They're a spineless attempt to play along with an overblown modern trend.

Sure, college students might use ChatGPT for hours a day. They used MySpace too. And if your main pitch for AI representing a brand-new paradigm is that it's a better version of SparkNotes... man, who gives a shit? I care about that as much as I care about the fact that it lets me draft an email to my boss telling him I've got bad diarrhea: claiming that it saves me a little bit of work while doing the dreariest thing in the world isn't exactly selling me on it. I'd rather someone fix tedious workplaces than fix emailing tedious bosses.

(What's more, AI really isn't as much of a new paradigm as it pretends to be. It has obvious successors on virtually every front. Yes, it does what its precursors did better, but there have always been text summary apps, there have always been bullshit generators, and there have always been robots that were willing to pretend they were your girlfriend. It's neat that it combines all these functionalities and adds more, but its only "killer app" is its general-purpose-ness—and there's no evidence that customers care, really, unless it's both a novelty and completely free.)

I do think that we're due for a paradigm shift in computing. I'm just not convinced that that paradigm shift is technical. I think we're due for a social shift in how we use computers, and in how we want our computers to work for us. We've spent twenty years watching tech companies increasingly make our products worse, in the name of exploiting us as customers, and people are increasingly sick of it. But the solution we're looking for already exists. All we need now are developers who care about making the products that we want to use.