The software development industry during the 2010–2020 decade created roles such as Engineering Manager (EM) and Tech Lead (TL). People had already been using one or the other, but during that decade, most companies adopted them. While they vary by company, they share common elements.

Note: this article is a translation from the original “Señales de un buen Tech Lead”, in Spanish. However, this post is slightly different and contains a short “Frequently Asked Questions” section.

What is a Tech Lead? How is it different from an EM?

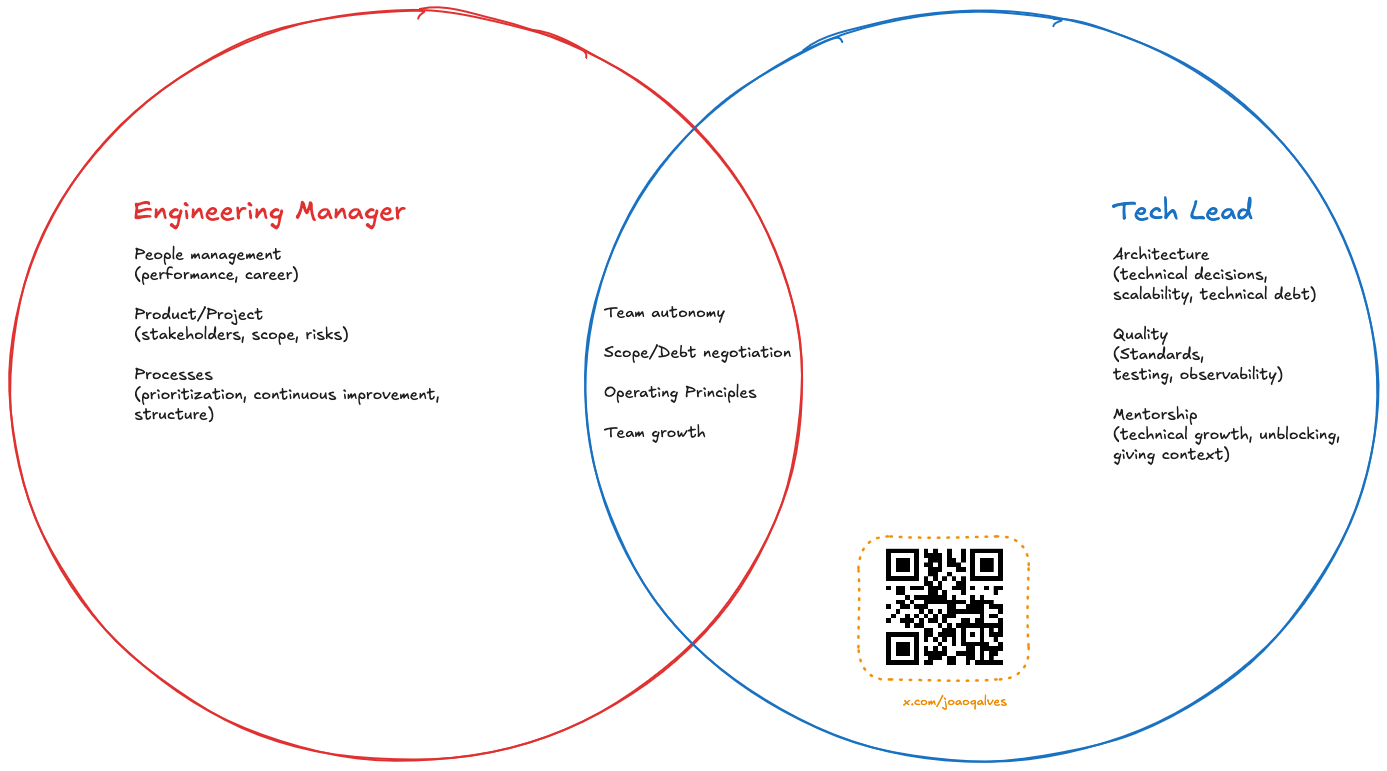

Many people already have a clear idea, but here is my view of these two roles:

Engineering Manager: responsible for the team. Most of the work falls into three management areas:

- People: ensuring people perform well and everything that comes with it (performance reviews, career development, etc.).

- Product/project: ensuring sustainable delivery of required features (stakeholder management, expectations, scope negotiation, de-risking, etc).

- Processes: how do you prioritize bugs vs new features? How do you decide what to work on this week? How do you run continuous improvement? The point is not to add processes ad nauseam. It is to find the balance needed for the team to operate independently — ideally without the EM — and to add some structure to natural chaos.

Tech Lead: responsible for the technical direction of the team. The focus is on three areas:

- Architecture: define key technical decisions, review proposals, ensure solutions scale, and ensure that technical debt is manageable. Most of all, ensure debt is intentional, not accidental.

- Quality: maintain high standards across code, reviews, testing, and observability. It is not about doing everything. It is about raising the bar for the team.

- Mentorship: help engineers grow, unblock complex problems, share context, and enable better technical decisions across the team.

As you can see, these roles are very different and require distinct approaches. One person may hold both roles. In a way, the end of the zero-interest-rate era (ZIRP) and the focus on efficiency pushed EMs back toward a more hands-on approach.

Note: I excluded the Product Manager role from the diagram, since that is not the focus of today’s article. Your real world is probably more complex.

Operating models

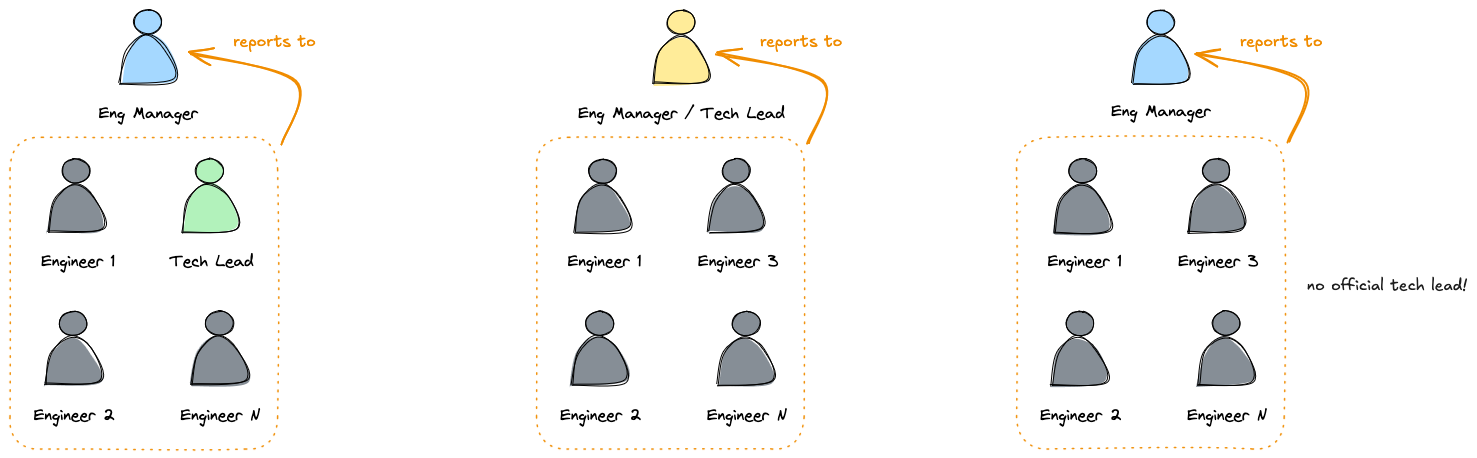

- EM and TL are official roles held by two different people.

- EM and TL are official roles held by the same person.

- EM is the only official role, and engineers are expected to lead technical initiatives without holding that title. This implicitly means the EM ensures the team is covered across all three TL areas.

There are other setups, but these are the most common. We will explore a model with an EM and a TL reporting to them. Across the models, differences are not significant, though the details vary. In the EM+TL case, the director must define what “good” looks like. If there is no formal TL, the EM must understand which areas require coverage and evaluate engineers across their key dimensions.

Today, we will not talk about Staff or Principal Engineers who operate across multiple teams. That will be

for another article.

---

👋 Hi, João here. This is the opening post of a series designed for Tech Leads and Engineering Managers who want to lead with greater clarity and intention.

I’m currently writing “The Tech Lead Handbook”, scheduled for release in H1 2026. The ideas in this series will form its core.

If you want to join the waitlist, you’ll get a 25% launch discount.

---

How do I know if a TL is doing a good job?

Across the three pillars above, one constant is that the TL is expected to have a multiplier effect on the team. Effectively, it means the TL should not become a bottleneck. The TL should help the team become autonomous. If the team still relies on the TL for decisions after a reasonable adaptation period, it indicates that the way of working needs adjustment and that the TL is likely not fulfilling the role.

Still, this can sound abstract. In practice, a good TL looks a lot like a Staff+ engineer. Someone who goes beyond task execution and focuses on ambiguous or structural problems. Someone who works with clarity, good judgment, and range. Someone who provides technical direction, reduces ambiguity, and pushes the team toward decisions that serve the whole system, not just one area.

A TL defines the what and the how when needed. But also creates the conditions for others to do the same. They identify risks, simplify open problems, prevent scope creep, and align technical work with product goals. And, above all, a TL generates speed: with clear operating principles, with written artifacts that create space for reflection (Requests for Comments, proofs of concept, design proposals), and with decisions that others can understand and carry on without depending on the TL.

We can anchor this in concrete signals across the three pillars: architecture, technical scope, and operating principles.

Architecture

Helpful behaviors

- Use Requests for Comments (RFCs) or other short documents to structure technical debates and force clarity: problem, alternatives, trade-offs, and decision.

- Notice when a discussion goes on without progress and propose a proof of concept (PoC) or a small experiment to validate assumptions.

- Make it explicit when decisions create technical debt and explain why it is acceptable at that moment.

- Involve the team in key decisions so everyone understands the reasoning and can make sound judgments.

Behaviors that slow things down

- Making improvised decisions in chats or hallways with no written record.

- Extending meetings endlessly with no clear synthesis or next step.

- Designing solutions without validating risks or assumptions with a prototype.

- Being the only person who knows “how everything works” and becoming the keeper of knowledge.

Technical scope

Helpful behaviors

- Actively negotiate with the EM and Product Manager on the balance between technical debt and value delivery. Understand business constraints and defend that quality is the only way to maintain mid-term speed.

- Detect technical scope creep: extra complexity, bonus non-functional requirements, or decisions that enlarge the system without real value.

- Simplify solutions by proposing reasonable technical phases: first, something that works, then something that scales. In other words, identify the minimum viable change.

- Regularly review whether the current design still matches the problem. Remove parts that no longer help.

- Surface dependencies or technical risks can delay the team if not addressed early.

Behaviors that slow things down

- Adding technical requirements “just in case” and increasing delivery cost for no reason.

- Overdesigning systems that could be simpler.

- Ignoring signs that the team is taking on something too big for the available time.

Operating principles and team velocity

Helpful behaviors

- Define written operating principles that serve as a compass: what we prioritize, what we avoid, and what “good” means for the team.

- Influence without authority: persuade through reasoning and vision, not hierarchy. Seek consensus when possible, and use “disagree and commit” when needed to unblock the team.

- Use these principles to accelerate decision-making and reduce dependence on the TL.

- Review principles with the team regularly and adapt them to the product reality.

- Promote consistent decisions so the team gains confidence and moves fast without asking for permission.

Behaviors that slow things down

- Making ad hoc decisions that change every week and confuse the team.

- Avoiding hard conversations due to fear of conflict (artificial harmony) or letting trivial debates (bikeshedding) stall the team.

- Keeping personal criteria hidden and allowing each person to optimize based on their own preferences, with no shared technical direction.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do you think the role changes if the EM and TL are the same person?

When the EM is also the TL, the model can work, but it changes a few things.

- Evaluation gets harder. The Senior EM or Director has less visibility into day-to-day technical work and therefore needs more context. That means more managing up from the EM/TL, and regular skip-levels so leadership can gain a clear sense of how the team operates.

- Delegation becomes essential. One person cannot manage people, projects, and technical direction without becoming a bottleneck. The solution is to develop “champions” within the team for areas such as quality, security, and architecture, and to spread technical ownership.

If it works well, you should see three signals: the team maintains its pace, decisions don’t centralize in one person, and leadership has clarity about what’s happening. If those signs are missing, the model needs more structure around them.

---

I like the "keep personal criteria hidden" part, but there is always debate between imposing and convincing. Many times, even if we believe something is the right choice, people won’t like it for various reasons, and then you enter the territory of imposing things.

When something feels like “imposing”, it’s usually because the principles are not explicit, or because they weren’t co-created. That’s why I’d approach it from two angles:

- Make the principles explicit. If the team agrees to “we prioritize X over Y” or to use specific standards, enforcing those standards isn’t burdensome. It’s consistency. Principles reduce subjective debates and prevent each person from optimizing in their own direction.

- Reframe debates around outcomes, not preferences. Questions like “Are we solving the real problem?” and “Is this the smallest step that moves us forward?” help shift the conversation away from taste and toward impact.

When there’s disagreement on approach, run a small PoC with clear criteria. A one-day experiment is cheaper than a week of arguing, and data removes most of the emotion.

And yes, not every decision will please everyone. But in the long run, principled leadership with clear boundaries creates more autonomy, not less. Teams mature faster when decisions are coherent and aligned, rather than driven by who argues the loudest.

The real impact of a TL

At its core, the challenge of a Tech Lead is not about knowing more than everyone else. It is about creating an environment where the team can think better, decide better, and move better. Every organization and every team needs something different, so there is no universal recipe.

However, we can observe how work flows, how decisions are distributed, and how the team’s autonomy evolves. That is where you see the real impact of a TL. And maybe the question each TL should ask is not “Am I doing this well?” but “Is the team depending less on me each month?” That answer is usually more honest and valuable than any checklist.

---

---

🎁 Want to put this into practice with your team tomorrow? A gift for subscribers!

Friction between EMs and TLs often comes from unspoken expectations. To close that gap, I created a FREE alignment toolkit with three practical tools:

- For Tech Leads: a self-assessment “semaphore” to fight impostor syndrome and know exactly where you add value (and where you are burning out).

- For Engineering Managers: an evaluation “semaphore” to give objective feedback based on behaviors, not gut feelings.

- For the team: an operating principles template to stop debating the same decisions every week.

Subscribe, complete this form, and I’ll send you the kit so you can move from intention to action. It is FREE!

— João