Looking back to 2003, here is an essay I completed in graduate school. Posting here in part for posterity, but also to reflect on how I once saw the world and design. How might we look back, to bring clarity in how we see going forward?

I attended graduate school for architecture from 2003-2005, right at the peak of the transition towards the digital. It was a special time in our field’s collective history, and one that I am grateful to have participated in while in school. Seeing design and design methods shift so dramatically away from the analogue was critical for me, especially since I had the advantage of being educated on both sides of this history of architecture. Learning design and making by hand as well as through advanced computation, fabrication, tools and methods, has allowed me to discover new pathways within the design world.

Frederick Kiesler

I attended graduate school for architecture from 2003-2005, right at the peak of the transition towards the digital. It was a special time in our field’s collective history, and one that I am grateful to have participated in while in school. Seeing design and design methods shift so dramatically away from the analogue was critical for me, especially since I had the advantage of being educated on both sides of this history of architecture. Learning design and making by hand as well as through advanced computation, fabrication, tools and methods, has allowed me to discover new pathways within the design world.

Frederick Kiesler

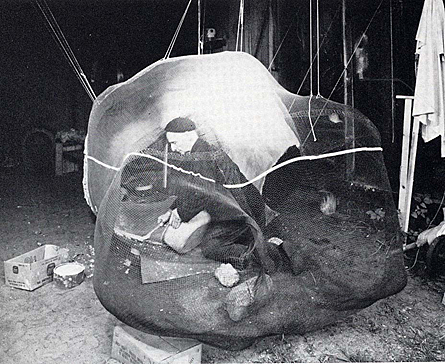

Inside the Endless House…

“What are you my colleague architects and engineers doing? How do you use your superpower given to you by the universe? Why do you remain routine draftsmen, cocktail sippers, coffee gulpers and making routine love? Wake up, there’s a new world to be created within our world.”1

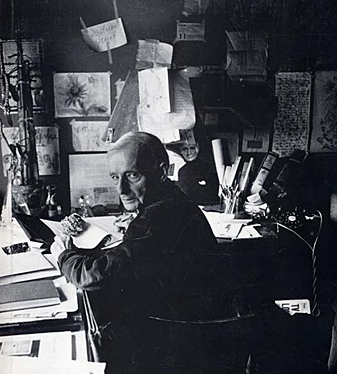

Frederick Kiesler – 1960 – In Bedroom/study at home

Frederick Kiesler’s call to all architects and designers to challenge the forces of the “routine” was a principle that Kiesler spent a lifetime crafting. A conviction that he would continuously articulate through commissioned and noncommissioned architectural projects, sculptures, paintings, poetry and countless manifestoes. A lifetime that was spent researching, developing, and building one core concept. A concept that was not in line with the current International Style modernist whose formal language and ideas were interested in extensive infinite gridded space. For Kiesler rather, it was a pursuit of intensive and endless space based on continuous curvilinear vectors.2

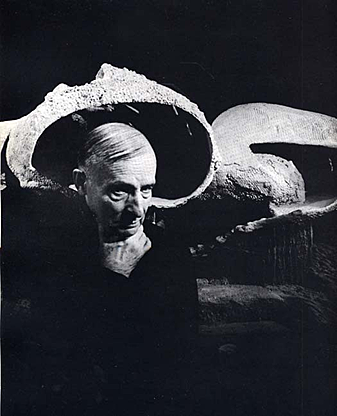

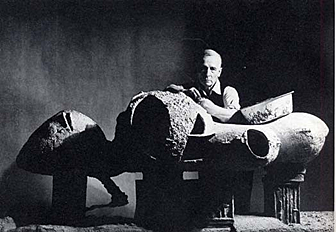

Frederick Kiesler – 1959 – In front of the Endless House

Since Kiesler’s death in 1965, his notion of Endless Space and his studies of the Endless House in particular, have resurfaced in recent architectural discourse. New technologies have emerged that are now provoking different questions regarding the tectonics and material potentials within the concept of The Endless House.

What did Kiesler really mean by Endless Space? How did Kiesler intend for The Endless House to change the face of architecture?

What did Kiesler really mean by Endless Space? How did Kiesler intend for The Endless House to change the face of architecture?

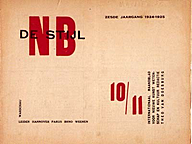

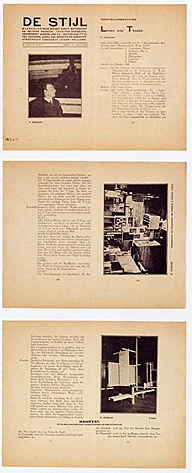

Frederick J. Kiesler was born on September 22nd in Cernauti, Romania, the son of Dr. Julius and Maria Kiesler. He studied art and design at the Academy of Visual Arts in Vienna in 1910 but left without a diploma in 1913. By the early nineteen twenties, he was already well known as a stage designer throughout Europe and instigated such innovations as film- projected backdrops and the theater-in- the-round. In 1923, he was invited to join the Dutch De Stijl and in 1925, Josef Hoffmann invited him to design the Austrian theater section of the Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris. Kiesler described his installation in a manifesto (“Manifesto of Tensionionism”, April 1925) as a design for the future mega city (titled “City in Space”)3 and published other essays in the journals G and De Stijl.

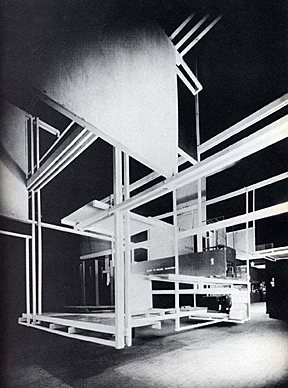

In his manifesto, Kiesler declared “No More Walls”4 as he described the floating framework and intersecting planes of City in Space. Kiesler’s idea of a utopian city was the pinnacle of his European career, while expressing his attraction to themes of the architectural avant-garde. City in Space was applauded as one of the boldest creations of the De Stijl tradition5 but was also the beginning of his eventual departure from this very tradition. His declaration of “No More Walls” would in actuality be foreshadowing for a concept far more potent than his City in Space exhibition.

In his manifesto, Kiesler declared “No More Walls”4 as he described the floating framework and intersecting planes of City in Space. Kiesler’s idea of a utopian city was the pinnacle of his European career, while expressing his attraction to themes of the architectural avant-garde. City in Space was applauded as one of the boldest creations of the De Stijl tradition5 but was also the beginning of his eventual departure from this very tradition. His declaration of “No More Walls” would in actuality be foreshadowing for a concept far more potent than his City in Space exhibition.

City in Space – 1925 - Paris

In 1926 Kiesler and his wife (Stefanie Frischer) arrived in New York to install a section of the International Theater Exhibition for Jane Heap at the Steinway Building. Upon Kiesler’s arrival, he published an essay titled “The Theater is Dead” and lectured on his concept for an Endless Theater based on a large spheroid model of a four-dimensional theater without a stage. Echoing back to his earlier declarations, Kiesler’s investigations into a multi-dimensional, stage-less theater are in fact the beginnings of what would become a radically new concept of form and content appropriately called “Endless Space”.

Like Walt Whitman before him, who spent a lifetime redrafting and perfecting his only “book” (Leaves of Grass); Kiesler embarks on a concept that he will devote the last 35 plus years of his life pursuing. Unlike Whitman however, Kiesler would never see an actualization of his tireless and often obsessive efforts beyond drawings and models, photographs, and his writings (manifestoes, essays and poetry alike).

Kiesler arrives in New York City - 1926

The foundations of which the greater concepts of Endless Space were shaped are in a theory formulated by Kiesler in the 1930’s entitled the “Correalist Theory.”6 Kiesler believes that the essence of reality is not in the “thing” itself, but in the way it correlates and orders itself to its environment. Kiesler deemed that it was essential to disregard the boundaries that separate the different arts. These boundaries need to be dissolved and Kiesler even proclaimed that “painters, sculptors, and designers, driven away by functionalism, will return from exile to be welcomed by architecture.”7

Kiesler believes that it is in fact the static nature of the “box” and the machine driven ideal of then current modernist architecture (specifically Le Corbusier) that forces a single guided functionalism on man that is not his desired environment. In an effort to distance himself from these obstacles to the body, Kiesler proclaims “Functionalism is determination and therefore stillborn. Functionalism is the standardization of routine activity. Functionalism relives the architect of responsibility to his concept.”8

It is through painting, sculpture, poetry and architecture that man can create an environment that is more fitting to his agenda, his nature and not one that fits into a box that is predetermined by the functions pushed upon man by others. Instead Kiesler envisions a concept that “embraces man and his environment as a globalizing system consisting of complex reciprocal relationships”9 that separate artistic genres.

Kiesler’s early developments of his correalist theory find their greatest fulfillment not in urbanistic concepts (a departure from City in Space) but, rather, in a simple single-family house. Kiesler sees the single-family house as the smallest unit of human coexistence and is therefore the most important. His notion of Endless Space as a catalyst for correalism begins to come into focus with the Space House project in 1933.

Space House – 1933 – New York

Space House – 1933 – New York

Space House – 1933 – New York

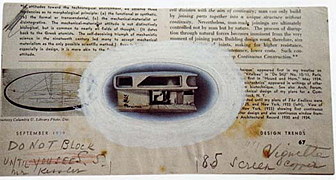

Cut out from Architectural Record – 1939

The Modernage Furniture Company in New York commissioned Kiesler to build a full scale “model” prototype of a single family house for the window displays of the furniture company. With the aid of new materials and techniques (pre- stressed concrete, plastic and glass) Kiesler aspires to create a unitary, monumental space without foundations in which the surfaces that typically act as boundaries (floors, walls, ceilings) would form a transition and continuum that reflects the demand for maximum flexibility in the layout of the interior space.10 Kiesler’s “system of tension” in City in Space and the three dimensional possibilities of his earlier space theater project were fundamental principles to the development of the Space House and opening up the potential for interior space within the context of a house.

The Space House becomes the first major departure from the formal principals of functionalism based on the rectangle of the international style and Kiesler’s first real articulation of his early developing theories of correalism and theoretical notions for the single-family house. This refines Kiesler’s focus from a concept of Endless Space to the pursuit of the Endless House.

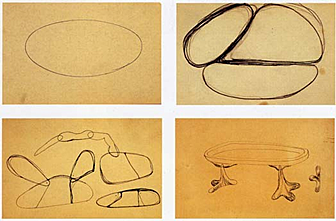

Studies for cast aluminum table - 1935

Two part nesting table – 1935-38

In 1934, Kiesler became the director of scenic design at The Julliard School of Music and in 1935/36; Kiesler designs his famous Biomorphic Aluminum Nesting Table. A table that expresses some of Kiesler’s architectural ideas at a new scale; a scale shift that enriches Kiesler’s ideas on the correlations of our environment (big and small) and its relationship to the body.

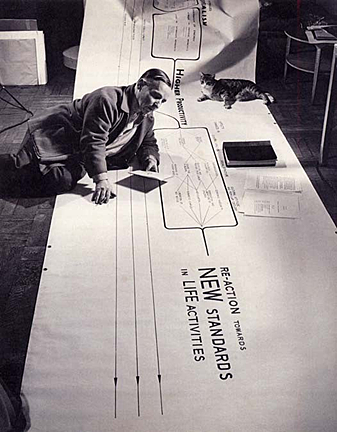

In 1937, Kiesler begins to publish a series of articles in Architectural Record discussing his investigations on the idea of “design correlation.” However, it wasn’t until 1947 that Kiesler drafted his Manifesto on Correalism. This manifesto wasn’t published until 1949 but it is within this text that we really begin to understand Kiesler’s ideas and developments on correalism, the Endless House, architecture, art and life in general. Kiesler sets out to put down on paper the historical evolution of the Endless House which he sees as a work already 20 years in progress; but also to unify architecture and the arts.11

Kiesler with “Correlation Chart” – 1937 – New York

Kiesler begins his manifesto by aligning himself with the reader “We are living on the edge. We-you-me!”12 and setting himself against “high-art”, “so-called teachers” and the “false temples, for architecture and the people’s art have died.”13 Kiesler makes a call to look back into ourselves “and become cave dwellers.” To support the “boundless edifice”14 and search for a dwelling of “simpler construction and richer inspiration.”15

Kiesler continues his assault on modernism’s infliction on the milieu and proclaims that “We have become slaves to an industry lost in a mechanical world. The house is neither a machine nor a work of art. The house is a living organism, not just an arrangement of dead material: it lives as a whole and in the details. The house is the skin of the human body.”16 This is an important statement for Kiesler who is striving to define his ideas on space in stark contrast to what he feels is closing in all around him. A battle against the imitated “box” and Le Corbusier’s idea of a house as a machine for living. Kiesler does not see the house as a machine that the body has to tolerate as a complex organization of foreign parts. Rather, Kiesler defines the house as the skin for the body. An organism that should be fluid, move and adjust to the body and its movements.

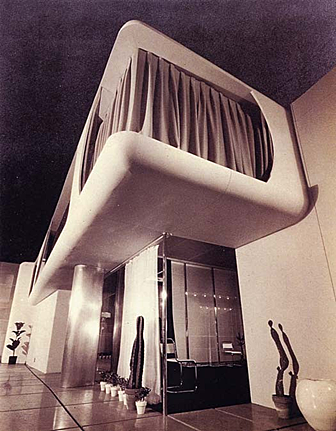

Kiesler’s ideas on the (re)positioning of the human body and architecture is I believe, most evident in his 1942 design and construction of the gallery Art of This Century for Peggy Guggenheim. It is here that Kiesler begins to question the way art is displayed and the positions in which the human body negotiates and situates itself in a gallery. The space he creates can change how the body understands art and becomes a locust for change in architecture and its context. Kiesler’s belief in the importance of the gallery visitor’s active role in experiencing art begins to shape his notions into actual physical elements to be engaged. Kiesler stated that when man comes into contact with a work of art, he must “recognize his act of seeing – of ‘receiving’ as a participation in the creative process that is no less essential than the artist’s own.”17

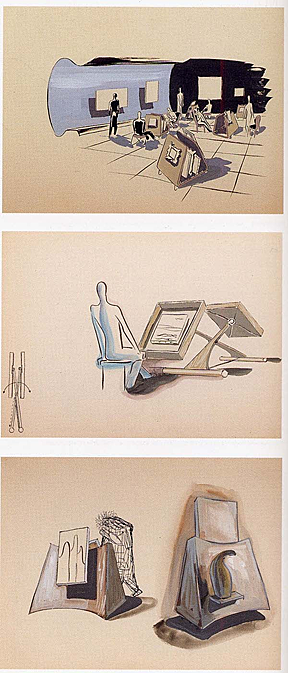

Studies for Art of This Century - 1942

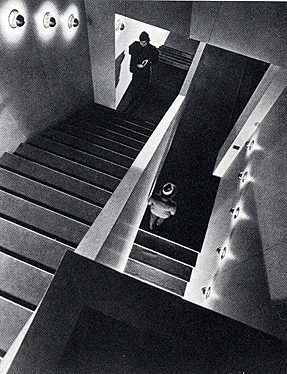

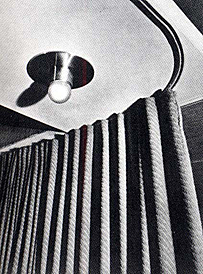

Kiesler’s ideas are successfully employed in this project for three main reasons. First, he manipulated the “real” space and created a sculptural environment. Secondly, he took the typically passive role of the viewer and made them an active participant as they moved through space. Finally, he transformed the art from just objects in space to real things in real space.18 Kiesler, searching for the correlation between space, spectator, and art “object” tried to dissolve all of the barriers that a traditional gallery design imposes on the body. He constructed all of the displays to be adjustable individually in their heights and angles to the observer’s desires. The displays were also mobile and easily dismountable so they could be quickly and effortlessly rearranged. He removed all of the frames because “the framed painting on the wall has become a decorative cipher without life and meaning…“19 Kiesler believed the frames actually cut off the work of art from the space of life. “The frame was suppressed, and the painting liberated. The removed frame was replaced by another. That is: the general architecture of the room. Painting became a part of the architectural whole and was no longer artificially isolated.”20 The rigid walls of the gallery were bent and curved to flow into the floor and the ceiling.

Art of This Century – 1942 – New York

Changing light patterns and sound effects would illuminate and accentuate different pieces of work so the gallery would “pulsate like your blood. Ordinary museum lighting makes painting dead.”21 Kiesler goes beyond the optical attempts of El Lissitzky’s galleries before him by engaging the observers many senses from optics, audible and physical interaction. These ideas attempt to bring equal harmony to all of the arts within the gallery space and was applauded and well received.

The 1942 gallery Art of This Century for Peggy Guggenheim project, brought forth some of the greatest developments and studies for the interior of the Endless House, by negotiating his ideas and sensitivities to the body in the interior space as translated through his ideas of correalism. Although the basic concepts of the Endless House began arguably in 1924, it isn’t until 1950 that we see a flurry of sketches and models publicly giving an outward appearance to the Endless House.

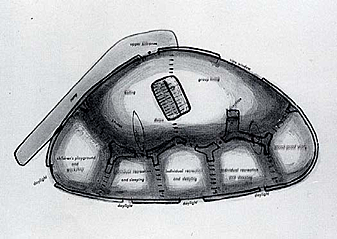

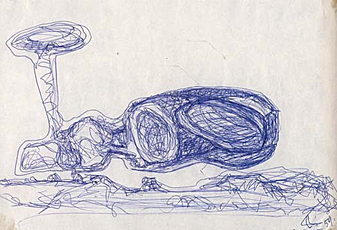

The initial studies show a flattened spheroid similar to his Space Theater studies from 1925. Kiesler’s first sketches are rather rough and initially a dry translation of his Manifesto of Correalism that was published one year prior. He argues that the spheroid shape is actually based on a lighting system. A shape that would allow light to reach the “shadowy corner of his cave” and not get broken up by the corners and interior walls of a conventional building volume. Rather, it is a shape that promotes the “social dynamics of two or three generations living under one roof… preferable for group living demand double or even triple heights in some areas.”22

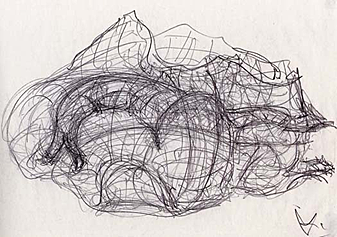

Although Kiesler is inferring sectional relationships, his plan sketch is actually quite predictable and banal. One criticism of Kiesler is the discordance between the potential his models suggest and the static “architectural” drawings (plans, sections, etc.) that are unfortunately associated with them. When Kiesler is freehand sketching his interior visions, we recapture the spirit he touted in his manifesto, but as soon as he tries to quantify and make “rigid” his un-rigid lines and surfaces, he loses the qualities of space continuum, the ‘system of tension’ he is after.

The initial studies show a flattened spheroid similar to his Space Theater studies from 1925. Kiesler’s first sketches are rather rough and initially a dry translation of his Manifesto of Correalism that was published one year prior. He argues that the spheroid shape is actually based on a lighting system. A shape that would allow light to reach the “shadowy corner of his cave” and not get broken up by the corners and interior walls of a conventional building volume. Rather, it is a shape that promotes the “social dynamics of two or three generations living under one roof… preferable for group living demand double or even triple heights in some areas.”22

Although Kiesler is inferring sectional relationships, his plan sketch is actually quite predictable and banal. One criticism of Kiesler is the discordance between the potential his models suggest and the static “architectural” drawings (plans, sections, etc.) that are unfortunately associated with them. When Kiesler is freehand sketching his interior visions, we recapture the spirit he touted in his manifesto, but as soon as he tries to quantify and make “rigid” his un-rigid lines and surfaces, he loses the qualities of space continuum, the ‘system of tension’ he is after.

Section study for Endless House - 1950

Model of Endless House - 1950

Endless House study - 1959

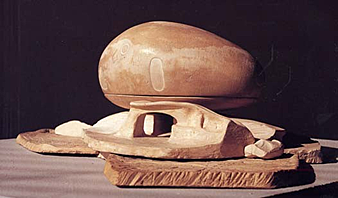

In 1952, along with Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome, Kiesler introduces his Endless house in an exhibition title Two Houses: New Ways to Build at the Museum of Modern Art. After the exhibition, The MOMA commissioned Kiesler to design a full-scale prototype of the Endless House for the museum garden where it would remain for two years. This gave Kiesler the opportunity to build large- and small-scale models of the Endless House in which he hoped to finally tackle some of the detail and tectonics issues that he was questioning from his earlier studies. Unfortunately, the project never came to completion and only his study models, drawings and photographs were presented as a part of the Visionary Architecture exhibit in September 1960.

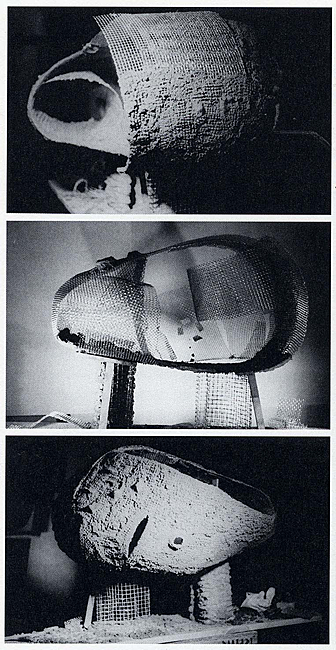

Kiesler’s studio with Endless House model in progress - 1959

His models do however show us an idea that has come a long way from his drawings in 1950. We now see a rich series of spaces, folding and unfolding with internal stairs, private spaces, sectional relationships and interior and exterior walls that emerge seamlessly with the same continuous surface tension with all the surfaces working together. In conjunction with his text based investigations, we understand his intensions for the exterior of the Endless House were to be one of reinforced concrete on a wire mesh substrate. The windows were to be irregular shaped apertures that would be covered with a semi-transparent molded plastic. Bathing pools would be scattered throughout, replacing conventional bathtubs. The flooring was to have a variety of textures. At times pebbles, sand, rivulets of water, grass, planks and heated terra-cotta tiles would continuously stimulate the occupant through touch. The interior walls would be colored with frescoes and sculptures.23

Endless House study - 1959

Endless House model in progress – 1959

Till the end, Kiesler considered the Endless House a total work of art. In theory, the sense of Kiesler’s correlated space to the human body in both form and function cannot be denied but we are only left with suggestions of how the materials might have been treated.

Despite these limitations, Kiesler’s studies did accomplish numerous other notable advancements in architecture. Kiesler did set out to challenge the machined “box” that architecture was trapped in and did put forth a series of studies that seriously questioned the rigid boxes and how the human body interacts with it. Kiesler’s gallery spaces opened up new questions of corners, thresholds between floors and walls and how the body engages them. Once he tore the frames off the paintings, something profound did happen. Kiesler revealed the frame as a trap, a static container with points of negotiated corners along its trajectory that always cut the non-rigid body off from it.

Kiesler dissolved the rigid hierarchy of the privileged corners and created a continuous surface that has no beginning and no end. An organic surface that he argues fits more comfortable as the environment for the urgent and eternal need of the human body. Kiesler said that “the ‘Endless House’ is called ‘Endless’ because all ends meet, and meet continuously.”24 An idea, Kiesler argues, that a surface with no beginning and no end is more appropriate for a house because it assimilates with the human body (which Kiesler argues also has no beginning and no end). With this argument, Kiesler reasserted the human body’s importance into an architectural climate that had long been ignoring this.

Unfortunately, because he was unable to build a full-size version of the Endless House, numerous opportunities of unforeseeable negotiations of materiality and surface transitions were under developed. With the inability to draw and model some of the discreet moments of transition (no longer floor to ceiling but between sand and terra-cotta for example) the general tectonic strategies are unknown. However, despite leaving us wanting more, Kiesler’s studies have taken architecture down a remarkable path of desire and rediscovery of the interface potentials of the human body and architecture.

With the emergence of advanced computation, modeling and simulation of today, we are seeing more and more the opportunities to explore vector based curved surfaces with greater refinement than that of Kiesler’s plaster models.

Endless House presentation drawings at MOMA – 1959 – New York

Kiesler’s ideas and philosophies challenged the architecture of the 20 century and continue to push the current circles of the avant-garde towards the explorations of a non-linear architecture. From the obvious formal and more intriguing conceptual parallels, Kiesler’s impact on current architectural discourse is undeniable. With the core concepts of the Endless House resurfacing and his Manifesto of Correalism still profoundly relevant, Kiesler’s research is still as rich and tantalizing as it was forty years ago.

Advancements in material technologies have allowed us to do with concrete or steel, plastic or glass things that Kiesler could have only dreamed about. Digital media has allowed for photo-realistic renderings and more accurate study of light and material behavior within architectural paradigms. In conjunction with emerging technologies, we have really only scraped the surface of what Kiesler was truly after in his Endless House studies. By virtue of pushing architectural theory to its limits, by challenging the everyday realities, Kiesler’s vision of a form that does not follow function but rather a function that follows a vision25 may one day be achieved in meaningful ways, not just formal gimmicks.

For it is Kiesler who “convinces us that endlessness and continuity are more than unattainable ideals, but concepts that may lead us to a transformation of what is merely given as reality.”26 In accordance with Kiesler, if we continue to challenge what is given as reality, we will place ourselves that much closer to the potential for what architecture is capable of doing… a potential that is indeed Endless.

For it is Kiesler who “convinces us that endlessness and continuity are more than unattainable ideals, but concepts that may lead us to a transformation of what is merely given as reality.”26 In accordance with Kiesler, if we continue to challenge what is given as reality, we will place ourselves that much closer to the potential for what architecture is capable of doing… a potential that is indeed Endless.

Endless House model - 1959

------------

Work Cited

1 Kiesler, Frederick., et al. “Continuity, the new principal of Architecture.” Endless Space. Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2001 pg. 54

2 Lynn, Greg., et al. “Rethinking Kiesler – Endless Space Symposium” Endless Space. Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2001 pg. 81

3 Bogner, Dieter., et al. Frederick Kiesler – Whitney Museum.

The Whitney Museum of American Art, 1989 pg.48

4 Kiesler, Frederick, “Vitalbau-Raumstadt-Funktionelle Architektur,” De Stijl 6/10-11 (1925): 141 ff

5 Barr jr, Alfred H., Cubism and Abstract Art, Exhibition catalogue. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1936

pg. 144

6 Kiesler, Frederick, “On Correalism and Biotechnique,”

Architectural Record 86/3 (September 1939): 60-75

7 Kiesler, Frederick, “Manifeste du Correalisme,” L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui (June 1949)

7 Kiesler, Frederick, “Manifeste du Correalisme,” L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui (June 1949)

8 Kiesler, Frederick, “Manifeste du Correalisme,”

L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui (June 1949)

9 Bogner, Dieter., et al. Endless Space. Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2001 pg. 11

10 Bogner, Dieter., et al. Endless Space. Hatje Cantz

Publishers, 2001 pg. 16

11 Bogner, Dieter., et al. Endless Space. Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2001 pg. 14

12 Kiesler, Frederick, “Manifeste du Correalisme,”

L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui (June 1949)

13 Kiesler, Frederick, “Manifeste du Correalisme,”

L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui (June 1949)

14 Kiesler, Frederick, “Manifeste du Correalisme,”

L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui (June 1949)

15 Kiesler, Frederick, “Manifeste du Correalisme,”

L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui (June 1949)

16 Kiesler, Frederick, “Manifeste du Correalisme,”

L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui (June 1949)

17 Goodman, Cynthia., “Frederick Kiesler: Designs for Peggy

Guggenheim’s Art of This Centry Gallery,” Arts Magazine, 51 June 1977, pg.92

18 Phillips, Lisa., et al. Endless Space. Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2001 pg. 28

19 Kiesler, Frederick, “Press Release Relating to the

Architectural Aspects of the Gallery,” Art of This Centry Gallery, 1942, typescript, Kiesler Estate Archives, pg. 1 20 Kiesler, Frederick, “Manifeste du Correalisme,” L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui (June 1949)

21 Quoted in Newsweek, October 2, 1942

22 Kiesler, Frederick., “Frederick Kiesler’s Endless House and its Psychological Lighting”, in:Interiors, November 1950, pg. 123-125

23 Phillips, Lisa., et al. Frederick Kiesler – Whitney Museum. The Whitney Museum of American Art, 1989 pg.125-127

24 Kiesler, Frederick, Inside the Endless House . New York: Simon & Schuster, 1966 pg. 566

25 Kiesler, Frederick, “Manifeste du Correalisme,”

L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui (June 1949)

26 Woods, Lebbeus., et al. “Frederick J. Kiesler Out of Time” Endless Space. Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2001 pg. 66

All images in article are Copyright: Austrian Frederick and Lillian Kiesler Private Foundation Source: Archive of the Kiesler Foundation Vienna

The photographer: Art of This C.: Berenice Abbott, commerce graphics Ltd.

Kiesler in front of Endless House model: Hans Namuth