Dear Friends and Music Lovers,

This post explores the differences in the way people thought about music (and the arts) in the 18th century compared to the 19th and later centuries. Neither way is better or more correct than the other, but a deeper appreciation of 18th-century music can come with an understanding of the motivations and ideals of 18th-century musicians.

In Western music today, performance is usually conceived as an interpretive art. Shai Burstyn, in an article in the journal Early Music titled ‘In quest of the period ear’, writes that underpinning this concept is the idea of a ‘communication triangle’, a division of labour whereby

This post explores the differences in the way people thought about music (and the arts) in the 18th century compared to the 19th and later centuries. Neither way is better or more correct than the other, but a deeper appreciation of 18th-century music can come with an understanding of the motivations and ideals of 18th-century musicians.

In Western music today, performance is usually conceived as an interpretive art. Shai Burstyn, in an article in the journal Early Music titled ‘In quest of the period ear’, writes that underpinning this concept is the idea of a ‘communication triangle’, a division of labour whereby

composers create musical works and notate them in scores from which performers perform [that is, interpret] for the edification and pleasure of listeners.

This deeply entrenched view reflects the ‘romantic glorification of the inspired composer’, who is seen as the ‘creator of original musical edifices’.

This way of thinking dates back to 19th-century Romanticism and is still prevalent today.

Bruce Haynes, in The End of Early Music: A Period Performer’s History of Music, contrasts 16th, 17th and 18th-century music, which he calls Rhetorical music, with music written in the 19th century and later, which he calls Canonic music.

Rhetorical music had as its main aim to evoke and provoke emotions—the Affections, or Passions—that were shared by everyone, audience and performers alike.

Canonic music, by contrast, was usually autobiographical in some sense, often describing an extreme experience of the artist-composer: cathartic or enlightening, but above all solitary and individual.

Several revolutions took place at end of 18th century and into the 19th century:

- Industrial Revolution (c.1760–1840)

- French Revolution (began 1789)

- Romantic Revolution (Romanticism)

These revolutions led to changes in ideals and ways of thinking. There were paradigm shifts in aesthetics and other areas.

Before these revolutions music and the arts were based on values and practices that seem fundamentally different to those we today call ‘modern‘. We take our modern ideas for granted or as givens. Not only do we assume our way of thinking applies universally but also that it is somehow better or superior.

So the 19th century has created a wide gap between us today and the 18th century. The differences are often difficult to appreciate or even to see.

---

To illustrate the point, here are two contrasting paintings produced about 100 years apart.

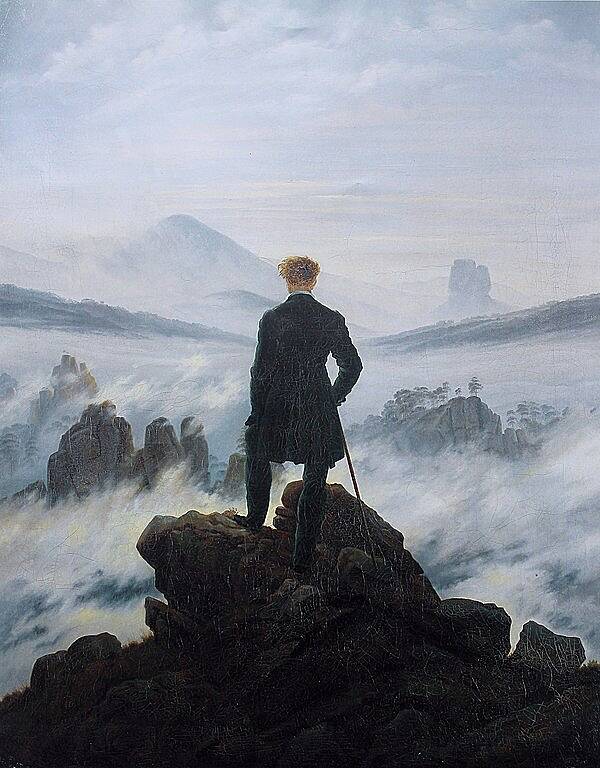

Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) was a quintessential Romantic landscape painter. Here is his Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (c.1818).

Historian John Lewis Gaddis describes this painting as leaving a contradictory impression, ‘suggesting at once mastery over a landscape and the insignificance of the individual within it. We see no face, so it's impossible to know whether the prospect facing the young man is exhilarating, or terrifying, or both.’

Themes: wild nature (chaos) | isolation (man against nature) | turmoil | cold

---

Here is an early 18th-century painting by Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721) —Les Deux Cousines (c.1716)

Three elegantly dressed figures are near a pond in beautifully tended park or gardens.

The painting embodies galant ideals of refinement, elegance, restraint, delicacy and propriety.

Themes: tamed nature (order) | shared intimacy | melancholy (?) contrasted with joyful love | serenity | warmth

---

One difference in the way people thought in the 18th century is that musicians (and other artists) saw themselves as craftworkers. Even Bach. They produced works of art for specific occasions or audiences. They were creating for their present and had no concept of creating something for posterity.

They strove to perfect their craft (skill) for the betterment of society. A strong motivation was the desire to communicate directly with the audience in front of them, to move them and persuade them, to educate and entertain them. To share with them. 18th-century artists were greatly influenced by the humanist philosophy of the ancient Greeks and Romans.

As a performer of 18th-century music I feel I need to take all this into serious consideration when I perform this music. I wrote about my approach in a previous post:

What is Historically Enlightened Performance?

To conclude I’d like to share a few quotes that I find instructive and worth reflecting on.

The first are from Bruce Haynes (quoted above):

We don’t think about it much, but in fact those old pieces were not written for us. Nobody back then knew what we would be like, what kinds of instruments we would be playing, or what we would expect from our music. In fact, they didn’t even know we would be playing their pieces.

And some more about the differences between Rhetorical and Canonic music:

Rhetorical music was temporary, like today’s films—appreciated, then forgotten—Canonic music was eternal and enduring. Rhetorical music was transient, disposable, its repertoire constantly changing. Canonic music was by definition stable, repeatable, and orthodox.

Robert Gjerdingen has written a fascinating book titled Music in the Galant Style. He explains that the word galant was

much used in the eighteenth century. It referred broadly to a collection of traits, attitudes, and manners associated with the cultured nobility.

He gives some insights into the life of a composer in the 18th century:

The composer of galant music, rather than being a struggling artist alone against the world, was more like a prosperous civil servant. He typically had the title chapel master (Ger., Kapellmeister; It., maestro di capella) and managed an aristocrat’s sacred and secular musical enterprises. He worried less about the meaning of art and more about whether his second violin player would be sober enough to play for Sunday Mass. The galant composer necessarily worked in the here and now.

…

In short, the galant composer lived the life of a musical craftsman, of an artisan who produced a large quantity of music for immediate consumption, managed its performance and performers, and evaluated its reception with a view toward keeping up with fashion.

---

Lucinda Moon and I have recorded music by some of the 18th century’s finest musical craftworkers. They were household names in their day and their music can still speak to us today. You can listen to a few tracks by following these links:

Quantz – Flute Concertos

Telemann – Melodious Canons and Fantasias

Boismortier – Six Sonates

Quantz – Sei Duetti

---

If you have any questions, thoughts or suggestions, you can contact me directly at dikmans@hey.com

Best wishes,

Greg Dikmans (Elysium Ensemble)

---

Email: dikmans@hey.com

Blog: https://world.hey.com/dikmans

Elysium Ensemble website: http://elysiumensemble.com

---

Related Posts

What is Historically Enlightened Performance?