Note: I’ve translated this article into Spanish on November 20th, 2025. Because this is a long read, you can find the article in the “Desde mi terminal” newsletter.

Imagine this: you're working hard in your tech company, perhaps building a cool new feature or keeping the infrastructure humming, and then word comes down that your company is being acquired, not by another tech giant but by a private equity firm.

Imagine this: you're working hard in your tech company, perhaps building a cool new feature or keeping the infrastructure humming, and then word comes down that your company is being acquired, not by another tech giant but by a private equity firm.

This can feel like a sudden shift if you're like many, perhaps raising more questions than answers. What exactly is private equity (PE), what does a buyout mean, and what might happen next for the company and you?

Let me share my experiences, alongside insights from others who have been through this transition, to help clarify this new landscape.

What exactly is Private Equity?

At its core, private equity involves investment companies buying entire businesses, often taking them private if they were previously publicly traded.

Their main objective is to increase the company's value, typically over five to seven years, and then sell it for a profit.

Unlike venture capital firms that fund young startups, PE firms target more mature companies. A standard method is a Leveraged Buyout (LBO), which uses a large portion of borrowed money (debt) alongside equity to fund the acquisition. Think of it like a mortgage: the firm puts down equity, and a loan covers the rest, secured by the company's assets and future cash flows.

While this approach can amplify returns, it also adds risk, since the company must repay the loans regardless of market conditions.

Why Tech? Why Saas?

PE firms love Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) because these businesses often have:

- High gross margins

- Predictable, recurring revenue streams

- Low capital expenditure once scaled

These traits make them resilient and great at generating cash. A stable SaaS company with loyal customers is an ideal LBO target.

Recent market dynamics

Over the past few years, broader macroeconomic shifts have reshaped the private equity landscape, particularly in tech. The easy-money era that fueled sky-high valuations gave way to inflation concerns, rising interest rates, and a renewed focus on fundamentals. This reset created a unique environment where PE firms saw opportunity in companies struggling to adapt. Here’s how that played out:

Over the past few years, broader macroeconomic shifts have reshaped the private equity landscape, particularly in tech. The easy-money era that fueled sky-high valuations gave way to inflation concerns, rising interest rates, and a renewed focus on fundamentals. This reset created a unique environment where PE firms saw opportunity in companies struggling to adapt. Here’s how that played out:

- ZIRP-era boom and bust: Tech valuations peaked around 2020–2021 due to the zero-interest-rate policy (ZIRP), then fell sharply as markets refocused on profitability.

- Buying opportunity: PE firms moved in to acquire undervalued assets, especially companies struggling to shift to capital efficiency.

- Profitability focus: PE firms prioritize efficiency and profitability over rapid growth.

- More extended hold periods: With IPOs tougher in 2022–2025, exits have been delayed, leading to longer ownership timelines.

The PE Playbook: How value is created

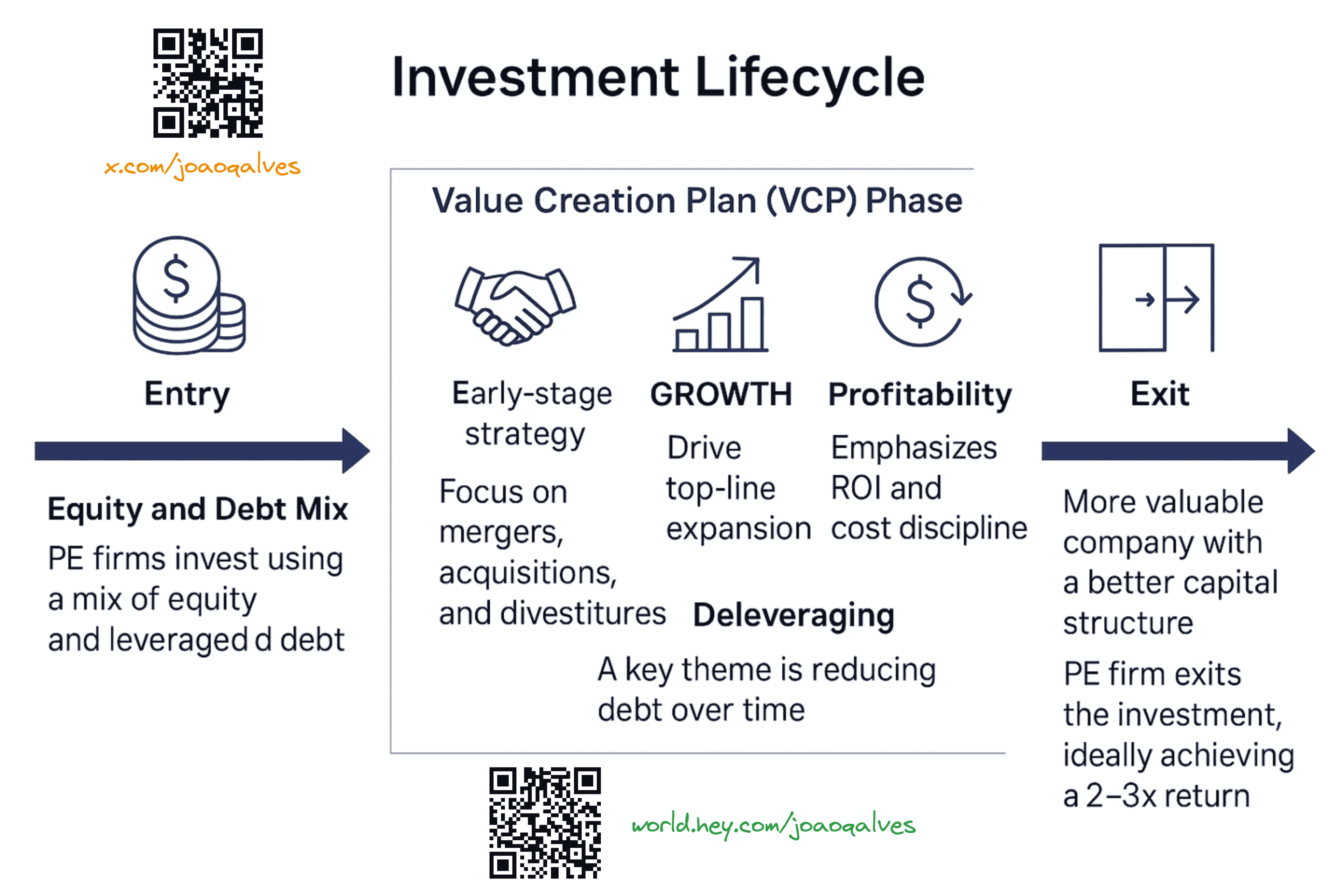

After acquisition, PE firms implement a Value Creation Plan (VCP) that typically includes:

- Debt paydown (deleveraging): using company cash flow to reduce acquisition debt.

- Operational improvements: cutting costs and improving profitability.

- Multiple expansion: selling the company at a higher earnings or revenue multiple.

There are a few common changes or signals you might see.

Cost cutting

Private equity firms almost always begin with a round of cost-cutting. This typically includes:

- Layoffs, often in the range of 10–30%, particularly in overlapping or non-essential departments. For instance, after Thoma Bravo acquired Anaplan for over $10 billion in 2022, more than 300 employees were laid off within a year.

- Discretionary spending cuts include reduced travel, entertainment, vendor spending, and budgetary tightening across teams.

- Office consolidations or transitions to remote-first operations to reduce real estate costs.

New leadership, with a focus on three key roles

After a private equity buyout, one of the earliest and most visible shifts is often leadership and organizational alignment. PE-owned boards may replace existing leadership or give them narrower mandates, especially if they are seen as too "growth-first," lack operational discipline, or are culturally misaligned with the PE firm's priorities. In particular, three roles are almost always scrutinized:

- The CEO is often the first role reviewed because they set the company's strategic direction and cultural tone. In many cases, CEOs coming from a venture-backed or "growth at all costs" environment may not be well-suited to lead in a PE-owned context, where value creation is tied more to free cash flow, operational efficiency, and exit planning. If a CEO resists a shift from rapid expansion to profit-driven scaling, or lacks experience leading through that kind of transition, PE firms may replace them with someone with a proven track record of executing turnaround strategies or successful exits. PEs expect the new CEO to lead urgently, drive accountability, and deliver against a well-defined value creation plan.

- The CFO becomes a pivotal figure under PE ownership, responsible for financial oversight and managing the company's ability to generate and retain cash. While earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) remains an important benchmark, PE firms prioritize free cash flow (FCF) as the actual performance measure since it is the cash that services debt and enables reinvestment. A CFO without strong experience in forecasting, liquidity planning, working capital management, or debt covenant navigation may be replaced with someone from a private equity, corporate finance, or investment banking background. The ideal CFO under PE can build clear dashboards, track return on investment (ROI) by segment, and help optimize capital structure to maximize returns.

- The Chief Human Resources Officer (CHRO) plays a critical role in enabling the organizational and cultural transformation that PE firms require. Often underemphasized in earlier-stage companies, this role becomes essential during post-acquisition transitions. The CEO/board typically tasks the CHRO with executing cost-cutting measures such as reorganizations or layoffs and redesigning compensation structures to align incentives with new financial KPIs. They also help shift the culture toward high performance, accountability, and transparency. CHROs often implement clearer performance management frameworks and career progression tied to business outcomes. A CHRO focusing more on long-term culture building or employee experience at the expense of operational alignment may be seen as a poor fit for the PE stage.

New KPIs

KPI focus shifts from growth metrics (like Monthly Active Users or Revenue Growth Rate) to profitability indicators like:

- Gross margin

- EBITDA

- Customer Lifetime Value (LTV)

- Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) payback period

- Rule of 40 (Revenue growth % + Profit margin % >= 40)

You can expect frequent reporting cycles and dashboarding around these metrics, with performance tied to bonus or equity incentives.

Price and revenue optimization

PE firms often believe companies are undercharging or leaving money on the table. With a focus on increasing revenue without increasing customer acquisition costs, PE firms encourage:

- Price increases across key products or services, sometimes subtly implemented with:

- Fewer discounts or promotions

- Annual contracts replacing monthly billing

- Price hikes bundled with "value-add" features (e.g., "you pay more but you also get more").

- Upselling to higher tiers or more feature-rich plans

- Cross-selling complementary products or services from within the portfolio or via bundled offerings

- Sales and customer success teams are often given new incentives and quotas tied to wallet expansion

Product rationalization

Research and Development (R&D) spending typically comes under the microscope post-acquisition. Management teams:

- Often cut experimental or long-horizon projects, especially those with unclear ROI or distant commercialization timelines.

- Reallocate investment to high-margin, proven products with known customer demand.

- Shift roadmaps from innovation to stabilization, focusing on performance, reliability, and monetization.

While this boosts profitability, it can slow innovation and lead to internal frustration for product and engineering teams used to a more experimental environment.

The hard truth: Cash flow > EBITDA

While EBITDA is a widely used metric to understand a company's financials, free cash flow (FCF) is arguably more important for private equity firms because it reflects actual cash available to service debt, reinvest, or return to investors. Why do PEs love free cash flow?

- Debt Service: The company takes on substantial debt in a leveraged buyout. FCF is what repays that debt, not EBITDA. If a company has strong EBITDA but poor FCF (due to high capital expenditure [CapEx] or working capital needs), it may struggle to service loans

- Predictability: High-quality tech/SaaS companies often convert EBITDA to FCF at high rates due to low CapEx needs. That makes them ideal for leveraged deals and easier to manage under PE ownership.

- Valuation and exit planning: PE buyers and future acquirers (or IPO investors) often value companies based on FCF multiples, not just EBITDA, especially in mature companies where growth has slowed.

- Cash distributions/returns: FCF allows private equity owners to:

- Deleverage quickly.

- Pay themselves dividends (dividend recaps).

- Reinvest in bolt-on acquisitions.

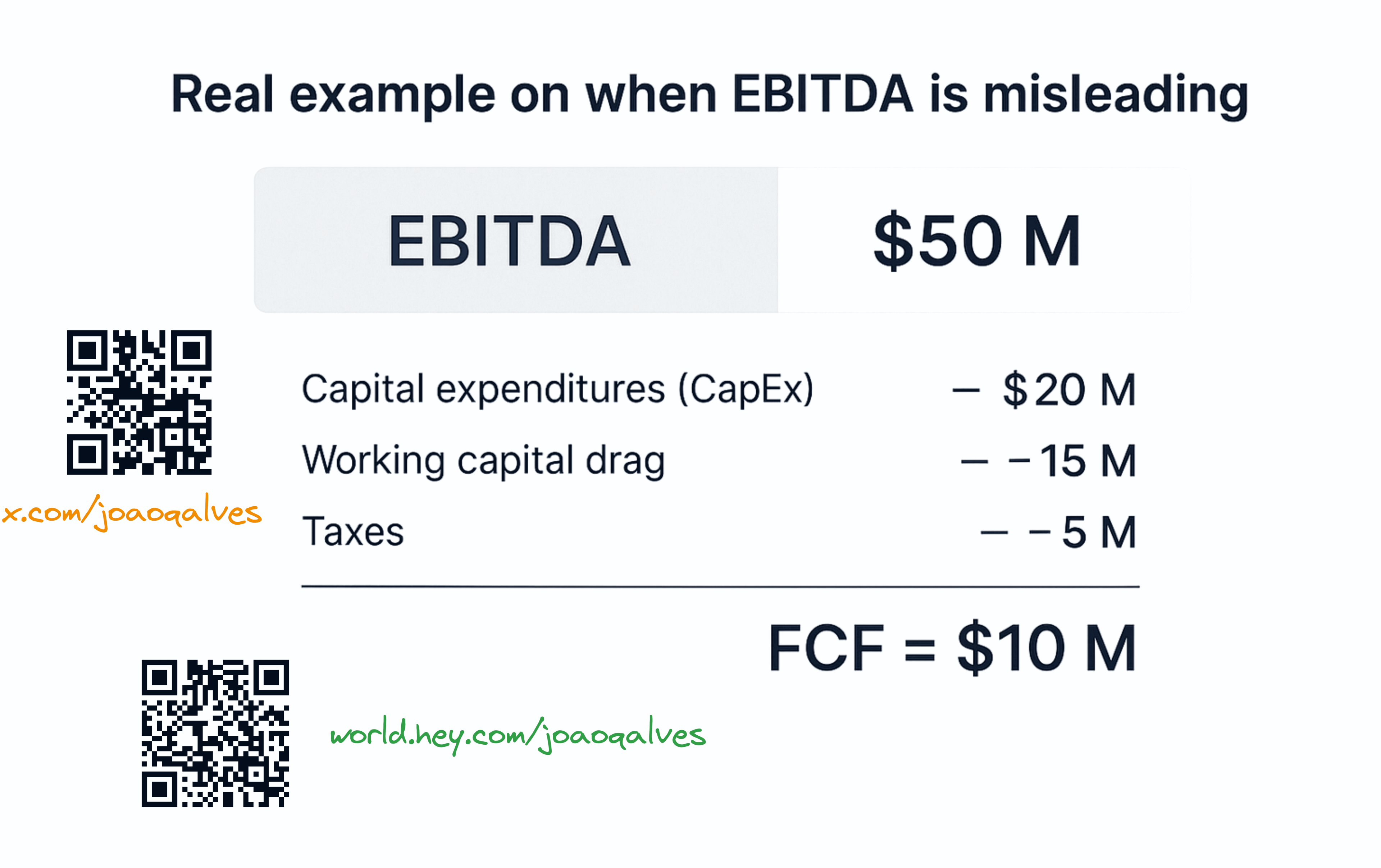

Real example of when EBITDA is misleading

Imagine a mid-sized SaaS company with a $50 million EBITDA. Sounds great, right? But now look at what's eating into that:

- Capital expenditures (CapEx): $20 million, because they run their own data centres and bought a ton of GPUs from NVIDIA.

- Working capital drag: $15 million. Sales are growing, but customers are paying late. Therefore, cash is tied up.

- Taxes: $5 million

So while the profit and loss statement (P&L) might look strong, the business is only throwing off $10M of usable cash. That's the number PE firms care about most. It determines whether debt gets paid off, whether bonuses get paid, and whether the exit plan stays on track. That is why, under PE ownership, the CFO and leadership team become laser-focused on FCF: cutting unnecessary spend, shortening payment cycles, and delaying CapEx unless it has a clear ROI. Because cash, not paper profit, is what keeps the deal alive.

What does it mean for me, as a tech professional?

1. Change is faster than ever

Once a PE firm takes over, decisions that used to take months may now take days or weeks. Speed is part of the playbook: the new owners quickly implement org restructures, re-prioritizations, and budget shifts to hit value creation targets. You may find:

- Projects were canceled or accelerated with little notice.

- Reorgs that change your manager or team structure overnight.

- Roles are evolving to match new priorities (e.g., shifting from R&D to product monetization).

Tip: anchor yourself to initiatives aligned with profitability, customer retention, or core product success. You'll be in a stronger spot if you lead or contribute to projects that generate revenue or reduce costs.

2. Operational discipline

The cultural shift can feel jarring if you're used to a "move fast and break things" environment. PE firms typically instill a more structured, ROI-driven operating model:

- Budget approvals may now require detailed business cases and ROI models.

- Finance people may ask every team to justify their expenses, headcount, or initiatives.

- Tools like OKRs or KPI dashboards become standard, with a clear link between individual contributions and company-level metrics.

The upside? Less chaos and clearer priorities. The downside? Less tolerance for ambiguity or experimentation without results.

3. Career and compensation

Your total compensation package may shift:

- Career progression may become more structured and tighter. Promotions are often more directly tied to measurable business impact. Advancement may slow if you can't connect your role to cost savings, revenue growth, or efficiency.

- Performance reviews also tend to become more rigorous, with regular check-ins against specific KPIs and a higher bar for continued advancement.

- You'll get exposure to rigorous business fundamentals, from cash flow modeling to unit economics to board-level performance reviews.

- Many PE firms bring in seasoned operators, advisors, and board members, offering mentorship and networking opportunities.

- Base pay might remain good, but variable compensation (bonuses, equity) may now be tied to EBITDA, Free Cash Flow, or other financial milestones.

- Some employees may be granted new equity, typically under long-term incentive plans that align with the PE firm's exit strategy (e.g., sale or IPO).

This can feel like a significant cultural shift, especially if you came from a high-growth startup with broad roles and informal promotion paths. That said, top performers tend to thrive under this system. In particular, those who enjoy accountability, clarity, and a tangible connection to company performance.

The PE phase can be professionally and financially rewarding if you're analytically minded, execution-driven, and adaptable.

Final Thoughts

Private equity's growing presence in tech marks a new era. The days of free capital are over. PE firms are betting on undervalued companies and using financial and operational rigor to extract value.

Understanding this shift from high growth to high efficiency and staying adaptable can help you navigate the changes ahead. Have you experienced a PE buyout? How did it go?

— João

I’m building RotaHog, a lightweight tool for managing team rotation schedules (on-call, support shifts, release duties, etc.). Try it if you're tired of hacking spreadsheets or Slack threads together. I’d love your feedback!

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to the newsletter and buying me a coffee.

— João

I’m building RotaHog, a lightweight tool for managing team rotation schedules (on-call, support shifts, release duties, etc.). Try it if you're tired of hacking spreadsheets or Slack threads together. I’d love your feedback!

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to the newsletter and buying me a coffee.