The first Apple Intelligence features debuted at this year's WWDC keynote were genuinely captivating. Designing a semantic protocol to let on-device LLMs conduct complex inter-app operations? Incredibly useful and neat! Building cute little emoji on the fly? What a clever, considerate application of LLMs, taking advantage of their strengths and minimizing their many weaknesses. Making Siri actually understand what you're saying? I mean, I'll believe it when I see it.

Then came the interim phase: tools for rewriting text in various tones, and image generators that draw "sketches" on-the-fly. These dip their toes into slightly grody waters—in terms of both the ethics of how LLMs were "trained" to do these things and the quality that LLMs are capable of producing—but, at the very least, they're circumscribed applications that serve limited, specific purposes. Sure, the LLMs seem to generate bad prose and vapid imagery, but plenty of people do that too. If you're going to force people to produce endless heaps of bullshit for their day jobs, in the form of corporate emails and what-have-you, then why not have a machine do it for you? We're talking about dreary, mechanical work as-is.

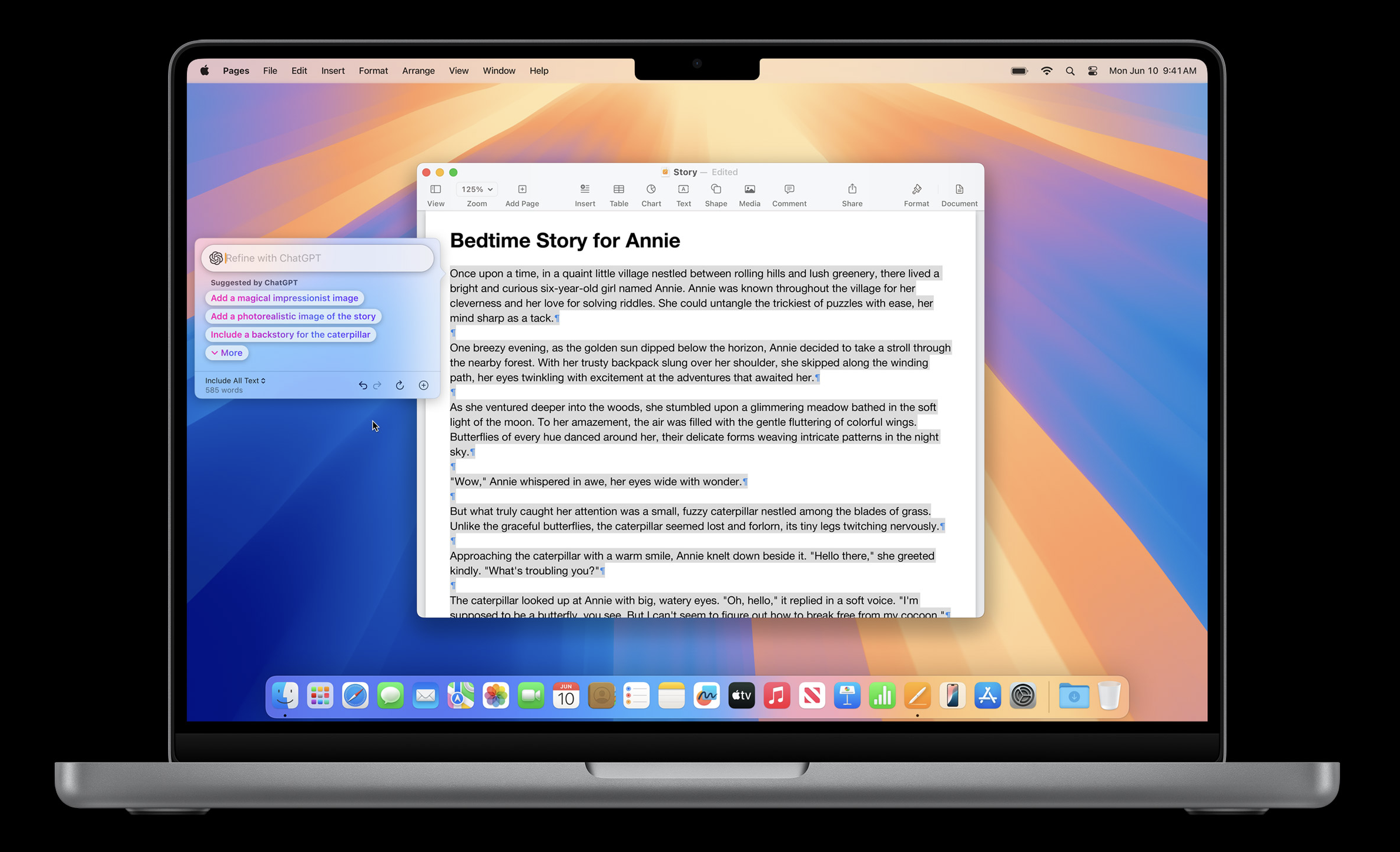

But Apple had to take it further. It wasn't enough for them to demonstrate a complete OS-level integration with ChatGPT: they had to demo it by showing a father generating a bedtime story for his daughter. Because that's the dream, isn't it? Replacing even the smallest, silliest, most intimate creative act with a grotesque imitation of it?

The "grotesque" part, to be clear, has nothing to do with the fact that a computer generated it. Chess and Go players have commented on how fascinating it is to play against unbeatable computer opponents—how unpredictable and insightful its moves can be. Computer-generated experiences can be moving, startling, delightful, ridiculous, sublime. Procedural generation is, in and of itself, a fascinating field which can, when used carefully and correctly, yield extraordinary things. No: the grotesque thing about this story is that it's dogshit. I have seen eight-year-olds write with more consideration, color, and verve than LLMs are capable of generating.

Because LLMs are designed, literally, to seek the lowest common denominator. They search for the most plausible of all possible outcomes: that which probabilistically seems like the "sturdiest" construct, if you will, where every sequence—every word, every sentence, every moment—is that which was most likely to follow the one before it.

The result, once you get used to it, is startlingly easy to detect. LLMs love padding their text. They'll never use one word where five will do. They include every possible clause in every possible sentence; they'll provide supporting architecture for every minor detail. The work they do is safe—you know, except for the part where it's inherently

I don't understand LLMs' image generation processes as well as I understand how they generate text, but I suspect that the off-putting hyper-realness of their image styles is a byproduct of a similar overcaution. Nothing can be left to the imagination. Everything must be detailed, and detailed, and detailed again, until it looks like it's been freeze-wrapped. That detail doesn't keep LLMs from getting imagery hideously wrong—it just means they try their hardest to make everything they generate, whether blandly accurate or hilariously off-base, scream at you about their realness. As Caroline Collingwood sniffs at her new son-in-law in Succession: “Gosh, look at you. You're very plausible.”

There's nothing wrong with a machine that tries and fails to do something. Some of the most intriguing things machines do involves their fucking up. (My favorite LLM creation to date, Unlimited Steam, tried to generate variations on a single well-known Simpsons scene ad nauseam; it's good because it's terrible, and because, watching it step on rake after rake, you can always discern the logic by which it arrived at its latest godawful result.) Similarly, technology is often crude; technology sometimes fails; technology frequently has far steeper limitations than it initially seems to; and all of that is fine, because we can work out for ourselves how to responsibly incorporate these technologies into our lives.

What's incredibly dispiriting, though—what's figuratively and literally dehumanizing—is when these technologies are advertised as miracle cures, to the sorts of people too ignorant to notice that they're snake oil. Promoting "Apple Intelligence" as a great tool for writing bedtime stories for your daughter? That's only going to convince the kind of person who can't tell the difference between the story in that screenshot and... literally any other prose, ever. It targets people who are in some way bereft, and it hits 'em with the sleaziest sales pitch there ever was: "You don't need to worry about what's missing." Hell, you'll never even notice it was gone.

For the last fifteen years, I've been obsessed with a specific flavor of cultural bullshit: the kind I sometimes call "crude simulacra," the kind that masquerades as something without fully understanding what it's masquerading as. It's "gourmet" chocolates at RiteAid. It's pretense without intellect, culture, or taste. It's convicted felons claiming to be billionaires. It's insidious, not just because it's fake, but because it takes the place of something real—usually without many people noticing what's gone missing.

What's frustrating about LLMs is that, given what they genuinely are good at, you could conceivably build one that's better at recommending existing bedtime stories than anything else in the world. Feed a computer data about every short story ever written, and LLMs will be able to parse that information enough to find you something weirdly perfect for what you want to read. Hell, feed it something like The Types of the Folk-Tale, which attempts to classify every narrative beat and every quality of every folktale ever written, and see whether it can use that to find something to your liking. We are awash in fascinating, beautiful, shocking information, and we've never had better tools to make something of that information with. Instead, we steal a million copyrighted books so we can make machines spit out meaningless slop. All it would take to make better things is giving a shit, but that can't make you a billion dollars, so none of the people we let make businesses bother.

"Not caring" is increasingly the hallmark of every publishing medium on the planet. Even before Spotify let itself get overrun with LLM-generated mush, its algorithm pushed so much repetitive nonsense on its listeners that entire genres sprung into being, each one defined by how little it asked its listeners to notice what was playing. Netflix infamously generates and cancels shows at a brutal clip, forcing its creators to tailor-make "content" according to what Netflix thinks makes viewers tune in. Game designers increasingly steal design cues from casinos, focusing on ways to distract their own players (because distraction makes it harder to remember you were leaving). The realm that was once defined by human ingenuity has increasingly been dominated by inhuman apathy.

Of course, we'd be remiss in overlooking Amazon's part in all this. Amazon, the original business that reduced products into "content," has long been known for recommendation algorithms that suggest you buy a stove right after you bought another stove. It was bad at moderating knock-offs before companies started spitting out LLM-generated products left and right. (Jenny Odell wrote a fascinating story several years ago about tracing some of the generic Products back to their actual creators, and realizing just how many layers of artifice lay between them and anything resembling "the truth.")

And it wasn't just Amazon that purveyed this particular flavor of bullshit: it's been ages since one of the best designers on the planet left Google for forcing him to test 41 different shades of blue. Silicon Valley has long been suspicious of the idea that a human might know anything, or have anything of meaning to offer up—it disrupts, it monopolizes, but it doesn't always seem to remember why. It preaches revolution... but a revolution of what, exactly? What will be left, when the rubble clears, and why would we trust known rubble manufacturers to know the answer?

The miserable irony is that Steve Jobs, for all his faults, was a staunch advocate for human creativity. Apple has infamously struggled with anything involving "artificial intelligence," in part, because of its weird insistence on respecting its customers' privacy; it's never been great at algorithmic recommendations, because its specialty is designing interfaces and functionality around conscious user choice. Its fledgling social networks all failed because Apple tried to make them substantial, and forgot to make them addictive. Apple Music, long an also-ran compared to Spotify, boasted about letting Trent Reznor oversee its design; its flagship feature is radio stations manned by musicians, DJs, and enthusiasts, and it brags about things like "editor-curated playlists."

(Just today, Tim Cook bragged about how Apple TV+ produces the most critically-acclaimed movies and TV shows of any network in existence. No less than Ben Stiller has talked about how surprisingly good Apple is at trusting its creators, and at putting the creative process first.)

Of all the Big Tech companies, Apple remains the one that most unnervingly seems, at times, to care—and not just about one thing, but about many things. It's the last major tech company to leap into "AI," and it took pains, today, to use more accurate phrases like "machine learning" to describe what it's been building. (The phrase "artificial intelligence," to the best of my recollection, wasn't spoken once.)

And what's frustrating is that Apple clearly does care, on some level. Its LLM implementations run from Apple devices themselves, unlike every(?) other company's cloud-based products. Apple took pains to emphasize the stringent ways they keep their users' privacy safe—this in the same month that Microsoft over-enthusiastically released an LLM-based OS feature that would have been the biggest security breach in modern software history. The way they unveiled "Apple Intelligence," too, made it clear that they think LLMs have the most utility in certain narrow-focus situations: places where a little pattern recognition, paired with a sophisticated semantic intelligence, can go a shockingly long way.

It makes sense, given the ways in which Apple relies on ChatGPT for executing certain more-complex functions, that Apple decided they might as well bite the bullet and include all of ChatGPT in their new operating system—the ersatz recipe generations, the "knowledge base" that will no doubt go viral for proudly parroting incorrect facts, and, yes, the world's worst author of bedtime stories. From the sounds of things, it will be possible to use the interesting functions that Apple Intelligence provides without having to touch upon the gross functions, which in and of itself shows more restraint and self-awareness than any other tech company to date.

But it's still infuriating. Because Apple, as a company, has generally committed to what Steve Jobs once referred to as the intersection of technology and the liberal arts: that is, technology augmenting culture, rather than replacing it. The "bicycle for the mind," to borrow another classic Jobs term. The tool that helps us open doors we never could have opened otherwise. Now it's openly bragging, instead, about a Road Runner-esque door that's been painted on the side of a rock. Who needs portals to everywhere when you could just stay nowhere instead? Who needs real things when you can have things that look like real things instead?

This is not Apple's first misstep by any means. And Apple has historically done a decent job of course correcting—eventually. But this was a gross moment during a gross period of time. What sucks more than anything is how close they came to realizing what they didn't have to do.