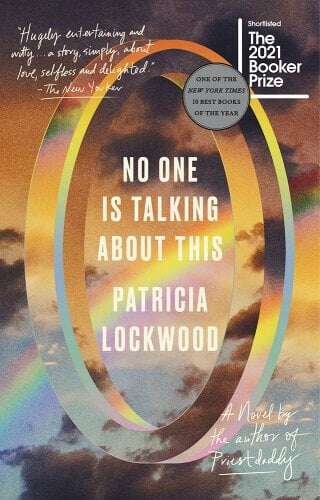

Sometimes I have trouble putting into words how much I loved No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood. It's as if she can read the zeitgeist and is just writing it down.

The best I can do is share a few quotes from the book. Here's 40. Hopefully by the time you get to the end, you've concluded that you should read it too.

Why did the portal feel so private, when you only entered it when you needed to be everywhere?

Politics! The trouble was that they had a dictator now, which, according to some people (white), they had never had before, and according to other people (everyone else), they had only ever been having, constantly, since the beginning of the world. Her stupidity panicked her, as well as the way her voice now sounded when she talked to people who hadn’t stopped being stupid yet.

It was a mistake to believe that other people were not living as deeply as you were. Besides, you were not even living that deeply.

Something in the back of her head hurt. It was her new class consciousness.

Every day their attention must turn, like the shine on a school of fish, all at once, toward a new person to hate. Sometimes the subject was a war criminal, but other times it was someone who made a heinous substitution in guacamole.

There was a new toy. Everyone was making fun of it, but then it was said to be designed for autistic people, and then no one made fun of it anymore, but made fun of the people who were making fun of it previously. Then someone else discovered a stone version from a million years ago in some museum, and this seemed to prove something. Then the origin of the toy was revealed to have something to do with Israel and Palestine, and so everyone made a pact never to speak of it again. And all of this happened in the space of like four days.

Every country seemed to have a paper called The Globe. She picked them up wherever she went, laying her loonies and her pounds and her kroners down on counters, but often abandoned them halfway through for the immediacy of the portal. For as long as she read the news, line by line and minute by minute, she had some say in what happened, didn’t she? She had to have some say in what happened, even if it was only WHAT? Even if it was only HEY!

Our mothers could not stop using horny emojis. They used the winking one with its tongue out on our birthdays, they sent us long rows of the spurting three droplets when it rained. We had told them a thousand times, but they never listened—as long as they lived and loved us, as long as they had split themselves open to have us, they would send us the peach in peach season.

Previously these communities were imposed on us, along with their mental weather. Now we chose them—or believed that we did. A person might join a site to look at pictures of her nephew and five years later believe in a flat earth.

what began as the most elastic and snappable verbal play soon emerged in jargon, and then in doctrine, and then in dogma.

A picture of a new species of tree frog that had recently been discovered. Scientists speculated that the reason it had never before been seen was because, quote, “It is covered with warts and it wants to be left alone.” me me unbelievably me it me

When folk music became popular again, it reminded people that they had ancestors, and then, after a considerable delay, that their ancestors had done bad things.

It should not be true that, walking the wet streets of international cities, she should suddenly detect the warm, the unmistakable, the broken-to-release-the-vast-steam-of-human-souls, the smell of Subway bread. That she should know it so instantly, that she should stop in her tracks, that she and her husband should turn to each other joyously and sing in harmony the words EAT FRESH. No, it should not be true that modern life made us each a franchise owner of a Subway location of the mind.

“Your attention is holy,” she told the class, as her phone buzzed uncontrollably in her back pocket, for a long-ago joke she had made about a Florida politician “who nearly died during elective taint-lengthening surgery” was receiving renewed attention that morning.

In contrast with her generation, which had spent most of its time online learning to code so that it could add crude butterfly animations to the backgrounds of its weblogs, the generation immediately following had spent most of its time online making incredibly bigoted jokes in order to laugh at the idiots who were stupid enough to think they meant it. Except after a while they did mean it, and then somehow at the end of it they were Nazis. Was this always how it happened?

“Don’t normalize it!!!!!” we shouted at each other. But all we were normalizing was the use of the word normalize, which sounded like the action of a ray gun wielded by a guy named Norm to make everyone around him Norm as well.

Context collapse! That sounded pretty bad, didn’t it? And also like the thing that was happening to the honeybees?

Each day to turn to a single eye that scanned a single piece of writing. The hot reading did not just pour from her but flowed all around her; her concreteness almost impeded it, as if she were a mote in the communal sight. Sometimes the pieces addressed the highest topics: war, poverty, epidemics. Other times they were about going to a deli with a poor friend who was intimidated by the fancy ham. And we always called it that: a piece, a piece, a piece.

A conversation with a future grandchild. She lifts her eyes, as blue as willow ware. The tips of her braids twitch with innocence. “So you were all calling each other bitch, and that was funny, and then you were all calling each other binch, and that was even funnier?” How could you explain it? Which words, and in which order, could you possibly utter that would make her understand? “. . . yes binch”

Even a spate of sternly worded articles called “Guess What: Tech Has an Ethics Problem” was not making tech have less of an ethics problem. Oh man. If that wasn’t doing it, what would??

I have eaten the blank that were in the blank and which you were probably saving for blank Forgive me they were blank so blank and so blank

Why did rich people believe they worked harder? Her theory was that it was because they identified with the pile of money itself. And gathering interest, multiplying hotly, climbing its own slopes like a fever, heightening its silver, its gold, its green—what was that but work? When you thought about it that way, they never slept, but stayed wide-eyed as numerals 365 days a year, every last digit of them busy, awake in the clinking, the shuffle, the rustle, while eagles with pure platinum feathers swooped above them to create a wind. When you thought about it that way, of course they deserved it all, and looked with rightful contempt at the coppery disgraces all around them: those two cents that refused to even rub themselves together.

The words Merry Christmas were now hurled like a challenge. They no longer meant newborn kings, or the dangling silver notes of a sleigh ride, or high childish hopes for snow. They meant “Do you accept Herr Santa as the all-powerful leader of the new white ethnostate?”

When she was a child, the thing she feared most—besides pooping little eggs—was having the hiccups for fifty-five years, like the cursed man she had read about in her water-damaged Guinness Book. But when she came of age she realized that everything about life was having the hiccups for fifty-five years.

The more closely we could associate a diet with cavemen, the more we loved it. Cavemen were not famous for living a long time, but they were famous for being exactly what the fuck they were supposed to be, something we could no longer say about ourselves. A caveman knew what he was; the adjective was a sheltering stone curve over his head. A man alone under the sky had no idea.

The people who lived in the portal were often compared to those legendary experiment rats who kept hitting a button over and over to get a pellet. But at least the rats were getting a pellet, or the hope of a pellet, or the memory of a pellet. When we hit the button, all we were getting was to be more of a rat.

how strange, she had thought, biting into a slice of bread-and-butter that tasted like sunshine in green fields, to live in a country where someone can say “the massacre” and you don’t have to ask which one.

What do you mean you’ve been spying on me? she thought—hot, blind, unreasoning, on the toilet. What do you mean you’ve been spying on me, with this thing in my hand that is an eye?

When she set the portal down, the Thread tugged her back toward it. She could not help following it. This might be the one that connected everything, that would knit her to an indestructible coherence.

That the shorthand we developed to describe something could slowly, brightly, wiggle into an example of what it described: brain worms, until the whole phenomenon contracted to a single gray inch. Galaxy brain, until something starry exploded.

He believed the modern world had no respect for its elders, and consequently had forgotten about God, the oldest man alive.

The cursor blinked where her mind was. She put one true word after another and put the words in the portal. All at once they were not true, not as true as she could have made them. Where was the fiction? Distance, arrangement, emphasis, proportion? Did they only become untrue when they entered someone else’s life and butted, trivial, up against its bigness?

“Did you read . . . ?” they said to each other again and again. “Did you read?” They kept raising their hands excitedly to high-five, for they had discovered something even better than being soulmates: that they were exactly, and happily, and hopelessly, the same amount of online.

Gap. Gap. Gap. Gap. Great gap in the thrumming of the knowing of the news.

She had not realized what a close call she had had till recently, for now in the portal, men were coming up through the manholes to confess how near they had come to being radicalized, how they too had wandered the sewers of communal thought for days at a time, dry-mouthed and damp under the arms. How they were exposed to the mutagenic glowing sludge just long enough to become perfectly, perfectly funny, just long enough to grow that all-discerning third eye.

“Any kids?” one of the nurses asked her. No. She hesitated so long she could feel her hair growing. A cat. Named Dr. Butthole.

During those weeks animals came up to her on the street and pushed their soft muzzles into her palm, and she always said the same two words, never wondering whether they were a lie or not, the words that dumb things depend on us to say—because when a dog runs to you and nudges against your hand for love and you say automatically, I know, I know, what else are you talking about except the world?

“Still,” the doctors urged them finally, “don’t go home and look this up.” That was the difference between the old generation and the new, though. She would rather die than not look something up. She would actually rather die.

All day she drank in information, but no one was telling them the main thing. No one was telling them how long they would have her, how long the open cloud of her would last.

“I guess I’ll go home when the handle of vodka runs out,” she told herself, like the opposite of Cinderella, though still slipping into the glass that fit her perfectly.

Big thanks to Jason Kottke for introducing me to this book (and also for this method of recommending books to others)