Prologue:

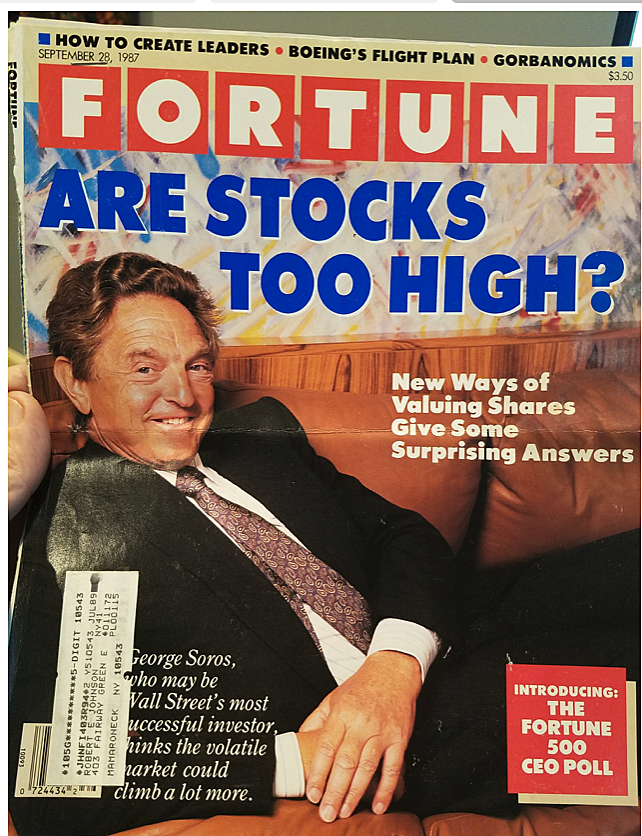

1. The article from which the following is excerpted, was originally published in Fortune magazine on September 28, 1987. You can read the whole thing here: ARE STOCKS TOO HIGH?.

2. Black Monday (1987) - Wikipedia, talks about market volatility in the week starting on October 19, 1987. The above wiki link may be treated as a kind of a 'disclosure'; it wouldn't be fair to readers if I had not linked to it.

3. I do not wish to draw any parallels whatsoever, because I don't think that history repeats exactly. In other words, I don't expect things to repeat, and that is strictly my opinion; I want to make that very clear. Readers shouldn’t extrapolate on the basis of the above links.

Almost every market participant ‘expects’ a correction. Why is that? The most common answer is: ‘because stocks are too high’. The blurb on the cover of the magazine shown above says: ‘New Ways of Valuing Shares give some Surprising Answers’. Hence, I found the fortune article extremely relevant. I have copied and pasted excerpts of the original article. I haven't commented at all on any of the things that I have excerpted; reason being, it doesn't warrant any commentary.

However, I have added tittles to the excerpts (in bold letters); these tittles don't appear in the original article.

Paradigm Shift in Expectations

Even after an early-September drop, stocks in Standard & Poor's index of 400 industrial companies sold at three times book value on average, the highest level since World War II. By these yardsticks, it was time to run for cover. Yet few leave. Those who cash in their winnings are replaced by others with radically new perceptions of value and plenty of money to back up their convictions. These investors look beyond book value and earnings, taking their cues from takeovers, leveraged buyouts, recapitalisations, and other forms of corporate restructuring. What counts with the new breed is how a company's balance sheet can be rejiggered to raise shareholder value to undreamed-of levels. How much debt can the company carry? How much cash can it throw off? How many divisions can be surgically removed and resold for a bundle? Do these folks know what they are doing? So far, despite that sharp drop in the Dow shortly after the bull market entered its sixth year, the new doctrines, and the experts who espouse them, are looking great. The bulls have left cautious money managers choking on a cloud of dust. For the first time, some analysts and market watchers mention numbers they thought only their grandchildren would hear: 3500 on the Dow, even 4000. Just look at Japan, they say, where stocks sell at 77 times earnings. Now six times cash flow is considered cheap. And jeez, I don't know what a cheap P/E multiple is anymore. It's all relative.

Perceptions

Where did the perception of added value come from? Keith Gollust, a founding member of Coniston Partners, says it stems from the ability to borrow money to buy companies ripe for breakup. ''For the foreseeable future,'' says Gollust, ''the value of equities is going to be very closely tied to the amount of liquidity in the debt markets.'' The prices offered, he adds, could move up or down: ''Valuations today depend upon the leveragability of the target company, and that's something that could change very quickly. It's very speculative. At the market's current levels, changes in the financial environment could have a dramatic impact on valuation.'' Translated, that means the wings could easily drop off stock prices. Money manager Soros sees nothing unusual in this precarious state of affairs. In his new book, The Alchemy of Finance, which examines the inner psychological workings of the stock market, Soros flatly rejects the idea that stock prices are fundamentally sound reflections of the underlying worth of companies. Stock market valuations, he says, are ''always distorted'' by the ongoing biases of investors, lenders, and regulators.

Reflexivity

THAT PUTS SOROS at the opposite pole from believers in the efficient-market hypothesis, which holds that stock prices quickly change to take account of all available news about the earnings prospects and general health of companies. He marches under the banner of what he calls ''the theory of reflexivity.'' The theory, which he applies to currency markets as well as stocks, holds that the prices investors pay ''are not merely passive reflections (of value); they are active ingredients in the act of valuation.'' One example Soros offers of how this theory plays out in the market: In the Sixties, the high prices of conglomerate stocks enabled companies to step up their buying sprees. This policy pushed prices even higher until the stocks collapsed. Examples of reflexivity abound these days too. A weak company with a low stock price has trouble raising money, and this drives the shares down further. Prices offered in takeover bids, on the other hand, can lead to a revaluation of a company's assets. That makes bankers willing to lend more to other bidders, which in turn can lead to still higher bids. Ultimately the process of valuing reaches its limits as prices go beyond all reason. Soros thinks that while the market is already unstable and overvalued, it has not yet reached the point of collapse. Indeed, it could yet move much higher. The upward march could stumble if some of the highly leveraged takeover deals being done today start going belly up.

Relative Valuations

Soros points to overly optimistic cash flow projections in many LBO plans he sees. ''There's no contingency for an economic downturn,'' he says. He also sees evidence that many of today's LBO participants who expect to sell off pieces of the company at high prices are counting on the bull market, rather than on an improvement in the company's fortunes, to bail them out. ''As a result of the bull market,'' he says, ''the expectation for higher values on asset sales has grown.'' So far, says Lambert of First Boston, ''that has been a good underlying assumption.'' Indeed, transaction values continue to beget higher transaction values. Says Winthrop Knowlton, the former chairman of Harper & Row who helped negotiate the sale to Murdoch's News Corp.: ''There is a ratchet effect here. As people pay more and more for companies -- higher multiples of book value or cash flow or whatever you want to use -- all the subsequent acquisitions in that industry are keyed to it. You look around at the prices of comparable companies in the industry, and they all go up.'' What Knowlton describes has been under way for some time. In 1985, when R.J. Reynolds Industries bought Nabisco Brands for $4.9 billion, or 3.2 times book value, the prices of all other food stocks quickly lurched up to reflect the upgraded valuations. Many of the big transactions that set the tune no longer bear any relation to the intrinsic value of the firm. Knowlton observes that while the price-to-book value and price-to-revenue multiples for publishing companies are rising on the coattails of new deals, the industry's real performance numbers are getting worse:

Replacement Value

YET BREAKUP VALUE still exerts a strong upward pull on stock prices. As the table below shows, several companies in the food industry sell for far more than can be justified by even a rosy estimate of the payoff from tighter, leaner management. The calculations were made by Alcar, which advises companies on how to raise the value of their shares and ward off raiders. But what if you took the company apart and sold it off in pieces? The breakup values used in the table are estimated by Alan Greditor, a food industry analyst at Drexel Burnham Lambert. Greditor's figures are closely watched by institutional investors who respect his record in spotting the untapped value in companies. Investors are still quite willing to accept the implied breakup value of companies as a guide to the true worth of stocks. Says Alfred Rappaport, chairman of Alcar: ''What investors are saying with recent stock prices is that they expect someone to realize the breakup value of those firms. If it's not current management, then it will be someone else.'' Rappaport advises his clients to accept these new valuations as a fact of life. He also teaches companies to focus not on earnings, an accounting concept, but on the cash flow -- retained earnings plus depreciation -- that actually pours into the coffers. And he urges many clients to leverage up by taking on more debt. These days, if the breakup value of a company far exceeds the market price, it can play the latest Wall Street gambit: a ''leveraged recap.'' It borrows tons of money and pays the shareholders a cash windfall. The fact that companies can do this -- or some raider can do it for them -- gets reflected in the stock price. Investors who navigate by breakup value are playing an increasingly dangerous game. Even if lenders remain willing to finance the takeovers that lead to breakups, other developments could weaken today's stock valuations.

Margin of Safety

An immutable dictum of investing is that you should strive to preserve the safety of your principal. There is no way to escape the ups and downs of the market. But what Benjamin Graham meant when he set down that rule of value investing was simply that the money invested should have a good prospect of surviving. Take a higher risk than that, Graham said, and you are moving into the realm of speculation, not investment. That stocks have moved up, up, and away from the fundamental measures of value does not mean they must tumble. Says Soros: ''Just because the market is overvalued does not mean it is not sustainable. If you want to know how much more overvalued American stocks can become, just look at Japan.'' Even after an adjustment is made for the peculiarities of Japanese accounting, Japanese stocks sell at P/Es of about 60. Soros thinks that those multiples rule out a happy landing for the Tokyo market: ''There's no turning back for the Tokyo market. The perception of value has become so extended, an orderly retreat seems impossible. There may be a crash coming.''

To view this post in your browser or to share it click Are Stocks too High.