Evolving Design Thinking in Your Organization 08-2018

No children will die, no fires will burn

Some customers will buy, some customers will churn

All leaders come, all leaders go

Conflict is between thinking fast and slow

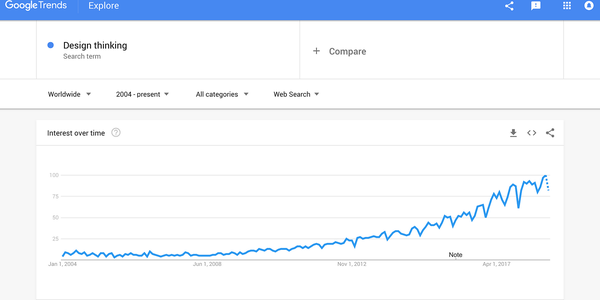

Design thinking is peaking in its popularity and needs to evolve to remain useful.

“Ok Google, confirm my bias.”

Design thinking has been on the rise for the past couple of decades. Some argue that its spread is similar to that of STDs or the proliferation of BS while others have been a bit fairer, chalking it up to a failed experiment. According to T. Swift, the haters gonna play and the players gonna hate. Or something like that… So regardless of where you fall in this divisive matter, I’m here to argue that the debate of whether design thinking’s mere existence is a good thing or a bad one is behind us. It is here and as more and more companies adopt design thinking it is time to evolve our conversation from whether it is good or bad towards what about it is useful and what about it needs to change.

Doktor Murners Narrenbeschwerung (1512) das Kind mit dem Bade ausschütten Ex Bibliotheca Gymnasii Altonani ala Stickies

Noting the shared criticism that design thinking is poorly defined, let us add some definition to it before going further. Beyond being an human-centered process mimicking the scientific method in spirit, if not in rigor, design thinking is really about how organizations make intentional choices to benefit their customers/beneficiaries— and, hopefully, their employees, communities, and environment as well. These choices can and do cover a wide-spectrum and is cause for the necessary confusion that comes from defining the differences between interconnected disciplines. From user interface to user experience design, design strategy + business design, organizational design, and increasingly ownership design, thanks to the resurfacing interest in cooperatives and non-venture funded organizations (think En Spiral). Call it a mindset, a process, a toolkit of methods to be applied at different stages of a project by different members of a team or organization, design thinking is ripe for misunderstanding and therefore, misuse.

As a known user and occasional abuser of design thinking, myself, I’ve come to realize the need for other professionals and organizations to add dimensionality to their application of the ever-alluring, but ambiguous nature of design thinking. Especially with the rising ubiquity of design thinking workshops and classes online/offline set with the backdrop of international firms and companies rapidly acquiring any design or creative agency they can get their hands on–if you can’t beat ‘em, buy ’em (see Jon Maeda’s 2018 Design in Tech Report).

What follows are several dimensions in which to assess your personal and/or organization’s use of design thinking. Regardless of where you fall on either, these categorizations are less about good vs bad and more about how useful/appropriate your current approach may be for the choices you are making and the outcomes you’re trying to achieve.

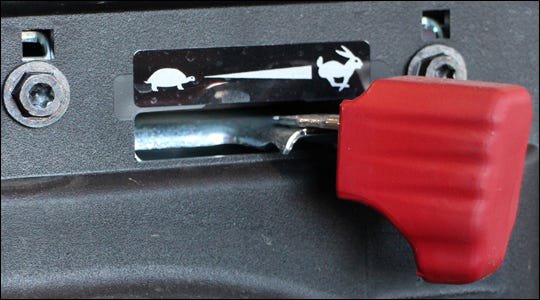

Fast and Slow (Speed of Delivery)

How rushed is the design thinking process at your organization? Is a half-day brainstorming session expected to generate perfectly executable ideas for the following year? Conversely, does decision making at your organization drag on and on getting ever more abstract and disconnected from the very people you’re looking to serve? Design thinking fast and slow is about finding the right tempo or cadence for applying the process in your organization. Think about music; some songs sound great at faster tempos, while some truly shine when slowed way down (hear it for yourself: Justin Bieber slowed 800%)

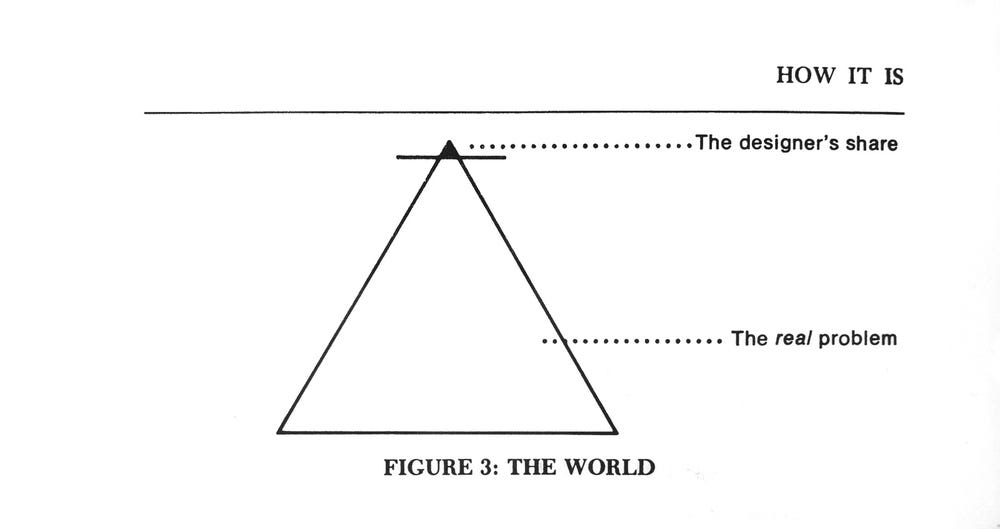

Today the design thinking process seems to only be accelerating while the issues it attempts to tackle are growing in scale and complexity. Design marathons have turned into Design sprints, design charrettes have been condensed into design blitzes, and now, even 5 day design sprints have been shortened by a day to use less time and require less team input. Meanwhile, design thinking is necessarily turning its attention from consumer products to designing for the real world and all the wicked problems that come with it, as designers are working their way down Papanek’s pyramid.

From Designing for the Real World by Victor Papanek (1971)

This leaves many of us mashing together tools and methodologies from the design thinking suite to address problems of all shapes and sizes in a variety of (multi-)organizational settings replete with their own constraints. A Google-esque design sprint is a great fit for dedicating time, a team, and resources towards incrementally developing and testing well-selected parts of a product. However, it may leave your team wanting for more if you are trying to create entirely new processes for reducing financial inequality in the USA and beyond (a notably poor issue to address in a time-boxed silo).

Part of design thinking’s appeal is it’s bias towards action, which encourages testing out potential solutions versus trying desperately to discover the perfect solution to a problem through analysis alone. In this sense, the faster we move on a project, the faster we might reach a better solution or at least progress. Of course, when speed is used for efficiency’s sake alone, we often risk a project’s effectiveness. Yes, it is more efficient to include fewer team members, especially more senior level members with their busy schedules and whatnot. However, this logic quickly gets away from itself, begging questions such as, “Why take more time inviting the intended users/beneficiaries of any product or service to participate in the process when we can just run a quick, remote user interview? Or better yet send out a mass survey?”. Yet, sometimes, if we slow down to allow input from multiple stakeholders and allow ourselves to reflect on the issues we’re addressing, the final designs will ultimately be more effective.

Design thinking fast and slow is thus a tradeoff we must always make based on the constraints of a project–namely time. Go too fast and you risk leaving out valuable input from project stakeholders and creating fixes that don’t fix their intended problem, undoing any gains in efficiency anyways. #EfficientIneffectiveness. #MoveFastAndDestroyTheWorld. Go too slow and experience paralysis by analysis, not even seeing the end of the project and leaving your users/beneficiaries no better off then when you started. Therefore it is important at your organization to reconsider what you mean by “efficiency” when the issue of shortening a workshop or session comes up. Does that mean involving fewer stakeholders, skipping steps of the process, or neglecting the need of reflection for more nuanced challenges? And when it comes to project“effectiveness”, it is important to consider the possibility of diminishing returns. When have we done enough research to make an informed design decision? How much more effort do we really need to put into developing our minimum viable product before we can test it with real people and gain real insights?

So much of the current language around design thinking leans towards quickening speeds that we need to remind ourselves the value of pumping the brakes every once in a while. “Rapid prototyping” is great early on in the development of a new/improved product or service, but clearly the goal is to go beyond that stage and engage in the craft of refining whatever the product or service is for the sake everyone involved. Similarly, the notion of “rapid ethnography” has been tremendously helpful in warming organization’s up to the importance of actually talking to and involving the very people they are designing for, but at times runs quite counter to the practice and intent of ethnography to truly understand culture and behaviors with out a hidden agenda. True understanding takes time and moving fast seems to be more associated with breaking things these days (e.g. personal privacy, democracy, etc.) rather than fixing them.

So consider where design thinking might be helpful in your organization to speed up unnecessary dithering, back and forth decision making. Also think about where you might be going too fast and skipping over voices, details, and aspects of your products and services that really matter. Ideally, you’ll want to find the right tempo that fits your time constraints, adequately addresses the problem at hand, and involves the many related stakeholders within and outside of your organization. And if that sounds like a tall order, worry not. Design thinking is all about iteration. So if you have to move a project along in short bursts, go for it, just make sure to scope the pieces of the project realistically to what can be accomplished and rinse and repeat as needed. Design thinking is all about iteration :) ;] :D.